Amanda on TV Movies

HEADPRESS: First things first—how did you come to have such an interest in the TV movie? A nd why is the genre so interesting?

nd why is the genre so interesting?

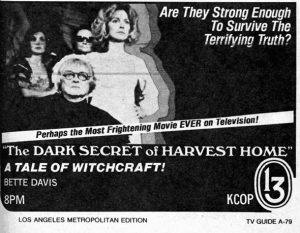

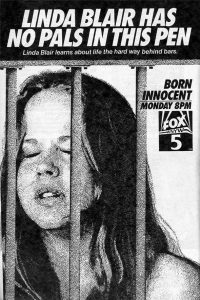

AMANDA REYES: I grew up during the heyday of the television movie (1970s), and it was a gateway for kids like me into the world of horror and exploitation. Certainly, these films had to go light on the harder content, such as sex and violence, but many of the classic telefilms, like Trilogy of Terror and Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark were genuinely chilling. And, it is because those films managed to be so effective that it makes the telefilm so interesting to me. Of course, TV movies aren’t just horror, and have focused on different genres depending on the era, but it was how telefilms introduced me to horror that really struck a chord with me, and I wanted to write about some of these oft-forgotten titles.

The relationship between Hollywood and TV is a curious one. How does the TV movie fit into this history and what does it tell us about it?

TV movies came about for several reasons, but the main crux of its creation arose from the networks looking to produce original content that they could directly profit from. In the 1960s, the Screen Actors Guild was seeking higher residuals for theatricals that ran on television, but the films themselves were on average at least four years old. They also had to be censored, and, along with rights and residuals, it was a bit of a costly affair. TV films are tailored for the medium, were cheap to produce and could be marketed as an “event,” since it usually only ran once or twice in primetime, which fed into their popularity.

However, despite some quality films coming from television, there is still a gap in the recording of the history of the TV movie. I’m not sure why that is, because networks sought to create content that could be consumed by general audiences, but also approached topical subjects, such as feminism, AIDS and nuclear war. I think both the actual history of the telefilm and how worked as a cultural touchstone need more reflection.

In short, it was because of their popularity with general audiences and the desire to either explore current issues or just piggyback on popular genres, such as horror, that these films became cultural touchstones, or water cooler talk, since they were experienced on such a large scale.

With regards to the stars, was the TV movie a springboard to Hollywood, a graveyard for it, or something else entirely?

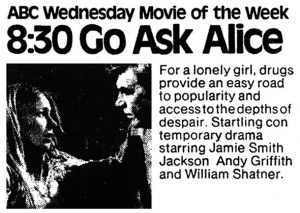

While dozens of actors worked primarily in television for a variety of reasons, there are two intriguing threads that can be seen in actors who worked heavily in TV movies. For one, many actors known for episodic television, usually sitcoms, used the TV movie as a way to show audiences their wider range. Actors like Elizabeth Montgomery, Robert Reed, Andy Griffin and Barbara Eden were masterful in choosing very untypical roles that allowed audiences to view them through a new lens. Montgomery may have been the most successful with telefilms such as The Legend of Lizzie Borden and A Case of Rape. She would go on to be nominated for several Emmys for her TV movie work.

The second thread you may notice in TV movies is that a lot of classic actors from the golden age of film found a lot of work in the genre. While viewers and critics saw this as “slumming it,” by employing actors considered past their prime, the actors themselves often viewed it as a great avenue to continue working. A good example of using classic actors to challenge ageism issues is Do Not Fold, Spindle or Mutilate, which is an early 1970s telefilm starring Myrna Loy, Mildred Natwick, Sylvia Sidney and Helen Hayes, playing a group of alcohol swilling pranksters who get in over their head when they invent a girl for a computer dating service and lure a stalker into their lives. Hayes was nominated for an Emmy. The writing is full of great dialog, and the film truly showcases everyone’s talents, while also working as a way to introduce younger audiences such as myself to these fantastic talents.

There was a tendency towards sensationalist content in the genre, how do you account for that – simple economics or something else?

Yes, there was a lot of sensationalism in the telefilm, but do I think reverting to sensationalistic marketing and/or content occurred more often than what was already happening in the TV movie’s theatrical counterparts? Not really. For every Robert Altman there’s a Ted V. Mikels and that’s what makes the experience of film so much fun. Since television had to tread lightly in the sex and violence departments, they did use really salacious ads, film titles and premises as a way to lure viewers. Some of the best titles are Satan’s School for Girls, Mysterious Island of Beautiful Women and Diary of a Teenage Hitchhiker. Of course, none of these films would ever go too far over the edge, but, again it was a nice gateway into the world of exploitation filmmaking, and many of these telefilms were quite good and remain sought after classics to this day. In short, I do think some of it was economics, as many films had to be churned out quickly, but filmmakers were still looking to entertain, any way possible, and these films were good enough to put viewers on their couches night after night.

What were the economics like, though, in general? Real shoestring stuff, or were TV movies actually quite profitable?

You are correct that TV movies were made on only a fraction of what a theatrical would be produced on. They also had very little time to make a movie, and some were shot in less than two weeks! However, despite working against all odds, the TV movie, particularly in the 1970s, was extremely popular. Between the three networks, there was “Movie of the Week” programming almost every night of the week. What kind of actual profits the networks made is unknown to me, but they were certainly rewarding enough to keep up the intense production schedules.

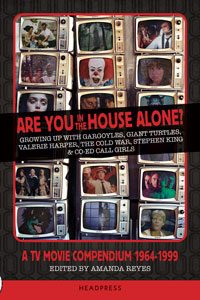

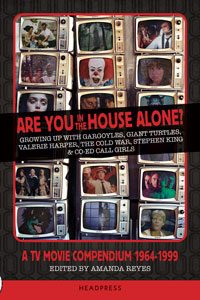

Tell us about the book. Why did you feel it should exist, and what was the process in creating and compiling it?

There’s some very good reading out there, to be sure, but many TV movies remain “lost films,” which are due re-discovery. The idea to put together a book on TV films, split between essays and reviews actually came from Headpress, and I was contacted by the publisher because of my blog, Made For TV Mayhem, because it concentrates on the made for TV movie. Many reviews had been turned in already, but there were holes in there, including no reviews for the big classics such as Duel and Trilogy of Terror. The essays were tailored to bring together subgenres where several titles could be bandied about and analyzed on a larger scale, but again, this section was a bit threadbare when I came on. So, on my end, I merely expanded on what the publisher had already envisioned, suggesting topics that I thought might be interesting (such as the USA Network TV movie era), and I brought in a few more writers. After I received an essay on Stephen King, I realized that there was so much more to say, so we also created a section dedicated to King’s small screen work, which I think is a really great addition. Because so many different types of reviews had already come in, I also created a small section on the mini-series as well as an appendix for non-network telefilms or ones that had come out after 1999. It’s an expansive book in terms of attempting to cover as much as possible, but it would be impossible to review everything, so I relied heavily on what the contributors had access to and wanted to write about. I think it came out really, really well.

What are the main highlights for you in the finished volume and why?

As I mentioned, the Stephen King section is really great, and I was happy we expanded from our initial essay. I also think the essays cover a wide range of topics, and are obviously coming from a variety of voices. For instance, Jennifer Wallis contributed some really intriguing academic essays on how TV movies handled issues such as sexual assault and child abuse, while one of my own essays is a much lighter look at some of the more popular actors and actresses working in the telefilm. The reviews themselves cover many films I’m not sure have been reviewed with any real depth before this book, including the rare slasher-lite She’s Dressed to Kill, from 1979, and the remake of The Bad Seed from the 1980s. This gives readers a wider view of the immense scope of the television film in terms of just how varied and intriguing the product was.

Want to know more? Pick up a copy of Are You in the House Alone? A TV Movie Compendium 1964–1999, edited by Amanda Reyes. Available in paperback and a limited special edition hardback.

Want to know more? Pick up a copy of Are You in the House Alone? A TV Movie Compendium 1964–1999, edited by Amanda Reyes. Available in paperback and a limited special edition hardback.

At the top of its game, the US telefilm was a huge ratings winner. These films made a big impression on many young viewers and are fondly remembered, as well as finding a whole new generating of fans.

Thomas McGrath

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress