Social Darwinism, Dada and Tiki – The Confusing World of Boyd Rice

What’s the difference between a Nazi and a Satanist? A genuine question, that, rather than the opening salvo of the gag-you’re-least-likely-to-find-in-a-Christmas-cracker. And the answer (or one of them) is that they practice wholly different forms of anti-Semitism. The former (primarily) hates the Jewish race, the latter the Jewish moral and theological tradition. The two aversions, however, have often touched fingers, like God and Adam stretching out fondly on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Neglecting the credible arguments of authors like Peter Levanda, who argue that Satanism is the actual, implicit religion of all Nazism, we can more easily assert that the Nazis shared the Satanic abhorrence of Judeo-ideas. Their anti-Semitism was a synthesis, as is belied is that well worn trope of Nazi propaganda about ‘the Jew’ being the ‘carrier’ of the ‘disease of communism’, behind which they recognised the Semitic morality propounded by Moses and Christ alike.

And Satanists too, as we will see, are rarely immune to a fondness for the far right, partly because they also tend to view the left wing as a camouflage for Judeo-Christian values, what Nietzsche called slave morality. But for a Satanist, racial anti-Semitism is by no means inevitable. The famous founder of the Church of Satan, for example, Anton LaVey, was born Jewish. The trouble remains: if you reject Judeo-Christian morality and all its offspring (from Socialism to Humanism), what real grounds are they to criticise Hitler’s geopolitical programme?

I first stumbled upon Boyd Rice randomly on YouTube. There in the margin of the screen a short was entitled, ‘Boyd Rice talks to Nazi boy Tom Metzger.’ The interview was taken from what looked like an American Nazi chat show, called Race and Reason, which even sported, in the great chat show tradition, a sidekick Nazi to co-host besides Metzger, the latter a leading light of the American far right and Race and Reason‘s main man. This Metzger reminded me of the one of the Nazis in The Blues Brothers; there’s something intrinsically un-American about being a Nazi, even on the far right of the political spectrum there, and this was evidently a soul that had come of age under the duress of utter alienation. He sported an appalling toupée and his ruddy face was disfigured by a permanent sickly smirk, the sort sported by a cuckold that had taught themself to enjoy the humiliation. Much more interesting was the lithe, smug, handsome and bright looking young man sat opposite him—the guest, Boyd Rice, introduced by Metzger as a composer of industrial music.

As a rule the radical right possesses a limited power of morbid allure, but there was something genuinely compelling about this guest, who looked more like a hipster than a Nazi. While there was something haughty about Rice (at one point he dismissed politics as being for people that “couldn’t control their own lives”), he was an agreeable enough guest, and he and Metzger happily discussed the brilliance of Mein Kampf, the essential ‘Aryan-ness’ of industrial music, and the ‘racialist’ music scene in general.

As a rule the radical right possesses a limited power of morbid allure, but there was something genuinely compelling about this guest, who looked more like a hipster than a Nazi. While there was something haughty about Rice (at one point he dismissed politics as being for people that “couldn’t control their own lives”), he was an agreeable enough guest, and he and Metzger happily discussed the brilliance of Mein Kampf, the essential ‘Aryan-ness’ of industrial music, and the ‘racialist’ music scene in general.

The whole thing didn’t make much sense to me, but it started to when Rice began to regurgitate what I promptly recognised was basic Satanic stuff, predominantly lifted almost verbatim from Might is Right. Hence, I figured, his affiliation with, or indifference to, these Nazis: they were all, morally and metaphysically, bad guys. When they watched He-Man, they rooted for Skeletor. If the Holocaust had happened (Metzger presumably thinks not), it would have been a Good Thing. The weak have it coming. And so on.

Between that happenstance discovery and my viewing Iconoclast, Larry Wessel’s intoxicatingly good four-hour documentary/portrait of Rice, I added a few more items to my Boyd Rice YouTube collection, including a couple of poems/songs of his (extolling war and hate respectively), and some debates he’d conducted on old talk radio shows with an Evangelical preacher called Bob Larson. These latter were genuinely engrossing, with Rice (whom a Wikipedia search confirmed as a high ranking member of the Church of Satan) presenting the Satanic, social-Darwinian perspective on issues like domestic violence, but doing so with such camp relish it was difficult to establish the extent to which he was larking about, especially as Larson was constantly erupting in extremely entertaining indignation.

Other YouTube viewers were similarly unsure where Rice’s head was at. ‘HAIL SATAN’ proclaimed one. ‘Oh my gawd, Boyd’s hilarious, he just cracks me up,’ opined another. Wikipedia informed me that this division ran deeper still, with a genuine and hotly contested controversy surrounding Rice’s flirtation with Nazism. Jewish friends in the avant-garde passionately attested his innocence, while others couldn’t even forgive the Fascist aesthetics that abounded in his music and performances, let alone his conspicuous fraternisation with members of the far right. None of his critics on the left, however, gave a shit about the fact that he was a bona fide, card-carrying, high-ranking Satanist. So long as you don’t identify the weak on racial grounds before annihilating them, Satanism was apparently politically correct (and there were some who attested that, even in his Satanism, Boyd was basically having another of his japes).

My interest thus piqued, the arrival of Larry Wessel’s Iconoclast pleased me immensely. The documentary is broken up across three DVDs, and over its four hours takes a broadly chronological approach to Rice’s biography, stitching together its story with the help of a large cast of talking heads, including lashings of Rice himself and many of his collaborators and friends from down the decades. Beginning at the beginning, Iconoclast kicks off in Rice’s native Lemon Grove, California, examining the cultural influences that helped mould his character as a young man.

While my preliminary investigations into Rice had already prepared me—to a degree—for a dose of the unexpected, I was still bewildered to find myself subject to a introductory discourse, courtesy of a middle-aged, camp, broad-shouldered Rice (looking and sounding like a cross between Morrissey and Aleister Crowley), on Tiki.

For those of us born tragically far from the golden age of Tiki, and don’t even know quite what it is, think cocktails with little wooden umbrellas, bras made of sea-shells, and every other stripe of Hawaiian kitsch you could envisage gracing a revamped nightclub in seventies Lancashire. Sat in an actual Tiki bar—a drab looking establishment that we later learn Rice himself had designed—Rice attempts to provide some contextual edge to Tiki by discoursing on the duck-and-cover Cold War anxiety this faux-exotic fad arose in, though the presiding sense is that, for little or no reason whatsoever, something in Boyd Rice’s extraordinarily singular soul resounded to Tiki, just it would later resound to Nazism, Satanism, Abba, the Partridge Family, Tiny Tim, the Manson murders, and a host of other obsessions, kitsch and/or brutal.

An unusually tenacious monad, when Rice’s soul gets its teeth into something, it doesn’t let go—his enthusiasm for all of these lifelong hobbies appear undimmed in his middle age. When an old consort of Anton LaVey’s is later interviewed (Rice was close friends with LaVey), she describes Rice as having the soul of “an ancient warrior poet”. While I’m not wholly unsympathetic to this hagiographic definition (I definitely acquired, over the course of Iconoclast, much admiration for Rice’s audacity and imagination), it strikes me that this soul is also, at the very, very least, seventy per cent geek. Rice is a born collector, anorak, annalist, enthusiast, and it is his succession of intriguing, amusing, unpredictable obsessions that Iconoclast focuses on.

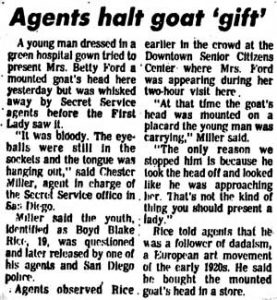

Many of these obsessions were creative, active ones, ranging from industrial music, painting, writing, photography, and – famously—pranks: Iconoclast’s segment on Rice’s Lemon Grove trailer park adolescence is heartily enriched by his precocious flair for practical jokes. I was still getting my head around the Tiki mania when I found myself bellowing with laughter at the accounts given by Rice’s teenage friends and accomplices of Rice’s comic terrorising of his Californian hometown, particularly his invention of an unpronounceable and nigh-inedible special at the Taco Bell he worked at, where customers could also be exposed to Rice suddenly plucking a passing moth from the air and popping it into his mouth without missing a beat. Rice’s larking about (amplified and ennobled by his early discovery of Dada) arguably found its apotheosis when he presented then-first lady Betty Ford with a skinned sheep’s head.

All of which is desperately funny, mostly thanks to another significant aspect of Rice’s character: he is a born raconteur. Droll, camp, mordant, and with a fine line in impersonations, Rice’s own recollections are one of the unforgettable treats of Iconoclast. In his later years Rice seized the opportunity to meet and ingratiate himself with an incarcerated Charles Manson, becoming a regular visitor and even confidant of the famous felon. Rice’s wan anecdotes from this period, enlivened by his note-perfect Manson drawl, are a genuine delight. “Before we begin,” says Manson (vis-à-vis Rice), the first time they meet, “we need to get one thing straight…” There may be two of them sat there, Manson explains, “but there’s only one consciousness, one soul” at the table. “And I thought,” exclaims Rice, his voice modulating from his Manson impression to a fruity eruption of fan-boy enthusiasm, “this is just fucking fabulous. I’ve been sat with Charles Manson for five minutes, and he’s already giving me the I-am-you-you-are-me shtick…”

It’s quintessential Boyd Rice: On the one hand, an attraction to, and (apparently) affinity with a genuinely dark character, on the other an ability to collect the experience and simultaneously turn it into something kitsch, camp, ‘fun’ (a favourite word of Rice’s). In his anecdotal analysis he goes on to observe that Manson’s capacity to inveigle you into his own imaginings was obvious even within the penitentiary walls, noting approvingly Manson’s talent for “fantasy”. This power, certainly, had much to do with the Tate-LaBianca murders—Manson so adjusted the parameters of his followers’ reality that at least some of them could insouciantly transgress the greatest taboo this ‘consensus’ reality presents—murder. Now a Satanist may or may not murder, but I understand that it is their contention that the potential to manipulate values reflects the fact that there are no intrinsic ones—that everything is permitted, which is really just an extrapolation (some would say an excessive one) from the observation that, morally at least, everything is possible. It is possible to befriend killers, to laugh at them or with them, to have fun with them.

Iconoclast falls over itself to extract the poison from the sting of Boyd Rice, and it left me with the distinct impression that the motivation for this was as much his as it was Larry Wessel’s. Yes, it transpired that, come 2011, few people sympathized with a quasi-white supremacist inclination that, post-punk, looked like it might have a future in the wider counterculture. Nowadays, Rice apparently can’t do a gig without anti-Nazi protestors picketing it. We see one such protest in Iconoclast, and while the protesters prove predictably naïf sorts, it isn’t these alone that find Rice’s happy affinity with the far right offensive. Most others, less easy to satirise, will simply curl their lip to learn that the person performing in their town or city (or sat opposite them at a dinner party) dug Nazis and Nazi memorabilia. I sensed that Rice, for all his don’t-give-a-fuck bravado, has started to aggressively mellow with age, and begun to feel secretly bashful about the sincere young fascistic nihilist he was in his early twenties, everything about which has become fast obsolete.

Fortunately, there is enough contradictory material in Rice’s life and character to enable him (and a sympathetic filmmaker) to adjust the past as they’d like. Rice’s aforementioned enthusiasm for Dada, for example, is very powerfully accentuated in the opening third of Iconoclast, implicitly encouraging the viewer to bury any proceeding glimpses we have of Rice’s later politics beneath mountains of postmodern salt. As such I find Iconoclast, and Rice himself, directly mendacious: Where, pray, is that fascinating, easily accessible—and unequivocally damning—cameo on Race and Reason?

Which is not to say that the contradictions and paradoxes Iconoclast draws upon are not important facets of Rice’s character. The film’s protracted coda, which focuses on its subject’s contemporaneous middle age, presents a man for whom these contradictions have stopped pulling in different directions and started to mix and coalesce, resulting in a sadder, milder, less assured and much more sympathetic individual. Indicative is a reunion between Rice and his old Evangelist sparring partner Bob Larson. The two men clearly quite like one another, and Larson, whose tone is otherwise woodenly condescending, is quick to note the bona fide maturation of Rice’s moral and metaphysical worldview. While one might be inclined to differ with Larson’s interpretation that the hand of Jehovah is discernible in Rice’s tentative entertainment of reincarnation (rather than the traditional Satanic tenet of posthumous oblivion), it is difficult to argue with him when he calls Rice up on the fact that his recent moral motto—that he finds people treat him pretty well so long as he does the same—loudly echoes the kernel of the Sermon on the Mount (do unto others…).

Appearing on Race and Reason (really can’t get enough of that quaint alliteration), a younger Rice brought up the implicit hypocrisy in the public demonization of Charles Manson over the deaths of six people, while the US army incinerated millions in Vietnam. This observation (that killing, the ultimate social taboo, is frequently state-sanctioned) is far, far older than Raskolnikov, who yet made it with much more élan over a century ago. Regardless—what was Rice’s point? That we should focus our moral outrage on the larger atrocities? Course not. Rice has never been a satirist. A satirist illuminates moral inconsistency in an attempt to bolster the moral. Even if his Nazi flirtations did largely lack political purpose or malice (as Adam Parfrey suggests), Rice’s wallowing in the human capacity for cruelty and hate is more infantile than adolescent, the child licensed to fling its feces at the wall. And it is this touch of the polymorphously perverse that helps elucidate Rice’s inability to distinguish between concentration camps and Tiny Tim, Satan and Tiki. It’s all fabulous fun to Rice, hypnotised by a moral smear as much as he is the lurid colours of a Ray Dennis Steckler film (another of Rice’s countless enthusiasms).

And what of it? demand his defenders (wheeled out, one after the other, in Iconoclast)…

Well, I’ll concede that most tabloids luxuriate in the same murky material beneath the lumpy cloak of indignation, and that the darker side of human nature fascinates almost everyone. And I’ll concede that to celebrate brutality unabashedly remains original in the current cultural context, as well as being, by and large, entirely harmless – taboo dominates human consciousness so effectively that there’s plenty of room for a few thousand transgressives to go careering about the temple. But is the result really great, in the sense that Nietzsche, say, was great? In his Race and Reason appearance, Rice insists that, contrary to popular opinion, Mein Kampf is far from ‘turgid’. I beg to differ. It’s terrifying, yes, unique, yes, but it is also extremely badly written. And just in case I am accused of parroting some kind of consensus, let me also assert that that other (less notorious) text treasured by Rice, Might is Right, is also extremely badly written, that its style reeks, and that anyone with the least literary sensibility will laugh in its face. That isn’t an opinion, it’s an aesthetic fact. If Rice wants to wax lyrical about the superior and the inferior, someone should tell him that, in terms of literature and philosophy, he inhabits a slum.

When it comes to a flair for experience, however, a way with an anecdote, a capacity to juggle enigmas, and an ability to be an original person (no mean feat), I confess that Rice is second to none. Regardless of its suspect blind spots and bouts of sycophancy, so is Iconoclast. Not only did Wessel have the judiciousness to realise the value and power of fascination such an unusual documentary would have, but he had the steady hand and nerve to pull it off. Don’t miss this absorbing film.

Thomas McGrath

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress