Two Ian Curtises

Unlike many stars who died tragically young, Ian Curtis left only fragments behind. Beyond the canon of Joy Division music and a smattering of televised performances, there is little, almost nothing, by way of recorded documentation.

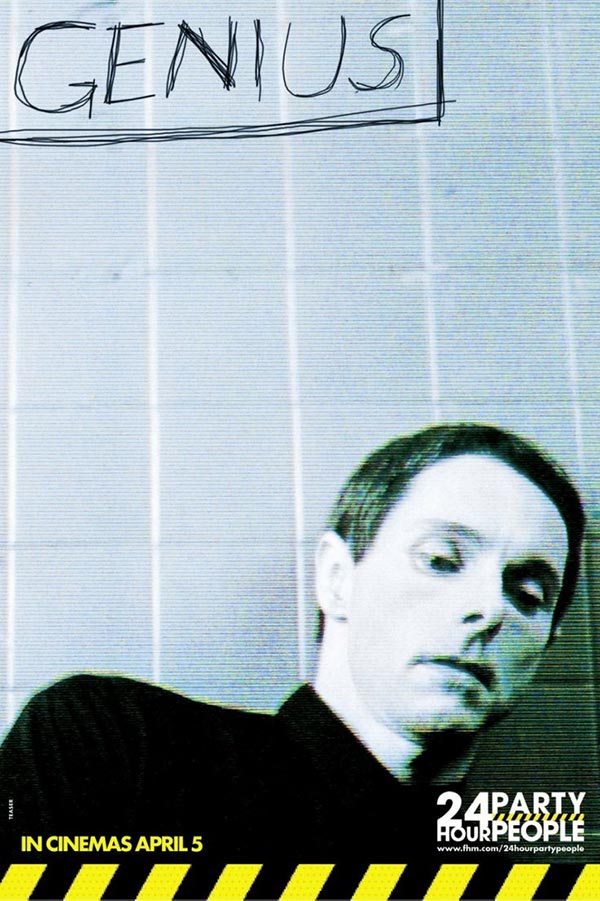

Instead, our image of Ian Curtis comes through those who knew him and via two dramatizations, music biopics a half decade apart. The first of these biopics is 24 Hour Party People (d: Michael Winterbottom, 2002), the story of Factory records, depicted here as a game of two halves as the heavy gravitas of Joy Division lurches suddenly into the pantomime of the Happy Mondays. The second is Control (d: Anton Corbijn, 2007), about Joy Division and Ian Curtis specifically.

Sean Harris plays Curtis in 24 Hour Party People. His manner is a joyless lobster, a pinched threat eager to deflate anyone with expectations equal to or greater than his own. In Control it is Sam Riley, a more kindly and sympathetic presence, but ill equipped to cope with domesticity or stardom.

These opposing performances construct two very specific portraits of Curtis. Only those who knew the artist, of course, can say which, if either, is the more accurate. Likely the truth is an amalgam of the two. But that’s barely the point. An archive interview with BBC radio reveals Curtis to be warm, quietly spoken, evidently intelligent, and with a sense of humour. It is not the Curtis who yells “cunt!” at Tony Wilson from across a bar room in 24 Hour Party People. Television personality and founder of Factory Records, Wilson recalls that first meeting with Curtis in his book, 24 Hour Party People, itself a story based on the original screenplay written by Frank Cottrell Boyce. The book is prefaced by a suitably elegiac Wilsonism, that some of what you will read is fact, much of it is fabricated. He is a ‘scrawny young lad,’ writes Wilson, ‘at the other side of the pool table. Intense. Intense eyes. And a mouth on him.’ This is Wilson’s introduction to Curtis. It is our introduction to Sean Harris, an actor no stranger to intensity, later finding lead roles as murderer Ian Brady (See No Evil: The Moors Murderers, 2006), a homicidal racist (Outlaw, 2007) and a megalomaniac bent on world domination (Mission: Impossible Rogue Nation, 2015).

The pool table episode appears in Control. But the outbursts differ. Here it begins with Sam Riley sharing conspiratorial looks with his bandmates, before he marches off to a table where Wilson is sitting and confronts him. A whisper in his ear. He calls Wilson a twat for not yet putting his band on the television show he hosts. He gives Wilson a piece of paper that carries the name of the band — Joy Division — and the words ‘you cunt’. Compared with Harris, Riley’s remonstration in Control appears schooled and wise, befitting an actor who would one day play Jack Kerouac (On the Road, 2012).

Both films offer a compelling take on the people and events orbiting Curtis before his death in 1980. Wilson’s biography, unhinged as it is, falls somewhere between the two. For instance, in the film 24 Hour Party People, Curtis has a seizure on stage and is retired to the dressing room, followed by the rest of the band who are pissed by the abrupt curtailment of an otherwise good gig. In Control, the seizure is hardly unexpected and the band continues the song without Curtis. Spirits are high after a ‘blinding’ gig and the band pays no heed to the collapsed singer in the dressing room. Instead they go off to celebrate. In his book, Wilson recounts how Curtis’ epileptic fits were familiar to the band, often taking hold during a live performance. Moreover, the band performed expecting them. ‘Towards the end of a set,’ says Wilson, ‘as Transmission would rev up and Ian hit the third verse at top intensity straight out of the second chorus, Bernard [Sumner] and Peter [Hook] would angle in and watch their lead singer carefully.’ The intensity of Curtis’ spastic dance was an indication of whether he was headed for a fit. They could tell if ‘he was meaning it too much’. Some nights Curtis made it through to the end of the gig; other nights he got no further than that particular song.

Riley in Control blames himself for everything. His infidelity to Debbie, his wife, through to a riot at a gig and all points in between. He pours his heart and soul into his lyrics, but carries so much weight across the latter half of the picture that breaking point is inevitable. Harris, on the other hand, barely seems to care one way or the other. If he takes a moment to write lyrics we certainly don’t see it. His manner is the polar opposite to Riley, far from the sensitive creative type and closer to that of a goon. Ian Curtis #1 probably wouldn’t get along with Ian Curtis #2. When Harris snaps it is unforeseen and unexpected: he watches some boring programme on late night television and hangs himself in front of it. He does not watch as much of the boring programme as Riley, who is gripped through the night by alcohol, inner demons and then another terrible fit as he comprehends the collapse of his marriage, and — as he sees it — a life in flames.

Wilson considered Curtis’ death a ‘romantic altruistic suicide’. Not much by way of recorded documents exist of the real Ian Curtis, but he has his fair share of rumours, just like his peers, dead like him at such a young age. Before the Internet, before these two films, some believed Ian Curtis of Joy Division was discovered hanged not at home but from a lamp post. There was another, stranger rumour that Curtis’ suicide was a fiction, that he simply decided to take flight one day, recoiling from the budding pressure of stardom for a new life as someone else. Jim Morrison, perhaps. Or Sam Riley. Or Sean Harris.

-

Joy Devotion£9.99 – £22.00

Joy Devotion£9.99 – £22.00

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress