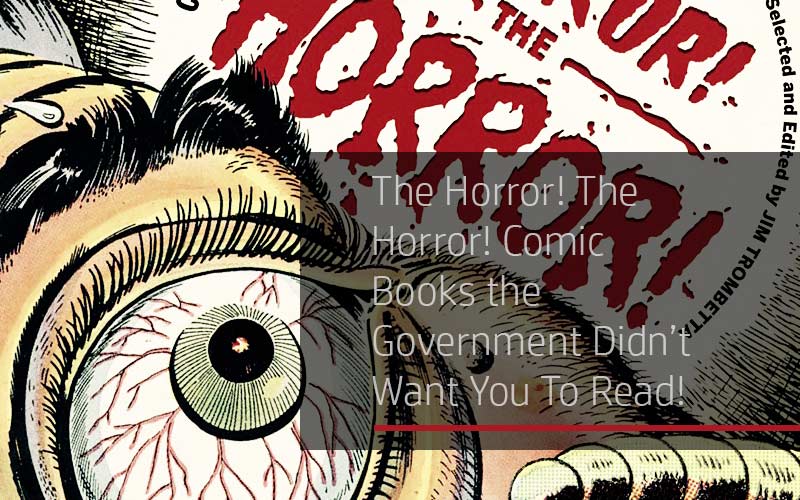

The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You To Read!

When the Comics Magazine Association of America established the Comics Code in 1954, not only was salacious, suggestive, violent and horrific content banished from comic books but an entire industry was decimated. This self regulating body, which operated under political and commercial interests, came into effect following the widespread panic that America’s youth were on a crash course to delinquency on account of comic books. Comic books were not particularly new, but certain themes in the comic books were, and they proved enormously popular with young readers. Titles such as Chamber of Chills, Horrific, Startling Terror, Black Cat and Worlds of Fear were devoted to supernatural and horror themes, while, beneath equally spectacular and tasteless cover art, Crime Does Not Pay, Law Breakers Suspense Stories, Law-Crime and Crimes by Women covered the gun toting mobsters and their leggy molls.

When the Comics Magazine Association of America established the Comics Code in 1954, not only was salacious, suggestive, violent and horrific content banished from comic books but an entire industry was decimated. This self regulating body, which operated under political and commercial interests, came into effect following the widespread panic that America’s youth were on a crash course to delinquency on account of comic books. Comic books were not particularly new, but certain themes in the comic books were, and they proved enormously popular with young readers. Titles such as Chamber of Chills, Horrific, Startling Terror, Black Cat and Worlds of Fear were devoted to supernatural and horror themes, while, beneath equally spectacular and tasteless cover art, Crime Does Not Pay, Law Breakers Suspense Stories, Law-Crime and Crimes by Women covered the gun toting mobsters and their leggy molls.

Fired up by the media, America panicked and communities all over the country reacted by holding comic book bonfires, encouraging their children to give up their comics and burn them. It was a scene no intelligent society should tolerate, but the book burning pyres of Germany a few years earlier had clearly dissipated with the baying for fresh blood.

The comic companies that produced horror and crime titles—which was most of them—had turned the novelty of the comic book into a nationwide commercial phenomenon, and the comics themselves a major new art form, as unique to American culture as jazz music. And then, overnight, all but a handful of the comics and publishers were gone.

Lately there has been a resurgence of interest in comic books of the 1950s, specifically the horror and crime comics that for so long were the ugly progeny of the comic book industry. This resurgence coincides with the growth of the so-called ‘graphic novel’ as a legitimate literary form, but is actually more a reaction to it than a product of it: Legitimate and good art is rarely interesting, little wonder that some people should seek out other forms of it.

EC Comics also helped to shape this resurgence; their key titles Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror and The Haunt of Fear, and highly talented team of artists, have come to epitomise what fifties horror comics are all about. EC publisher Bill Gaines even represented the maligned medium during the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency in spring 1954. (He belly-flopped.) But EC is not even half of the story, simply one publisher among the many that turned out hundreds of comic titles every month. Ace, Prize, Harvey, Avon, ACG, Ajax-Farrell, Star, Fawcett, Ziff-Davis, Atlas and Story are but a few of the other publishers.

Until recently, the greater history of the comic book was lost amid the frequent reprints of EC titles, the many authoritative books dedicated to EC, and the prestige of EC movie and television offshoots. Other comic publishers of the day were largely exiled from comics history or simply regarded as lowly rip-off merchants, their stories considered to be badly executed facsimiles of the EC style.

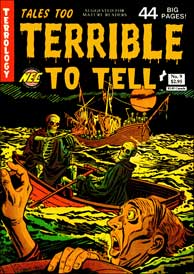

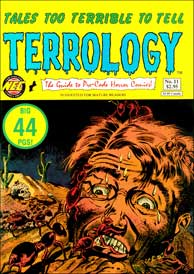

Having exhausted EC through the reprints, it was a surprise to discover the many other companies churning out like-minded material in the fifties. My education on the subject, and daresay that of many other people, too, was a series of magazines called Tales Too Terrible To Tell (aka Terrology).

Published by NEC, Tales Too Terrible To Tell first appeared in 1989/1990 and, for eleven issues, sought to redress the EC monopoly by reprinting horror strips published by these other companies. The magazine was relatively low budget, reproducing strips that were originally in colour on b&w pulp stock, but this in many ways suited the humble content and heightened its appeal. Along with the reprints, each issue carried an informed history of pre-code comics and publishers that was written by editor George Suarez. Tales Too Terrible To Tell was fresh information and an inspiration for future collectors.

Tales Too Terrible To Tell ran until 1993, when, along with its short-lived companion titles, Extinct! and Anti-Hitler Comics, the magazine folded without adieu. By this time, however, interest in pre-code horror and crime comics was buoyant enough for other works on the subject, such as Mike Benton’s lavish book series, History of Comics, published by Taylor in 1993. Volumes one and five cover horror and crime, and while this coverage includes some modern comics, the series is indebted to early titles.

At this juncture it’s fair to comment on another book, Martin Barker’s A Haunt of Fears, published by Pluto in 1984. It is possibly the first book devoted to the controversy surrounding comic books of the 1950s, albeit from a purely British perspective. It’s fitting that Barker should have written it; that same year, Barker edited The Video Nasties (also Pluto, 1984), the first book to examine the controversy over videos as it was raging in Britain at the time. Both the comics and video campaigns run a frightfully similar course, from a witch-hunt to a clampdown, by way of an ambiguous piece of legislation (a Comics Code and a Video Recording Act) that clears the playing field to the benefit of the bigger companies.

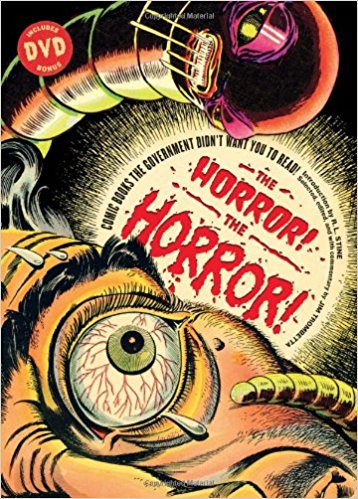

So we arrive at The Horror! The Horror! Comic Books the Government Didn’t Want You To Read! This hefty, oversized book uses isolated pages and panels from horror comics of the 1950s, along with a few key strips, to tell what might seem by now a familiar story. But author Jim Trombetta has an arresting take on it, one that readers will applaud and probably laugh at in equal measures.

Jim Trombetta is noted in the biographical blurb as a Shakespearean scholar, a reporter and editor for Crawdaddy, the Los Angeles Times, and other publications. He is also a writer on TV shows, including Miami Vice, The Flash and Star Trek. The blurb says nothing of him being a psychoanalyst, but in this book he acts as one, picking through old comic books with an analyst’s eye. This is more fun than it might sound, and it strikes some interesting chords.

The chapters are relatively short, with the text for each lasting no more than a page or two. The emphasis is on the artwork and strips, and in this respect the book’s design, by Jacob Covey, is every bit as important as the words of Trombetta. (The reproduction of comic strips in The Horror! The Horror! is top class: The stock is yellow for a decayed comic book look, and the colours and contrast muted.) Trombetta observes the typical concerns of an era living under the threat of nuclear Armageddon, and applies it to his discussion, but then his accent is on some unusual minutiae inherent in the comics, such as that of a disembodied leg that appears on one cover from 1953.

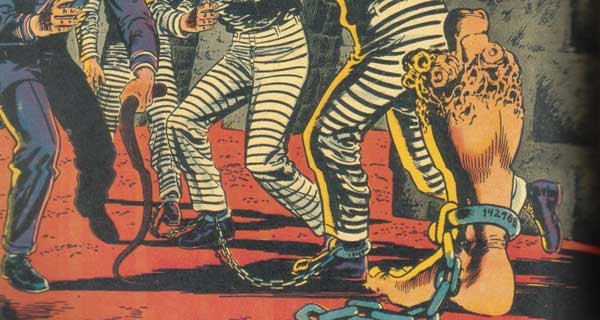

The cover in question, by Hi Fleishman, graces Dark Mysteries issue thirteen (August 1953), and it features in a chapter called Tom’s Leg. Fleishman’s artwork depicts a prison yard, where several inmates follow the startled gaze of a warden towards a dismembered leg standing in a corner. The rest of the body is missing. “It’s Tom’s leg,” exclaims the warden, “but he was executed last night!” Overseeing the macabre scene through the bars of a nearby cell is a skeleton.

Trombetta’s considerations are worthy of note. ‘The image invokes several horror myths,’ he writes,

crime and punishment, dismemberment, cannibalism, living dead—without establishing any real relationship between them. It is supersaturated with dream imagery that refuses to fit together, from Tom’s leg to the guard’s snakelike pissle to the skeleton on the right clutching the iron bars of the closet size cell…

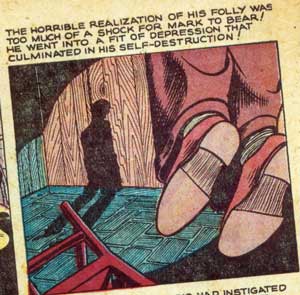

The fact that none of the above elements fit is key to the appeal of the pre-code comics, Trombetta determines. Tom’s leg is unadulterated nightmare, with no rhyme or reason. It’s a little silly, but that in itself is nightmarish. Trombetta goes on:

As with many horror comics covers, there is no coherent history that could have produced the event we see on Dark Mysteries number thirteen. Likewise, while the cover is genuinely ominous, it is hard to imagine what could possibly happen next. Perhaps the guard and prisoners will break into a dance routine from Jailhouse Rock…

Trombetta draws on literary theorist Northrop Frye in his lead to describing this cover, with references to iconic modes and whatnot. Comic artists of the 1950s were paid a lowly, standard fee. They were probably not overly aware and even less bothered by what they were conveying, outside the fact it was a job, and they were making horrible images for horror comics. Perhaps this itself is some kind of exorcism of the subconscious? In our more enlightened times, comics and comic characters require some semblance of a back story, and Tom’s leg would no doubt suffer a postmodern take that drives the reader forward on the pretext some sense will come of it all. Hi Fleishman does not offer any such comfort with Tom’s leg. It is what it is.

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress