How Do You Solve a Problem Like the Marquis?

“I was created by Nature with the keenest appetites and the strongest of passions and was put on this earth with the sole purpose of placating both by surrendering to them.”

—Marquis de Sade

IT’S BACK!

MORE BLOOD. MORE KINK. MORE HORROR.

ABANDON takes audiences on a terrifying journey through the life and writings of the Marquis de Sade during his years spent imprisoned in an asylum. Delivered in rapid-fire, wordless vignettes ABANDON is a theatrical experience like no other, where psychological terror, grotesque beauty, and edgy kink collide to create a horror production that will haunt you long after the final curtain. This is an experience that will haunt audiences long after the final curtain falls.

RATED R - FOR AGES 17+

WARNING: SHOW INCLUDES VIOLENCE, GRISLY IMAGES, SOME NUDITY AND STRONG SEXUAL THEMES

VIP PACKAGE INCLUDES:

• VIP PREMIER SEATING

• COMPLIMENTARY DRINK

• DISCOUNTED MERCH

—The Vegas Company / www.theatre.vegas/abandon

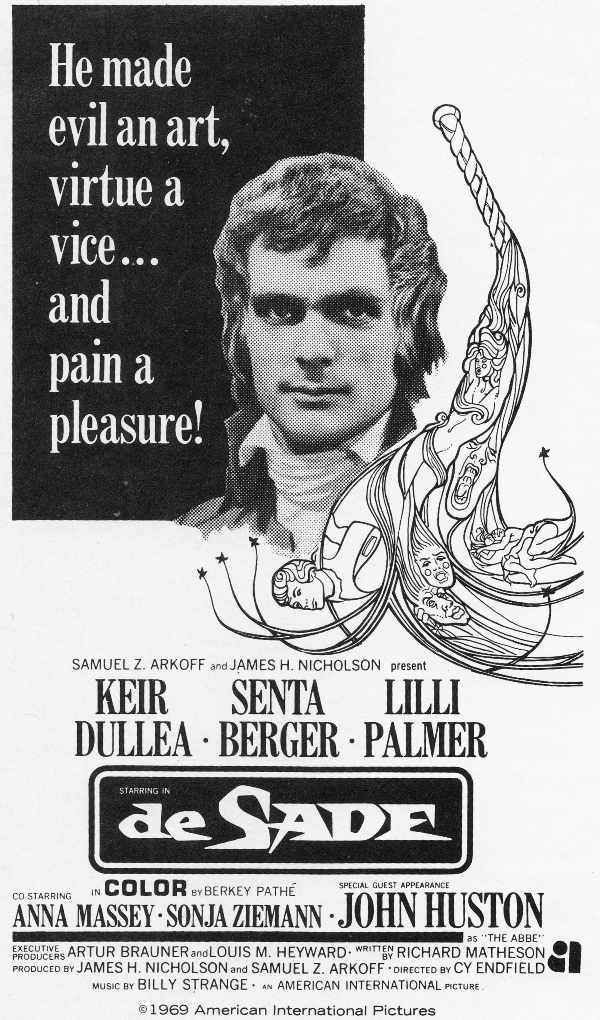

IN A WORLD OF Jeffery Epstein, Harvey Weinstein, Larry Nassar, Jimmy Savile, and countless other sexual predators, the name Marquis de Sade doesn’t cause the same levels of disgust and outrage as it once did. Dead now for over 200 years, the infamous libertine, pornographer, rebel, criminal, pervert, doyen, and victimizer seems more like a historical boogeyman than a man whose life and body of work generated many arguments about the artist, his art, his crimes, and redeeming social value. Championed by the likes of Luis Buñuel, Jess Franco, John Waters, and Ian Brady, and demonized by French philosopher Michel Onfray and iconic feminist writer Andrea Dworkin, Sade’s influence on literary culture has waned over time, but his effect on popular culture is still felt to a certain degree. From Vegas Strip Grand Guignol to LA drag shows, the Marquis’s once verboten surname is now a sure-fire way to bring some tantalizing deviation to any commodity. One of the most infamous movies in cinema history, Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 film Salò, transposed Sade’s The 120 Days of Sodom onto Italy’s fascist past. Pasolini’s unflinching evisceration of the effects of unrestrained power still has viewers debating where critique ends and exploitation begins, but what of its source novel? Is The 120 Days of Sodom (and, by proxy, Sade himself) an unredeemable catalogue of filth and degradation or a dissertation on unconditional freedom using sexuality as its medium of resistance and transgression?

Tears of Blood

The events leading up to the composing of The 120 Days of Sodom could be a novel in and of themselves. (Although not a novel, Joel Warner’s fascinating 2023 study of the history of The 120 Days of Sodom, The Curse of the Marquis de Sade: A Notorious Scoundrel, a Mythical Manuscript, and the Biggest Scandal in Literary History, is just as electrifying). Donatien Alphonse François de Sade, protected by his aristocratic privilege, had been committing sex crimes for at least nine years and received little to no punishment for his debauchery. In 1772, Sade finally crossed the threshold where even his social class could not excuse him from his ravenous, blasphemous appetites and deeds. Sentenced to death for numerous sexual acts that included sodomy with four prostitutes and his male accomplice, Sade fled to Italy with his sister-in-law, with whom he was having an affair. Sade would be caught and imprisoned, but would escape four months later. Hiding out in his estate the Château de Lacoste (wouldn’t that be the first place authorities would look?), Sade could not just lay low and conducted various orgies, which garnered so much attention that he had to flee again to Italy. He would later return to Provence in 1776, and his homecoming was celebrated by hiring several townswomen as servants and using them for his unyielding sexual theatrics. It’s been debated whether the women were kept hostage or if they stayed of their own free will; regardless, the father of one of the women came to reclaim his daughter and pointed a gun at Sade that miraculously misfired.

Sade’s luck would eventually run out, and facing a fed-up judicial system and an incensed mother-in-law, he would be arrested under the subterfuge that his dying mother wanted to see him. (Interestingly, Sade had erased his mother from his life for two decades, and so it is ironic that this single display of compassion from the man whose name became synonymous with cruelty cost him his freedom.) Though the death sentence was rescinded, he was imprisoned first in Château de Vincennes and later in the dreaded Bastille in 1784. The 120 Days of Sodom was written over thirty-seven days in 1785 on contraband paper rolls smuggled in by his long-suffering wife. Hiding the manuscript in a copper cylinder inside his cell wall, Sade had to disguise his composing from the prison officials and could only make slow progress on the narrative. As the French Revolution began on the streets of Paris, Sade, always good at taking advantage of an opportunistic situation, yelled out of his cell window to the mobs of enraged rioters, claiming that the prisoners were being murdered. Eventually the Bastille would be stormed on July 14, 1789, but Sade had already been taken to the Charenton lunatic asylum, unable to find a way to bring his secret manuscript with him. After the looting of the Bastille, Sade believed The 120 Days of Sodom had been destroyed and supposedly “wept tears of blood.”[1]

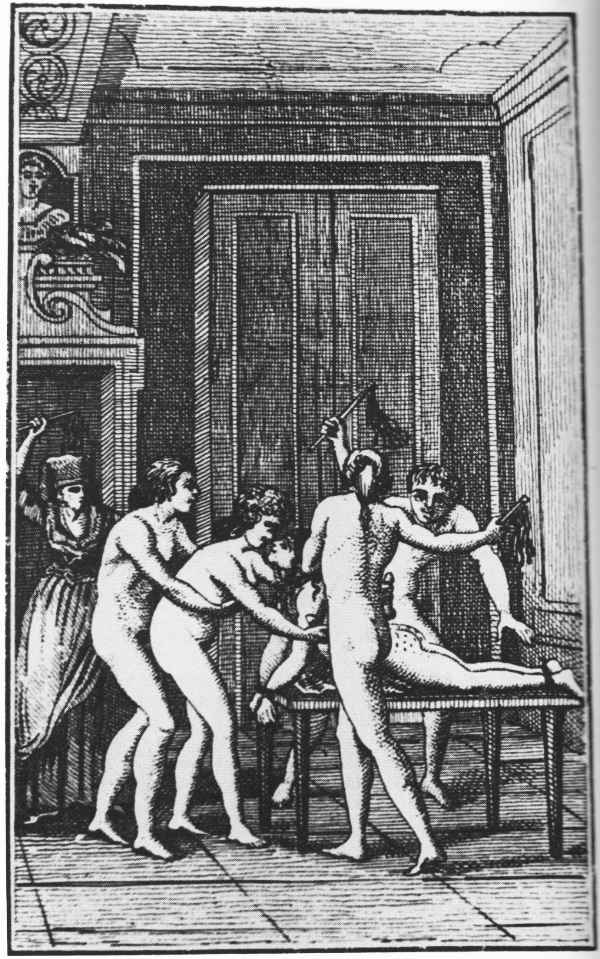

Although Sade’s life would take many twists and turns after the loss of The 120 Days of Sodom, as fate pushed and prodded him until his death, the fortune of Sade’s unfinished novel also had an equally strange odyssey. One of the faceless masses of revolutionaries, citizen Arnoux de Saint-Maximin, found Sade’s papers in the Bastille, and, for whatever reason, decided to keep the manuscript. The vagaries of history do not record what became of this accidental literary preservationist, but the incomplete manuscript was sold to the Marquis de Villeneuve-Transwould (only ‘Part: The First’ had been completed while extensive notes outlined the rest of the novel). The novel was first published by the Berlin psychiatrist and sexologist Iwan Bloch in 1904. Since then, Sade’s descendants and Sade collectors have waged battles over the ownership of the hand-written document. Clearly, this unfinished tale of four libertines who kidnap eight virginal girls and eight virginal boys in addition to their own daughters in order to indulge every perversion imaginable, aided and abetted by four prostitutes, four “hags,” and eight “studs,” struck some disgusting chord in the collective psyche of the twentieth century.

Amoral Satire

Like all of Sade’s work, The 120 Days of Sodom is an amoral satire, halfway between a masturbatory, scatological farce and a deeply cynical social critique, bordering on the pathological. Sade takes aim at Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s belief in the innate goodness and equality of human beings, as well as the concept that nature is benevolent, compassionate, and peaceful. For Rousseau, the natural state of human beings is freedom and to protect our freedoms from being impinged upon by other human beings, we enter into a social contract in which equality and liberty are both sacrificed to and protected by political institutions that rule by the “consent of the governed”. Rousseau’s social contract ensured that in a democracy might does not make right: our intellect and natural sense of equality and morality must guide us to address and cure the social ills that have been produced by the development of civilization. This idealized form of human behavior and the notion that morality would be an effective counter measure to abuses of power in the social contract is thoroughly violated in every way possible in The 120 Days of Sodom.

These violators are the Duc de Blangis (representing the aristocracy), The Bishop (the Catholic church), The Président de Curval (political and legal systems), and Durcet the Banker (economics). These men are Sade’s factotums, representatives of the institutions that Rousseau saw as the pillars of the social contract, charged with the selfless responsibility to safeguard our freedoms as citizens. Of course, these men use their official façades and positions of power to indulge in the rape, torture, murder, exploitation, and degradation of the very people that look to them for protection, compassion, mercy, and assistance. In Sade’s world all power corrupts, not just absolute power. Once someone is given power, this role creates a hierarchy that causes unequal relationships, which then allows one to look down upon those who don’t have the same power, status, and privilege. The validity of power encourages objectification and using people as things by those deemed powerful by the social contract. Those in power will demand submission and will force those under them to sacrifice their freedoms to maintain social order. But whose order? This order is created by the elite to benefit themselves and so they are above the need to share power roles and relationships with others on a more equitable basis. Yet the seductiveness of authority and the license of supremacy inculcates nation and citizen, the strong and weak, the ruler and subject, in the legislature and in the bedroom — as brilliantly portrayed in Liliana Cavani’s sadomasochistic masterpiece The Night Porter (1974).

Out of a litany of atrocities, the ones that involve feces and human waste seem to draw the most attention from critics of The 120 Days of Sodom. Sade’s obsession with defecation and bodily functions and incorporating them into sex, torture, and debasement seems to be the height (or depth) of prurient abjection, and yet there is a metaphoric aspect to this fetishization of excrement. At the same time that Sade was imprisoned scribbling away at his novel, German writer, poet, and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe was ushering in the Romantic movement as a counter discourse to the Age of Enlightenment. Goethe elevated emotion over reason, spirituality and transformation over the arrogance and dogmatism of institutional science, and human sexuality as a joyous experience rather than just a biological necessity. For Goethe, Nature was where we could transcend ourselves and connect with the sublime; its grandiose beauty was a mirror to our inner selves: sometimes peaceful, sometimes tumultuous like the titular hero of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). Nature has a corporeal existence, but, more importantly, it is filled with a spiritual energy: wondrous, mystical, mysterious, empowering, and godlike. The actual physical reality of nature can be transcended to experience and become one with divine essence.

The philosophical “Sturm und Drang” of Young Werther is counterbalanced with a literal shit show in The 120 Days of Sodom. Rather than positing a metaphysical aspect of human existence interconnected with nature, Sade brings us right back to the fleshly carnality of the body: genitals, assholes, offal, shit, urine, vomit, blood, bodily fluids, sweat, snot, spit, and the smells of the body. For Sade, this is what humans and nature are: palpable things that are filthy and debased, meat that decays, rots, and stinks, bags of bones that are deformed, ugly, and wretched, and that can be broken, mutilated, ravaged, and annihilated. The character of the Président de Curval is perhaps the nadir (zenith?) of this concept as there is so much caked-on dirt, shit, piss, blood, semen, snot, and sundry other bodily fluids on his lower body that the encrusted putrefaction has become a part of his penis and anus. In The 120 Days of Sodom, there is nothing behind the physical: no Over-Soul, no living garment of God, no transcendent paradise. The only things that drive nature, and, by extension, human beings, are the need to survive, the seeking of pleasure, and the satiating of appetites at all costs. Although not as coprophiliac-ly obsessed, the preeminent treatise of the Enlightenment, Immanuel Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781) also calls into question the notion that philosophers (or any human being) can objectively understand and pontificate with certainty on abstract concepts which lie beyond the material, spatial, and temporal limits of human experience like God, spirituality, and metaphysics. The hubristic tendency of human reason to fool itself into believing that there is something beyond physical sensory experience and that, even if such forces did exist, we could fully and accurately comprehend them, makes Kant and Sade strange bedfellows indeed.

The Savior is the Ravager

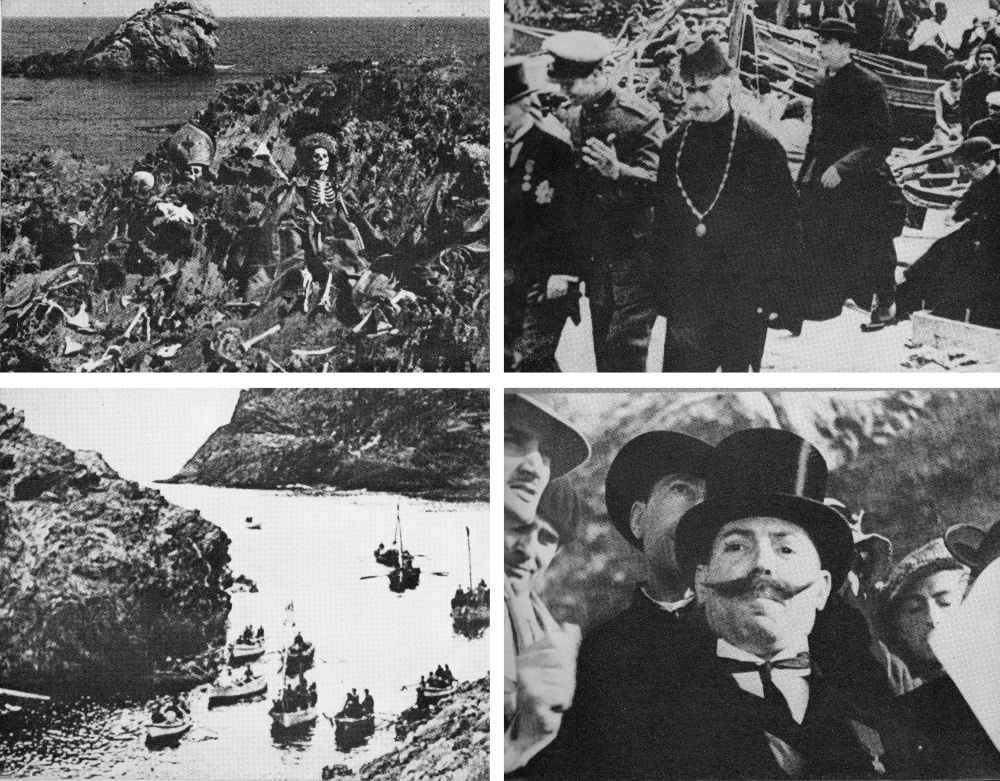

The influence of The 120 Days of Sodom on the arts and popular culture are usually focused on its two cinematic depictions. The concluding section of Luis Buñuel’s 1930 surrealist treatise L’Age d’Or manages to boil down the blasphemous essence of The 120 Days of Sodom into a final slap in Catholicism’s face as the Duc de Blangis disguises himself as Jesus Christ in order to trick an escaping victim to embrace him, and he brings her back to the Castle to be murdered. The savior is the ravager. The Marquis would next appear in Buñuel’s The Milky Way (1969), an absurdist interrogation of just how bizarre Catholicism and its heresies are, and how faith can be even more surreal than anything Breton ever dreamed of. In a short sequence, Sade paces in a dungeon where he rants at a young woman chained to the floor about how ridiculous it is to believe in God. The captive woman is the much put-upon heroine of Sade’s 1791 work Justine, or The Misfortune of Virtue (in the film she is called Thérèse as she was in the earlier 1787 version of the novel). As Thérèse defiantly states her belief in God’s existence, Sade menacingly approaches her and the scene ends. Sade’s atheistic argument actually comes off as extremely logical in comparison with the various nonsensical dogmatic debates engaged in by the different Christian sects throughout the film. By dramatizing the author violently defiling his own creation, Buñuel satirizes what the Church and its instruments have done to the God it has created: debasing, exploiting, and using it for their own selfish desires. Sade’s influence on Buñuel can also be witnessed in his films Él (1953), The Criminal Life of Archibaldo de la Cruz (1955), Viridiana (1961), Diary of a Chambermaid (1964), Belle du Jour (1967) and Tristana (1970); Buñuel once remarked that he was a sadist, but only in his mind, and, clearly, he used his cinema to explore these Sadean concepts and fantasies.

Collective voyeurism

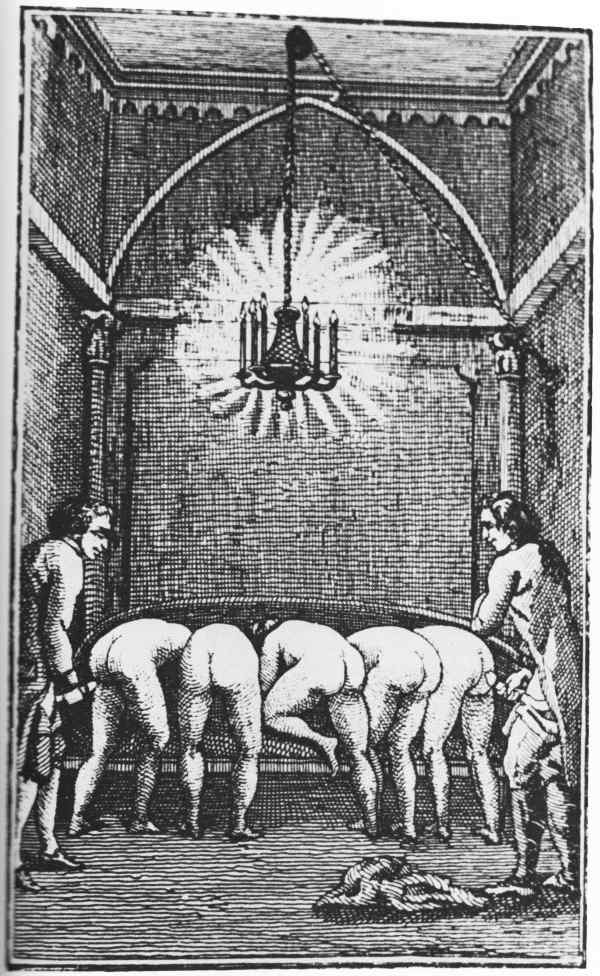

The most famous adaptation of The 120 Days of Sodom is Pasolini’s Salò, which, by its uncompromising use of the novel’s framework, became one of the most controversial films in the history of cinema. Besides the change in era, the biggest difference between the novel and the film is the attitudes towards the libertines and their victims. Sade is on the side of the libertines and relishes the power, pain, suffering, and humiliation they are able to impose on their victims. Pasolini is on the side of the victims, even though they are being dehumanized and fetishized in every way possible. In both, sexuality is a weapon: for Sade it is only for use by the libertines as a destructive force; for Pasolini, it is a two-edged sword, as the libertines wield their power and sexuality to oppress and degrade, but these are not the only forms through which sexuality can be expressed. A critical scene in Salò is where one of the villa’s guards, Ezio, is discovered having sex with one of the maids. The most important law of the libertines imposed over all the inhabitants of the villa (including the libertines themselves) is that all sexual activity must be visible, directed, controlled, and made a public spectacle for all those in the villa to see. No one is allowed to have their own private, personal space or relationship through which to express their own individual sexuality because the libertines’ power in the villa is predicated on surveillance, transforming everyone into objects to be watched (the society of the spectacle becomes the society of surveillance).

This collective voyeurism is part of the systematic objectification and manipulation that is key to the libertines’ domination and pleasure. These planned and orchestrated sexual assaults are shows, plays, theater for the libertines where they get to be both performer and audience member in these cruel vignettes. When Ezio and the maid are discovered having sex in secret, their punishment is death, but before he is shot, Ezio raises a defiant fist in front of the libertines, the victims, and the staff of the villa; his sexuality is the only weapon he has left to actualize not only his resistance but his own sense of self. By having sex away from the gaze of the powerful voyeurs, Ezio is asserting his own sexuality, his own body, his own identity, and his own power. For Pasolini, it is the refusal of obedience, conformity, and supervision that denies the death wish, negates the possession of bodies, and prevents sexuality becoming an exploited spectacle. This concept of empowerment is found in many of Pasolini’s poems and political writings as well as in his Trilogy of Life series of films (The Decameron [1971], The Canterbury Tales [1972], The Arabian Nights [1974]). Pasolini’s homosexuality was an intrinsic aspect of his artistic, social, and political self.

Incredibly, there is a movie that perfectly parodies the excesses of Sade’s novel: Marco Ferreri’s La Grande Bouffe (1973).[2] In the film, four middle-aged men, bored with life and fearful of growing even older, sequester themselves in a villa in order to eat themselves to death, gorging on the most succulent, decadent delicacies possible. While feeding one appetite, they also decide to bring prostitutes to the villa to fulfill their other main appetite. By mistake, a prudish schoolteacher is invited as well and is soon revealed to be the most indulgent libertine of them all. Ferreri’s film takes many of The 120 Days of Sodom’s tropes like sex, death, biological functions, excrement, scandal, and obsession, but transmutes them into comedic gold. La Grande Bouffe displays an aspect of Sade that Pasolini does not utilize in his adaptation: The 120 Days of Sodom as farce through the use of ridiculously over-the-top, excessively disgusting situations as an avenue for wickedly sharp, satiric insights into a hypocritical society.

The abject and the permissible

Perhaps the most sustained artistic exploration of the themes of The 120 Days of Sodom is found in the works of William Bennett and his power electronics/noise project Whitehouse. Bennett’s goal to produce “the most extreme music ever recorded” with “a sound that could bludgeon an audience into submission,”[3] resulted in a whole new genre of music that uses high-pitched frequencies, penetrating feedback, white noise, sub-bass tones, digital roars, trickling discordance, raw rhythms, and silence to force the listener to experience the excesses of experience and transformation (as well as indulging Bennett’s taste for the confrontational). Although the cacophony created by Whitehouse’s instrumentation is pulverizing, it is William Bennett’s vocalizations that drag the listener into the audio space of Sade’s works. Influenced by Yoko Ono’s fearsome screeches, wails, and ululations, Bennett’s screams, barks, yelps, shrieks, rants, cries, and whispers provide a more fitting soundtrack to The 120 Days of Sodom than any other music ever could. (Sorry Ennio Morricone.)[4]

This torturous aural catharsis also extends into the lyrical subject matter and accompanying album graphics for Whitehouse releases: sadism, masochism, paraphilias, exercises of control and dominance, submission, delectation, sexual violence, deconstructing meta-language, and self-critique. In Whitehouse’s music, power relationships are not portrayed as monolithic or unilateral, and they are rarely only expressed through the physical; how power, coercion, and force are experienced are multi-layered and multidirectional, subjects acting on each other through pre-determined roles, assimilated and endured through internal mechanisms, discourses, and social and personal “truths.” Like Sade, there is also humor and satire in Bennett’s work, especially in songs such as ‘Politics,’ ‘Rock and Roll,’ ‘My Cock’s on Fire,’ ‘Lightning Struck My Dick,’ and ‘Ass Destroyer.’ Whitehouse’s works are not about raising questions about what is abject and what is permissible, but, rather, about interrogating people’s responses to these experiential situations: the rationalizations, excuses, needs, wants, and behaviors that they use to give their lives pleasure, meaning, and significance.

A tumult of negative criticism

Following the trial of Ian Brady and Myra Hindley in 1966, the UK enforced a ban on the publication and importation of Sade’s works, which lasted until the late 1980s. While at the University of Glasgow in 1977, Bennett first encountered Sade through translations in a fanzine published by Alan Horne (founder of Postcard Records) and later taught himself French in order to read Sade in its original language, going beyond the surface level gleaning that industrial and noise artists usually display to try to prove their “dangerous” underground cache. Initial copies of Whitehouse’s Total Sex (1980) used pages from the then banned The 120 Days of Sodom as its cover, and Bennett’s collaborative project with Nurse with Wound’s Stephen Stapleton is titled The 150 Murderous Passions, Or Those Belonging To The Fourth Class, Composing The 28 Days Of February Spent In Hearing The Narrations Of Madame Desgranges, Interspersed Amongst Which Are The Scandalous Doings At The Château During That Month. ‘Shitfun’ from Whitehouse’s 1981 album Erector borrows language and imagery straight from Sade’s novel. The track ‘Avisodomy,’ also on Erector, is named after the term for sex acts with birds, which Sade claimed was a specialty at a Parisian bordello, and one of the sound pieces on 1981’s grueling Buchenwald album is named ‘The Days at Florbelle,’ referencing Sade’s final work, Les Journees de Florbelle ou La Nature Devoilee (The Days of Florbelle; or, Nature Unveiled), destroyed by his son Claude-Armand to try to salvage some modicum of the family’s reputation.

Whitehouse’s aesthetics have inspired a tumult of negative criticism, from claims that the band is a sick joke played on gullible listeners to accusations of fascism and misogyny to calls for bans and imprisonment. At face value, Whitehouse appears to be a celebration of all the reactionary, pornographic death obsessions of the twentieth century, but a closer inspection displays a conceptual arc that evolves from the perpetrator’s perspective to the victim’s, much like the difference between Sade’s The 120 Days and Pasolini’s Salò. Starting with 1998’s Mummy and Daddy, Whitehouse’s compositions began to identify with the sufferer, as the focus of violence and pain is either self-inflicted or the result of sanctimonious power relationships rather than the schadenfreude of aggressive libertine predation.[5] Later Whitehouse albums do not wallow in nor ridicule victimhood, but rather conceive suffering and draconian self-critique as transitional states, a shocking satori that could lead to existential breakthroughs: harangues with a mission, tirades to purge the soul, diatribes that force the truth. Whitehouse’s noise shatters both personal and social façades, simulations erected to shield one from authentic living and genuine feeling. This tonal shift is reflected in the title of Whitehouse’s final release, a compilation of their most recent material, The Sound of Being Alive (2016), a lyric from the devastatingly lacerating song ‘A Cunt Like You.’

Whitehouse’s music, much like The 120 Days of Sodom itself, is a litmus test for those who champion free speech and preach total artistic autonomy. When the lines between the avant-garde and purposeful incitement become blurred, the question of the consequences of transgressive expression are often bandied about; fans and critics retreat behind the “serious artistic value” fence. And yet what do you do with works like The 120 Days of Sodom, Salò, L’Age d’Or, Erector, and Great White Death, extraordinary works that violate social and artistic value? These works kick us past the threshold of the acceptable, the moral, the virtuous into a mode of living that acknowledges no boundaries, no gods, no masters. Much has been made of Sade’s motives in writing 120 Days as a self-obsessed masturbatory aid, but the novel has taken on a life beyond Sade’s depraved onanistic needs. Sade didn’t write 120 Days for readers to immerse themselves, like other novels, but, rather, to violently ejaculate readers from the text. The initial reaction of repulsion expressed through shock, refusal, and self-righteous anger lasts until readers start questioning themselves about why are they reading this blasphemy, what attracted them to this holocaust, what excites them and interests them in such desecration? Is it mere prurience or something deeper, liberating, and transformative? Once the reader answers these questions honestly about themselves then Sade welcomes them back to his novel, just as Buñuel does through his films and Bennett does through his music.

De Sade today

Readers, viewers, and listeners who go all the way on these demanding artistic journeys will likely have their perspective changed and maybe their lives impacted by this material in both positive and negative ways. What we do after this occurrence is on us, not the artists or their material. A person has every right to be offended, just as a person has every right not to be offended. It’s the height of arrogance for any person to take away the ability for the rest of us to make up our own minds about what we watch, read, listen to, play, make, or think. Do we have the courage to experience art on our own terms in whatever way we choose without legislation, rationalization, or condemnation? It’s an incredible responsibility, one that is often passed from the individual to demagogues, institutions, organizations, and factions, like the libertines in The 120 Days of Sodom, who use the social contract as a front for their own two-faced exercises of selfish, self-aggrandizing power. As the global techno-fascist imperium’s boot stamps on our faces repeatedly, unendingly, in an orgy of complete victory, maybe we should consider these controversial artists revenge for our complacency with a duplicitous society, our accepting of mediocre art, our embrace of digital dependence, our numbing conformity, and our refusal to see ourselves reflected in the abyss. Regardless of whether one thinks that Sade is a champion of freedom, a psychopathic sexual predator, or hipster fodder for the Las Vegas tourist trap cited at the beginning of this article, 120 Days of Sodom exists and will continue to exist as long as it’s still relevant. Whose fault is that? Does our twenty-first-century global technocratic-capitalist hyper-individualized obsession with self, superciliousness, and satiation at any and all cost make Sade the perfect philosopher for our times? The crimes may be his, but the choices are ours, whether we like it or not.

-

Sale 9% OffGhost of an IdeaA critical analysis of the 21st-century fascination with the past, from horror films to haunted music....£9.99 - £23.00

Sale 9% OffGhost of an IdeaA critical analysis of the 21st-century fascination with the past, from horror films to haunted music....£9.99 - £23.00

Notes

[1] Joel Warner, The Curse of the Marquis de Sade: A Notorious Scoundrel, a Mythical Manuscript, and the Biggest Scandal in Literary History (Crown, 2023).

[2] If you ever wondered what Salò might have looked like if it had been filmed as a life-affirming polymorphous orgiastic “black comedic fairytale,” check out Miklós Jancsó’s frisky Private Vices, Public Pleasures (1976), a titillating depiction of the scandalous Mayerling incident, being the alleged murder-suicide in 1889 of Rudolf, Crown Prince of Austria, and his mistress, baroness Mary Vetsera. The exercise of state power has never been depicted as so joyously erotic, but it would not last in the face of reactionary forces.

[3] “Susan Lawly: FAQ v. 3.01”

[4] Friendless Churches, the musical outlet of Rafe Grimes’s postmodern pagan aesthetic terrorist mystery cult Wyrd Isle Collective, has released a dark ambient/industrial “alternative” soundtrack to Salò, a menacing layering of classical music, screeching waves of static, and guttural utterances, sounding like James Leland Kirby’s musical incarnation the Caretaker getting sonically molested by Gulaggh.

[5] These themes are evident in Bennett’s songwriting and not in the pieces written by Whitehouse’s other members.

- Other

- 120 Days of Sodom, Andrea Dworkin, Belle du Jour, Fight Your Own War, Ghost of an Idea, Goethe, Grand Guignol, Immanuel Kant, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jess Franco, Joel Warner, John Waters, L’Age d’Or, La Grande Bouffe, Liliana Cavani, Luis Buñuel, Marco Ferreri, Marquis De Sade, Michel Onfray, Miklós Jancsó, Moors Murderers, Nurse with Wound, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Private Vices Public Pleasures, Salò, The 120 Days of Sodom, The Arabian Nights, The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron, The Night Porter, Whitehouse, William Bennett, William Burns, Yoko Ono

William Burns

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress