Fascination: David Hinds on Jean Rollin

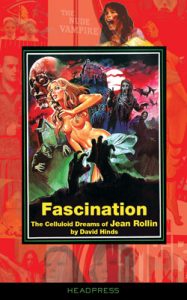

Those of you who saw our Killing For Culture documentary, The Death Illusion: Murder, Cinema and the Myth of Snuff (and if you haven’t—don’t hang around, view it here) will already be familiar with the talents of David Hinds, who directed it. Now, Hinds is set to become an author as well as a filmmaker, as Headpress publishes Fascination: The Celluloid Dreams of Jean Rollin, a study of the outrageous, intriguing film director. We spoke to Hinds to find out more…

Headpress: Hi, David. For those of us that don’t know, who is Jean Rollin?

David Hinds: Jean Rollin is a unique French filmmaker who specialised in erotic horror and the fantastique. Outside of cult film circles his work has gone unnoticed. His films are deeply personal, nostalgic and obsessive. They bear the mark of a genuine auteur. His films are difficult to define as he doesn’t strictly adhere to common genre traits. The world he creates is populated with deserted beaches, crumbling castles, sex, doomed romanticism, blood and seductive female vampires. In fact it is impossible to think of Rollin without picturing semi-clothed female vampires prowling deserted cemeteries and beaches.

The first screening of his feature debut The Rape Of The Vampire is quite notorious. What happened there and why?

Rollin’s theatrical debut caused a similar reaction to that of Luis Bunuel’s scandalous Un Chien Andalou. The audience, no doubt expecting a conventional Hammer-esque costume romp, were infuriated by the film’s deliberately bizarre narrative and outlandish imagery. So much so that they tore the cinema to pieces. They threw things at the screen and tore out the seats. Rollin was in attendance and he was pursued and attacked by several audience members. The screening caused a riot and police had to intervene.

Are there any other similarly distinct anecdotes surrounding Rollin’s life and work?

There are none quite as extreme as the screening of Rape Of The Vampire but there are a few interesting anecdotes.

Rollin lived for his art. He loved to tell stories. When he couldn’t make films he wrote fantasy novels. As his health deteriorated in the nineties he still insisted on making his deeply personal films. When he made The Two Orphan Vampires he literally directed segments of it in bed whilst recovering from dialysis treatment. He was an extremely dedicated artist.

One of Rollin’s most problematic films was the 1974 title Les Démoniaques. Rollin was working on location with a large multi-national crew and there were continual language barriers. There is a scene in the film were a gang of pirates torch a shipwreck. The superstitious local sailors had only sanctioned the burning of one particular boat and supervised the shoot with loaded shotguns. Rollin and his crew shot the scene virtually at gunpoint, ensuring they didn’t enrage the locals. The finished scene was done in one long take and then edited down and it has a genuine sense of energy and danger.

To add to Rollin’s problems, his lead actress on this film turned out to be a nightmare prima-donna. She was a cover girl and the idea of making independent cinema did not interest her at all. She sulked throughout the entire production and made things as difficult as possible. When it came to filming the climatic finale it was a one-take deal as it was too expensive to reshoot. The sequence depicted the lead girls tied to a shipwreck that is being engulfed by the tide. The cover girl sulked and walked off the set claiming she was cold. This was the last straw for Rollin, who chased after her and literally dragged her back to the set by her hair as she screamed and protested. The crew actually tied her to the boat and let the sea carry her out—and they left it until the very last possible minute to save her from drowning.

Moving on to your new book: why did it need to be written, and what has been your approach to the subject matter?

Until recently, Rollin’s large body of distinctive work was rarely reviewed or appraised. Only a small number of cult film publications devoted pages to his films—the excellent Immoral Tales by Cathal Tohill and Pete Tombs featured an in-depth chapter on Rollin but there was no single volume dedicated to his work which really surprised me. Rollin is one of the most distinctive and important filmmakers in European cult cinema and there was a distinct lack of coverage of his films and career. When I started writing the book I knew I wanted to highlight his full artistic career and explore his approach as filmmaker. My intention was to provide an exhaustive look at his roots, his films and his obsessive themes. Some of his films are rarely referenced, never mind explored in-depth. I wanted to shine a light into the dark corners and paint a full picture of this unique artist.

What was the experience of writing the book like? You got to know Rollin in the process of doing so, is that right?

The experience was very challenging but also extremely rewarding. I don’t speak fluent French which made the research much tougher. Also, there wasn’t a tremendous amount of material available on Rollin. Thanks to David Kerekes I was able to obtain Rollin’s home phone number and he agreed to be interviewed. I travelled to Paris to meet him at his home and he was incredibly gracious and kind. Despite my lack of understanding of the French language we managed to have a great discussion about his career and his films. We shared a written correspondence for a few years after this. Jean also put me in touch with one of his producers, Lionel Wallmann, who was living in Florida. Lionel was able to source several of Rollin’s more obscure films for me.

You’re a filmmaker as well as a writer. How do you personally rate Rollin as an artist? He’s usually quite sneered down at?

His work was often referred to in France as ‘Rollinades’—this was a derogatory term that meant cheap and clichéd movies. I personally feel that Rollin is one of the most distinctive auteur’s in European cult cinema. He genuinely expressed himself and explored his obsessions, creating a deeply personal body of work. His films are full of beauty and emotion. Images from his work stay with you. I find his spontaneous approach to filmmaking inspiring. He never used storyboards—something that would be alien to contemporary filmmakers. When it came to directing he allowed the film to develop organically. He felt the film as it was created. He was challenged and inspired by his chosen surroundings and his performers. He let the mood of the location determine how a scene was shot. When you watch a scene from a Rollin movie you are experiencing his undiluted vision. Rollin shot what he felt. He was a true artist.

Finally, what was the main takeaway from writing it?

I suppose the main takeaway from writing the book would be that I hope his films find a wider audience. His work is now finding audiences on the Blu-ray format and it’s time he gets the credit he so richly deserves. On a more personal level, Rollin’s spontaneous, organic approach to filmmaking has made me a more confident independent filmmaker. Dispensing with storyboards makes for a much more challenging, creative and exciting approach to shooting. You find you capture images in the moment that you wouldn’t have got had you drawn them first. A location can be your most powerful character.

Want to know more? Pick up a copy of Fascination: The Celluloid Dreams Of Jean Rollin by David Hinds. Available in paperback and a limited special edition hardback.

Want to know more? Pick up a copy of Fascination: The Celluloid Dreams Of Jean Rollin by David Hinds. Available in paperback and a limited special edition hardback.

A journey into the fantastique world of the blood, erotica and lesbian vampires of “outsider” filmmaker Jean Rollin.

Thomas McGrath

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress