The Popcorn King in the age of virus

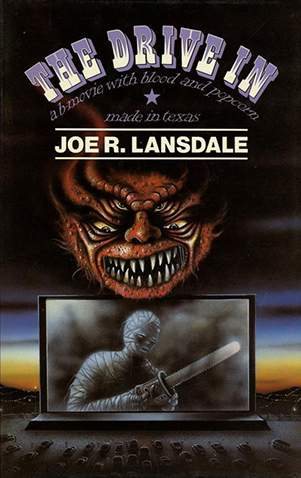

One good thing about being stuck indoors while the world burns is that you find yourself with time to do the little things, the ‘one day soon’ things, like reading the books at the bottom of the pile. Among the books in my pile, high enough to kill me in my sleep should it collapse at night, is a copy of The Drive-In by Joe R. Lansdale. It’s a paperback edition published in the UK in 1989 by the New English Library and has a flattened spine. The cover art depicts a red mischievous face with many eyes and sharp teeth bursting through a cinema screen. It’s been a resident of the book pile for over thirty years.

Physical drive-ins, outdoor theatres where families or couples watch movies from the comfort of their own vehicles, are an American institution. The UK has no tradition of drive-in theatres. Yet this novel struck a chord with me when first published, as it does now, if for a different reason. Set in Texas, the story concerns a group of friends who make the regular pilgrimage to their local drive-in for a late-night horror show, but on this occasion something strange happens and no one can leave. Everyone remains trapped for what might be weeks, perhaps months or even years. Beyond the drive-in is blackness, tentacles, and death. The junk food never runs out and the five movies that comprise the bill continue to roll on a loop. The concession stand becomes a hallowed place, replete with Popcorn King, and the micro-society that constitutes the drive-in collapses and is ultimately renewed.

Joe R. Lansdale is a prolific writer whose work encompasses many genres. The Drive-In is one of his earliest novels and, as the synopsis above suggests, it’s a highly unconventional one drawing on horror, sci-fi and Lord of the Flies. The book appeared at a time when the term ‘splatterpunk’ had a certain cache, but I don’t think I ever considered The Drive-In to be among that type of novel. What drew me to Lansdale’s novel was the all-night horror show at its heart, notably the titles of the five movies playing the drive-in, authentic horror movie titles. Of these five, three happened to be considered ‘video nasties’ in the UK.

Only a few years prior, the home entertainment medium of video had exploded and movies that had been denied a theatrical release in Britain, or unlikely to get one, suddenly found an unregulated outlet via videocassette. The media response was to stir up a moral panic, with ‘violent’ movies being aligned with societal collapse if left unchecked. The clampdown was swift and came in the form of the Video Recordings Act 1984. For a time, many of these movies were effectively ‘banned’. Police raids, fines and even prison sentences ensued in the judicial pursuit of unclassified videocassettes.

Among the movies cited as ‘video nasties’ in the UK were The Evil Dead, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre and The Toolbox Murders, three of the five on the bill at Lansdale’s fictional Texas drive-in.[1] The ‘video nasties’ furore cannot be underestimated. The backlash lasted many years and arguably has never fully gone away. The term ‘video nasties’ is now part of the lexicon of moral outrage. So, it always struck me as a little odd that there wasn’t more evidence of a literary or artistic aspect following in its wake. Outside of fanzines and a cottage industry of fans and collectors that emerged in response to the clampdown, there is little that considers the impact of the ‘video nasties’ as a creative force unto itself. But it seemed to me, back in 1989, that Lansdale’s novel might be evidence of this, the first of a new breed. I thought it in simpatico with the idea of a novel not about the ‘video nasties’ but because of it.[2] I had no way of knowing whether Lansdale, an American author, had this in mind when he wrote his book. He does reference Fangoria, a magazine that was required reading for any discernible horror movie buff and one that would occasionally report on the UK scene. It was only recently that I thought to ask the question, having rediscovered The Drive-in in my uncertainly stacked pile of books. Was Lansdale aware that three of the movies playing his drive-in had featured prominently on the UK ‘nasties’ list. Lansdale courteously responded. In an email dated 5 June 2020, he said, “I didn’t know that. But they struck me as controversial for some at the time.”

The heyday of the drive-in theatre was the 1950s. It should come as no real surprise that the drive-in, like the regular cinema, has been in steady decline in recent years with an estimated 320 drive-ins currently left in the US. The figure at its peak was more than 4,000 nationwide. Regular cinemas, like businesses in general, are suffering because of COVID-19 and fears for wellbeing. They are still closed as of writing. However, the drive-in seems to be entirely suited to the lockdown and in a way the drive-in has always been about social distancing. The vehicle in which you arrive is your self-isolating unit. DriveInMovie.com, an online resource, claim to have seen an increase in traffic to their site recently, a jump of ‘50% as people are looking to drive-ins as a potential entertainment option with everything else being shut down’.[3] Last month Tribeca Enterprises in partnership with IMAX and AT&T announced the ‘Tribeca Drive-In’, a series of shows scheduled for summer across select drive-in theatres. The press release states that ‘The limited engagement series will provide families with a safe, comfortable entertainment experience in cities and towns across the country, as the nation takes steps to emerge from Coronavirus lockdowns.’[4]

Ironic isn’t it, that the drive-in saves the day.

A note about the ’Saw

Unlike The Evil Dead and The Toolbox Murders, The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was not officially a top priority video nasty. There was something of a tier system with the nasties, broadly defined by those films (72 in total) that had been prosecuted or were liable for prosecution as obscene, and those films that while not obscene were still liable to be seized and destroyed. The Texas Chain Saw was one of the latter — not as nasty as some and yet frequently cited in the media when referencing the videocassette menace. The ’Saw has a history of controversy, dating back to the 1970s when it was considered part of a new wave of ‘sadistic’ films threatening British cinemas.

Notes

[1] The other two movies playing the drive-in are Night of the Living Dead and I Dismember Mama.

[2] Only one other work springs to mind that uses the ‘video nasties’ this way. Many years after the fact, David Hinds’ independent horror film, The House on Cuckoo Lane (2014), considers ‘video nasties’ as a malign supernatural force.

[3] https://www.driveinmovie.com/articles/Affects-of-Coronavirus-on-Drive-ins

[4] https://www.tribecafilm.com/press-center/press-releases/tribeca-enterprises-imax-and-att-announce-nationwide-summer-drive-in-series

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress