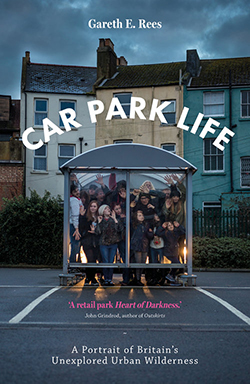

Car Park Life

As I savour the thrill of the landscape mutating in significance before my eyes, I realise that a car park can have as much mystery and magic as a mountain, meadow or lakeside. When we hurry through them with groceries on our mind they may look indistinguishable, but like a second-hand book where the previous owner has scrawled notes in the margins, they are full of intriguing human detail.

Car Park Life (p.15/16)

It is fair to say that Gareth E. Rees is obsessed with retail car parks. Car Park Life is divided into chapters that deal loosely with aspects of these physical spaces — as a location for illicit sexual activity, violence, and a place to park when shopping. He also talks about car parks in terms of spiritual space and this book is the result of his three-year exploration. I’m hesitant to say that Rees has been gathering evidence for his theories in all that time, because there are few if any theories here. The book is about Rees and car parks, following him around as he navel gazes.

A lot of time is invested in the breakup of his marriage. Rees doesn’t see the breakup coming, which happens on page 184, but there are constant references to it throughout the book. (His wife and children don’t share his passion; we have the pitiful image of them waiting in the car, in the rain, after he makes a stop to visit a retail car park that particularly excites him.) Each chapter is effectively a standalone essay, offering slight variations on a theme: The access road, signage, boy racers doing doughnuts, Asda, Brexit, arguments with one’s partner… In this fashion Car Park Life plods along much as it starts. But there is a denouement of sorts in that Rees ends up attending the 4th World Congress of Psychogeography in Huddersfield, which consists of two days of lectures, performance and walks. Here he leads a walk around Sainsbury’s car park. Nothing happens on the walk, and he admits he hasn’t anything to say to those in attendance. Only later does he discover the tour passed close to a dead body, which had lain undiscovered for some time. This for Rees illuminates the point, ‘validates’ his obsession. Car parks are filled with analogies waiting to be discovered.

Just beyond the KFC, we come to a dainty wooden footbridge. Beneath it is our much-anticipated destination: a dried-up stream, just as Dan described, lined with pebbles and running in a straight line through the car park, bordered by steep inclines of dry grass, lined with pine trees.

(p.75)

Fortunately, none of this is without humour. Rees is an honest writer and acknowledges the absurdity of his quest. I admire the fact that he is suddenly self-conscious about the t-shirt he wears for the psychogeography world congress, with its smug slogan: ‘My Psychogeography is better than your psychogeography.’ He is glad that the cold weather means it remains covered for the duration. He also makes some nice observations, such as the inconsistencies between cemeteries and car parks — one is a beautiful place no one visits unless they have to, the other a place that people visit all the time, although it remains flat, ugly and soulless. He points out the absurdity of the anthropomorphised request ‘Please recycle me’ — whose voice is this? In another reference to his hard-put-upon wife, visiting a Premier Inn becomes a haunted reminder of better times. The uniformity of the hotel chain, once a comfort to him, only heightens his sense of loss. I wish Rees had been able to keep this up.

I don’t dislike Car Park Life, but I was glad when it was over. Early in the book Rees establishes the car park as a microcosm of the universe, and the fact that he is drawn to them as if there is no choice in the matter. A higher power and all that. The position of car park trolleys, for instance, reflects cosmic influence, etc. The problem in setting the bar at such a giddy height is that everything soon becomes an understatement. Maybe that’s the point.

Clark Johns

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress