How I First Encountered H. H. Holmes

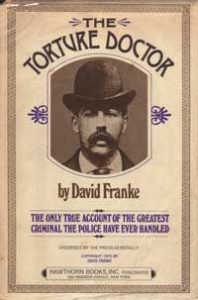

I first encountered the name H. H. Holmes courtesy of a book entitled The Torture Doctor: The Only True Account Of The Greatest Criminal The Police Have Ever Handled by David Franke (published in 1975 by Hawthorne, New York). The book was on sale at a book collector’s fair, which was in the exciting days before eBay. At £10 however, its price proved prohibitive and so I left it. Some years later, at another such collector’s fair, I encountered The Torture Doctor once again. This time I snapped it up, the title and subject matter—not to mention untrimmed pages and small press feel—having stayed with me and intrigued me since our first encounter.

I first encountered the name H. H. Holmes courtesy of a book entitled The Torture Doctor: The Only True Account Of The Greatest Criminal The Police Have Ever Handled by David Franke (published in 1975 by Hawthorne, New York). The book was on sale at a book collector’s fair, which was in the exciting days before eBay. At £10 however, its price proved prohibitive and so I left it. Some years later, at another such collector’s fair, I encountered The Torture Doctor once again. This time I snapped it up, the title and subject matter—not to mention untrimmed pages and small press feel—having stayed with me and intrigued me since our first encounter.

The story of H. H. Holmes is a strange one. So strange that at times it borders on the surreal, and so unfamiliar a case that for a while I was convinced H. H. Holmes was a complete fabrication on the part of author David Franke.

But he isn’t a fabrication.

Holmes was an entrepreneur and a swindler who, on May 7, 1896, was hanged for murder. In his jail cell, having initially confessed to killing twenty seven people, Holmes later retracted this statement and said he was guilty of only two deaths. In actuality Holmes murdered at least nine people, although an unofficial tally pegs the body count at around fifty with some reports even suggesting as many as 200 victims.

Amongst these victims were Dr Robert Leacock, a former schoolmate whom Holmes killed in 1886 for $40,000 in life insurance; Dr Russell who was bludgeoned during a rent dispute and whose corpse Holmes sold to a medical school, inaugurating Holmes’ side trade in selling the bodies or skeletons of his victims; Julia and Pearl Conner, mother and daughter killed on Christmas Day in 1891; Lizzie, a maid who was suffocated when Holmes feared she might run off with his janitor; Emeline Cigrand, stenographer and mistress suffocated on the day Holmes was supposed to marry her; the Williams sisters, after forcing Nannie Williams to sign over everything she owned; his sometime accomplice Benjamin F. Pitezel, burned alive for $10,000 in life insurance; Pitezel’s three children, poisoned, gassed, dismembered and burned, and numerous others.

One of the most bizarre aspects of an already bizarre case—one that saw the killer travelling up and down the US, casting an intricate web of deceit—is the “castle” that he built in Englewood, Chicago. The three storey edifice was a maze of secret chambers and passageways, chutes, trap doors, laboratories and corridors, housing a variety of torture chambers. Some of the rooms were air-tight and windowless, lined with iron plates or asbestos into which Holmes, from the comfort of his own suite, could pump noxious gas or flames. In the basement police discovered surgical instruments, a blood soaked dissecting table, vats of corrosive acid, a pit of quick lime, a furnace, and even a Medieval torture rack (which the physician Holmes tried to dismiss as his “elasticity determinator”).

Up until his arrest, only Holmes himself knew the full extent of the building’s many convolutions, thanks to the long succession of workmen he hired and fired during its construction, and who would only ever be allowed to view isolated aspects of the plans.

The “castle” sounds like a creation straight out of Edgar Allan Poe or de Sade. It was perfectly situated for the 1893 Chicago exposition, which brought many thousands of visitors to the city, and for whom Holmes was able to offer lodgings. Notably single young ladies…

Apart from several early cash-in books released in or around 1895, including Holmes’ Own Story—one of several ‘confessions’ written by Holmes—very little pertaining to the colourful and intriguing murderer had appeared prior to the publication of Franke’s The Torture Doctor. The case was luridly revisited in a 1954 edition of the true crime magazine Crime Case Book, while a pulp paperback printed in 1955, The Girls in Nightmare House, more resembled a horror movie tie-in than a document of fact.

There was a radio play based on the case broadcast by CBS as part of their Lights Out series of shows in August 1943, which was popular enough to find its way onto vinyl shortly afterwards.

Robert Bloch’s American Gothic, published in 1974, was a loose, fictionalised account of the Holmes case, and may have proved the inspiration for Franke, whose Torture Doctor appeared the following year.

In more recent years there has been a rekindled interest in Holmes courtesy of several works of fiction, including a return by Bloch in ‘Dr Holmes’ Murder Castle’—one of the stories in the anthology Tales of the Uncanny, published in 1983. To name but a few of the others: Allan Eckert’s The Scarlet Mansion (1985) is a highly regarded adaptation, Olivia Diamond presents the reader with a time-travelling Holmes in The Pluperfect Phantom (2001), and Eric Larson landed on the New York Times bestseller list with his The Devil in the White City (2003).

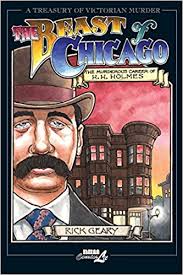

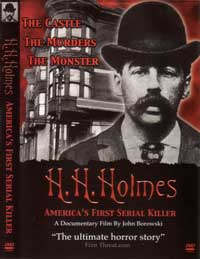

Factual documents of the case returned with Harold Schechter’s 1994 book Depraved. More recent is Rick Geary’s graphic novel, The Beast of Chicago, published in 2003 and, released the same year, a documentary film by John Borowski: H. H. Holmes: America’s First Serial Killer.

The subjects of this review, Geary’s book and Borowski’s film, while produced independent to one another and very different in their respective approach, may be regarded as unofficial companion pieces.

Rick Geary is a comic artist of some repute who has worked for such esteemed publications as National Lampoon, Mad, Rolling Stone, Heavy Metal, Disney Adventures and others. His series, A Treasury of Victorian Murder, published by NBM, has seen Geary adapt in graphic novel form such noted historical crime cases as Jack The Ripper, Mary Rogers and Lizzie Borden. The Beast of Chicago is the sixth volume in the series.

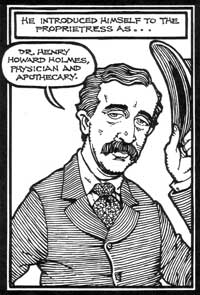

Geary’s artwork has a warm, engaging feel to it: very clean lines and good use of space. It is a style that on the surface would appear to be more suited to satire or humorous pieces, but somehow it lends itself perfectly to dark subjects such as those in this series. Not that Geary dwells on the many elements of graphic horror, preferring instead to imply such scenes or allow any carnage to fall just outside of the panel.

Geary’s artwork has a warm, engaging feel to it: very clean lines and good use of space. It is a style that on the surface would appear to be more suited to satire or humorous pieces, but somehow it lends itself perfectly to dark subjects such as those in this series. Not that Geary dwells on the many elements of graphic horror, preferring instead to imply such scenes or allow any carnage to fall just outside of the panel.

Geary packs plenty of information into his retelling of the Holmes story, bringing to it life and clarity. His interpretation of details drawn from old newspaper reports and staid courtroom drawings are brilliant to behold, while his rendition of the Castle’s mysterious second floor, with all its secret passageways and deadly rooms, is every inch as awesome as, say, Jack Kirby’s breakaway of the Baxter Building complex back in the classic Fantastic Four days.

It is not really a surprise to learn that Holmes’ Castle provided filmmaker John Borowski with the inspiration to make his documentary H. H. Holmes. A festival favourite and winner of several awards, the film is now available on DVD, a release limited to 1000 copies (a tastefully numbered Death Certificate insert denotes my copy to be number 799, signed by the filmmaker).

Director Borowski—who also produces and wrote the screenplay—has come up with an engaging film that nicely combines original newspaper reports, staged reconstructions and interviews with the likes of criminal profiler Thomas Cronin and Depraved author Harold Schechter. It would have been interesting to see an interview with Torture Doctor author David Franke, but I dare say he is nowhere to be found.

Three years in the making, the film has the attitude of being a true labour of love for Borowski, who has gone on to give lectures on the film, on Holmes and on true crime in general. He has also clearly spent much time, effort and money accumulating Holmes memorabilia—as a collector as much a researcher.

The narration in the film is rich, although in part does suffer from the type of sloganeering that news media and infotainment audiences have come to expect, describing the Holmes court case for instance as the “O. J. Simpson trial of the day”.

This minor gripe aside much interesting information is brought to light, such as criminal profiler Cronin noting that most serial killers don’t finish college, which makes the scholarly Holmes unique amongst serial killers. The film also places Holmes into a criminal-history perspective courtesy of Jack the Ripper, active at around the same time and whose own deeds would most certainly have reached Holmes from across the Atlantic, serving to fuel or inspire him.

Borowski’s film rightly posits H. H. Holmes as a folk figure, a national bogeyman, although I don’t necessarily agree with the sentiment that the “entire world will remember him”.

(Maybe this will all change if two unrelated Hollywood films on Holmes come about, given their respective connections to box office gold, Tom Cruise and Leonardo DiCaprio?)

Amongst the people credited in the film is Rick Geary, who—not unlike Holmes and Jack the Ripper—must have been working on his own retelling of the tale at around the same time as Borowski. One of the extras on the DVD shows unused art furnished by Geary for the film. The fact that this work was never used is a shame as it stands as a very eye catching piece indeed, markedly more arresting than the one-colour photo montage that actually graces the DVD.

The Beast of Chicago and H. H. Holmes: America’s First Serial Killer may not be the last word on the fascinating subject of HH Holmes—a man who claimed that his evil deeds were outwardly manifesting themselves and changing the shape of his face—but both are original and equally worthy of your time.

For more information on H. H. Holmes: America’s First Serial Killer, visit the website at http://hhholmesthefilm.com

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress