Panic In The Streets: The Beginnings Of The Pandemic And Outbreak Film

Panic in the Streets (1950) has the distinction of being the first film made specifically about a viral epidemic — I suppose in that one section of the film does show an infected ship heading out into international waters, that this technically also makes it the first film made about a pandemic. While Plague in Florence was more of a morality play and The Last Man on Earth a war of the sexes comedy, Panic in the Streets is the first of what I call the pandemic and outbreak film where we see a contagion spread throughout a population and/or around the world.

Panic in the Streets is set in New Orleans, and stars Richard Widmark as a public health officer who investigates a man found dead on the docks after fleeing from a card game run by the criminal underworld. In quick course, Widmark discovers that the man was suffering from pneumonic plague (one of the three forms that the Black Death takes). He then mobilizes the police to conduct a search for the man’s identity and to find and vaccinate everybody who may have come in contact with the body.

The film comes from Elia Kazan, one of the great directors of this era. Immediately after this, Kazan went on to make films like A Streetcar Named Desire(1951), which brought Marlon Brando to prominence, On the Waterfront (1954), East of Eden (1955), Baby Doll (1956), and Splendor in the Grass (1961), among others. These are films that saw Kazan being nominated for four Academy Awards, winning twice during his lifetime. (Panic in the Streets also won that year’s Academy Award for Best Screenplay Story.)

Panic in the Streets was made at the height of film noir — an era of moody, morally ambiguous stories, usually detective thrillers, shot in B&W. We usually think of film noir in terms of its cliché images — of gumshoes in fedoras and trench coats amid visual stylistics that make high contrast of light and darkness such as the shadows of twirling fans on a ceiling, slatted venetian blinds on the wall and the like. Panic in the Streets is not quite a full work of film noir but shows the genre’s clear influence, particularly in the opening scene where the infected man flees from a card game through the dockyards, a scene filled with some great B&W photography of shadows illuminated along the sides of buildings.

Where Elia Kazan impresses the most is simply in that he went outside the studio and shot in the real world as opposed to the controlled conditions of studio sets like most other films of this era. There are scenes taking place in employment lines, backstreet rooming houses or rundown cafes that strike you with their verisimilitude (and look great in B&W). It looks like a strikingly grounded film. The film arrives at a tense chase climax with the police pursuing criminal kingpin Jack Palance (in his first film role — billed as Walter Jack Palance — where he looks menacingly tall and at his bad boy best).

Whereas subsequent pandemic films created images of figures in contamination suits arriving to place areas in quarantine, Panic in the Streets is more akin to a police procedural of the era — one with Richard Widmark moving through the city in search of the dead man’s identity. The climax of the film, pursuing Jack Palance through the docklands and under the wharfs belongs far more to the regular crime film of the day — one where Palance would probably be a standard wanted murderer fleeing from police pursuit — than anything that holds allegiance to what would later solidify into the tropes of the pandemic and outbreak thriller.

Watching the film in the midst of a real world pandemic (Covid19), you are also struck by the lack of basic precautionary procedures that people use in dealing with a deadly infection. Certainly, we do see a scene where all the police officers who were in the vicinity of the body are lined up and given an immunization shot. However, nobody wears any kind of masking or breathing protection, which would be needed for an airborne infection like the pneumonic plague. We also see Richard Widmark and others handling infected bodies with their bare hands without any rubber gloves or protective gear in sight.

At one point, Widmark returns home and does the correct thing, where he removes his clothing to put it in the laundry because it could be contaminated, and tells wife Barbara Bel Geddes to keep her distance — and then ignores this, simply balling his clothing up and tossing it on top of a wardrobe and allowing her to bring him a cup of coffee and sit in a chair only a couple of feet away from him.

-

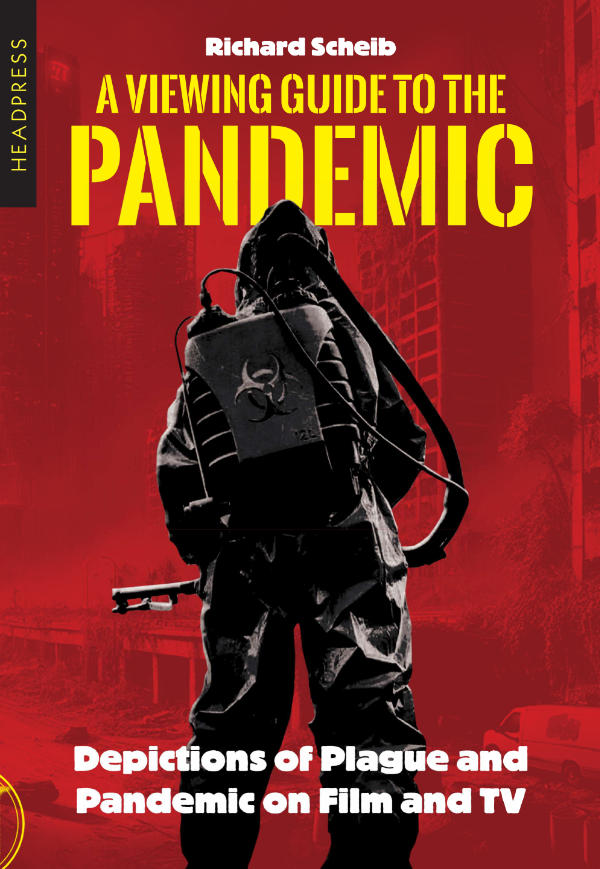

Sale 8% OffA Viewing Guide to the PandemicA film-lover’s lockdown exploration of the history of contagion as depicted in cinema and TV drama. By...£10.95 - £25.00

Sale 8% OffA Viewing Guide to the PandemicA film-lover’s lockdown exploration of the history of contagion as depicted in cinema and TV drama. By...£10.95 - £25.00

- News and Book Excerpts

- A Streetcar Named Desire, A Viewing Guide to the Pandemic, Baby Doll, Black Death, Covid19, East of Eden, Elia Kazan, Evelyn Keyes, Jack Palance, On the Waterfront, Panic in the Streets, plague, Plague in Florence, Richard Scheib, Richard Widmark, Splendor in the Grass, The Killer That Stalked New York, The Last Man on Earth, Zero Mostel

Richard Scheib

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress