They Don’t Make Movies

Before the Internet and digital media, death was a strange and elusive beast. Death captured on film was uncommon and the exploitation of such footage was conducted in an almost hushed and reverential manner. Early images of death and catastrophe retain their power for this reason. The 1937 newsreel footage of the Hindenburg disaster is a case in point. Those familiar with the footage can hardly forget the stark black and white scenes of the luxury airship arriving at an airfield in New Jersey and suddenly exploding in a ball of flame. The images of the fiery ship and of men falling from the sky are etched in the collective memory, as is the choked monologue of the news reporter at the scene, trying to comprehend the catastrophe and his own place as spectator to it. This is material that dates back over 80 years, and while I can’t remember when I last saw the Hindenburg footage, it resonates with me more than my last visit to an online shock site, where death and calamity clips often stream alongside punk’d and porn clips as entertainment. Clicking the Google link to one of these sites only a few moments ago (‘ShockGore Serve You The Most Shocking Video In Internet Including Reality Gore In The Whole World!’) spurs a virus alert on my computer. It’s isn’t an issue of ethics that keeps me away from the sight of bloody carnage in this instance, but the threat that my computer might crash if I continue.

In the first edition of Killing for Culture — mine and David Slater’s book about images of death of film — there is no discussion of the Internet. Back in 1991, when the book was first published, the Internet as we know it didn’t exist. For the update published a few years ago, we effectively wrote the book afresh to redress this balance. Technology had levelled the playing field in the intervening years, the camera phone creating newshounds of us all. But in updating the book it wasn’t enough to simply document the wealth of these images in this new age, we had to address the society that had, to some degree, been defined by these images; a society in which death is reduced to clickbait.

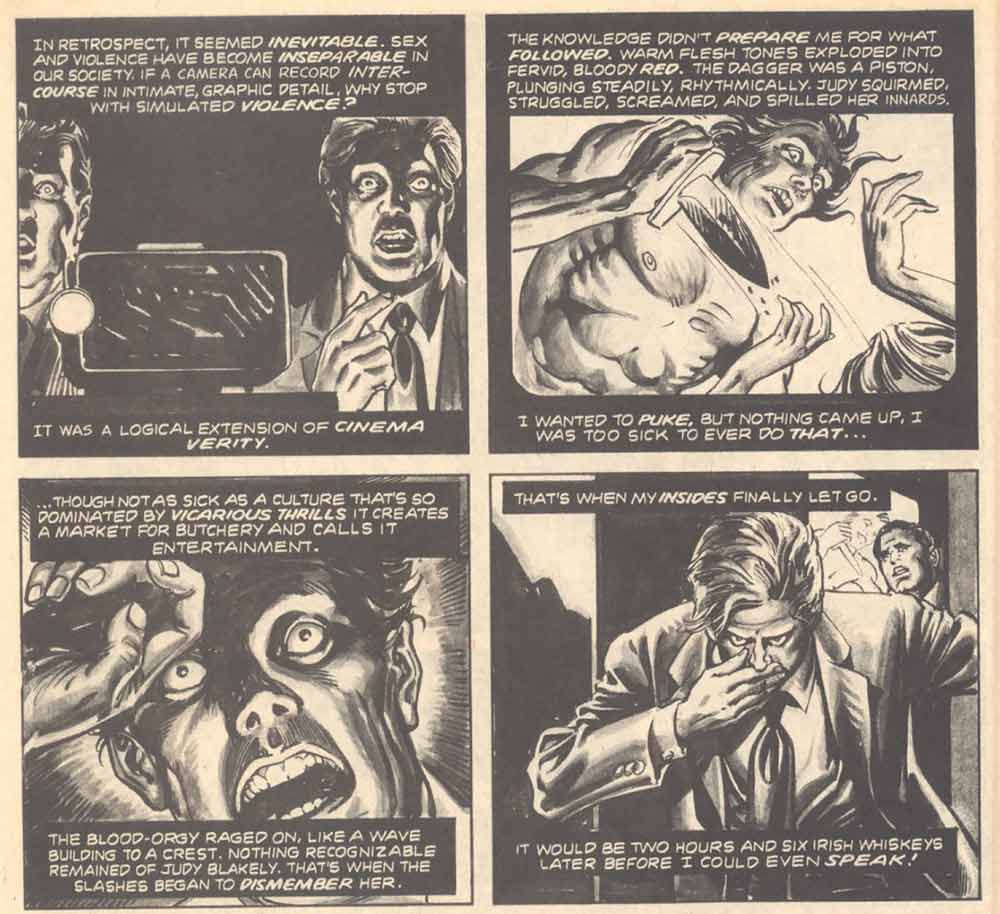

The concept of the so-called ‘snuff’ film took hold in the mid-1970s. The rumour that pornographers were committing murder on film, to satisfy an audience now bored with movies like Deep Throat, was unfounded but inflamed the public imagination. It’s difficult to shake off a moral panic; a notion such as a ‘snuff’ film becomes absorbed into the cultural fabric because it is too profound an idea to ignore. The catalyst was the motion picture Snuff, released in 1976. Exploiting public anxieties with a title and advertising campaign that implied on-screen murder, Snuff was a low-budget hit. A flurry of movies and TV shows followed that played on the idea of death as pornography, which served to codify the ‘snuff’ film rumours.

I was thinking this because of a comic strip that had recently been brought to my attention.

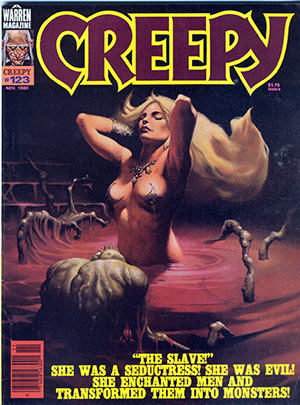

The strip in question, ‘They Don’t Make Movies,’ appears in issue no 123 of the black and white horror anthology, Creepy, published by Warren and cover dated January 1981. Rumours of ‘snuff’ films had been circulating for a few years at this point. What is interesting about ‘They Don’t Make Movies’ is that it is a rare instance of the comic medium tackling the concept of ‘snuff’. I can think of no other comic story from this era that deals explicitly with the theme. The story’s writer, Gerry Boudreau, and illustrators Carmine Infantino and Alfredo Alcala, all had a pedigree in the world of comic books, working for DC, Marvel, Gold Key and other companies as well as Warren.

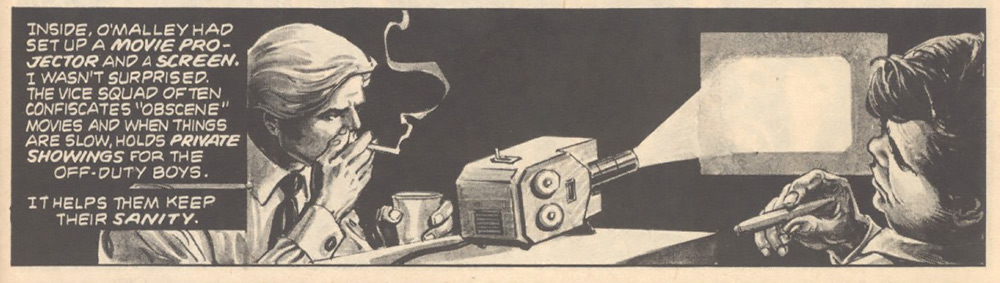

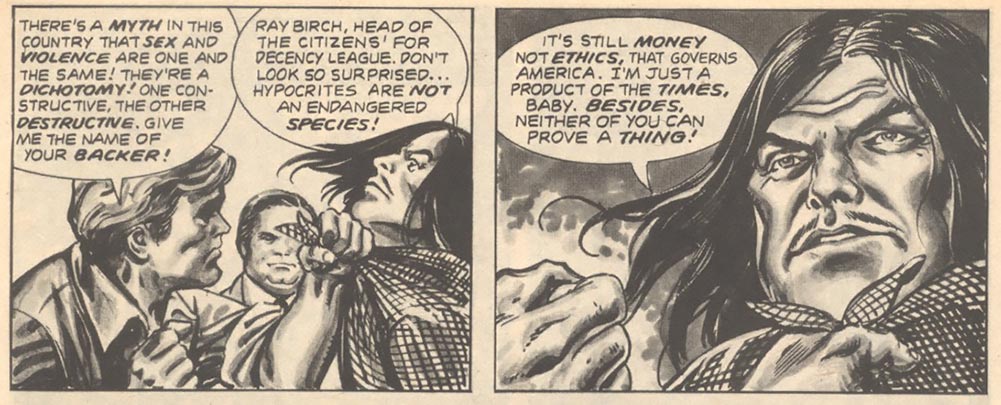

The story concerns journalist Willie Lynds, who, having researched a news article about prostitution in Miami, stumbles on a ‘snuff’ film. An old buddy on the vice squad, Kevin O’Malley, shows him a film recently confiscated by his department. It looks much like any porno loop to begin with but ends with the brutal murder of a hooker who Lynds had recently interviewed. With a little detective work, the men discover that the ‘snuff’ film has nothing to do with the Mob or the adult film industry, but was made by one Jeffrey Wakeman, a young filmmaker with artistic aspirations, who considers his work “the definite statement on American in the 80’s”. Wakeman’s ‘snuff’ film backer turns out to be the head of an anti-pornography organisation. “Don’t look so surprised,” Wakeman tells the two men, “hypocrites are not an endangered species.” The story ends with Lynds and O’Malley dispensing their own rough justice. The final panel shows an upbeat Lynds agreeing to accompany his buddy to a screening of Gone with the Wind, lamenting “They don’t make movies like that anymore”.

The art in ‘They Don’t Make Movies’ is a grey wash style that I always find a pleasing alternative to line art in black and white comics, although it is hardly representative of the work normally associated with either Infantino or Alcala. The story itself doesn’t stray far from the ‘snuff’ rumours that were floating around at the time, nor the true-life source of those rumours: the rumours were quickly traced to an anti-pornography group in Cleveland, Ohio. An article in one of the group’s newsletters of December 1974, penned by the head of the organisation, used the imagined threat of ‘snuff’ as a rallying cry to help boost its membership. (For the full story, read the book.)

As noted, there isn’t an awful lot of representation of the ‘snuff’ myth in comics. In Killing for Culture we were only able to list a handful, and none of these were contemporary works, or works that tackled the issue in as direct a way as this story does, or were published by a mainstream company. There’s no real mystery behind this: the idea of ‘snuff’ films doesn’t afford a writer a lot of wiggle-room in a story restricted to only a few pages. Gerry Boudreau imbues his story with elements lifted from movies and television shows of the day, distilling what in effect had been floating in the ether with regards to ‘snuff’. It’s interesting to speculate on whether Boudreau would have been familiar with cartoonist Jay Lynch. I think it’s likely. Lynch worked in underground comix but was also a journalist and wrote an investigative piece about the ‘snuff’ rumours, as well as attending the world premiere of Snuff and deciding early on that the whole thing was bogus. Lynch’s July 1976 article for Qui is echoed in ‘They Don’t Make Movies’ and we might even consider him to be the inspiration for ‘Willie Lynds’. Unfortunately, Boudreau isn’t around to ask any more.

Thanks to Stephen Sennitt for bringing ‘They Don’t Make Movies’ to my attention.

-

Killing for Culture£9.99 – £39.99

Killing for Culture£9.99 – £39.99 -

The Bloodiest Thing That Ever Happened In Front Of A Camera£15.99 – £25.00

The Bloodiest Thing That Ever Happened In Front Of A Camera£15.99 – £25.00

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress