“Sparky! Oh, Sparky!” The Charm and Chill of Children’s Records

Last month it was announced that Paul McCartney would be re-releasing Rupert and the Frog Song, his animated short film originally released in 1984. The film’s central song, We All Stand Together, is also set for re-release as a picture disc. I remember the film and the song all too vividly from the first time round: an inescapable sense of lumbering boredom seemed to pervade We All Stand Together, a cassette of which was given to me by a well-meaning relative.

In their 1948 Guide to Children’s Records Philip Eisenberg and Hecky Krasno warned readers that the purchase of children’s records was a task fraught with risk:

Uncle John beamed as he gave Bobby his birthday present. Breathlessly, Bobby tore off the wrapper and disclosed two record albums – Robin Hood and Alice in Wonderland. Evidently Uncle John does not know much about children (he’s a bachelor); Bobby is only three and will not be ready for these stories until many years later.

The result? Uncle John was let down, Bobby was disappointed, and several dollars were wasted.

Even Bobby’s mother – savvier than hapless Uncle John – might find buying a record a difficult task: hundreds of children’s records were available, all of them ‘dazzling’ her as she entered the shop.

Eisenberg and Krasno’s book was published during the heyday of children’s records (Krasno – really Krasnow – was a producer of children’s songs including Frosty the Snowman). Peter Muldavin, ‘the Kiddie Rekord King’, offers a comprehensive history of the genre: around the time of the First World War several companies produced cheap records containing nursery rhymes and folk tales. By the late 1930s both Columbia and RCA had introduced dedicated children’s series. In the 1940s a combination of circumstances – the introduction of vinyl that superseded the more fragile shellac, closer attention to packaging and design, and the greater availability of record players – led to what Muldavin calls ‘the golden age’ of children’s records.

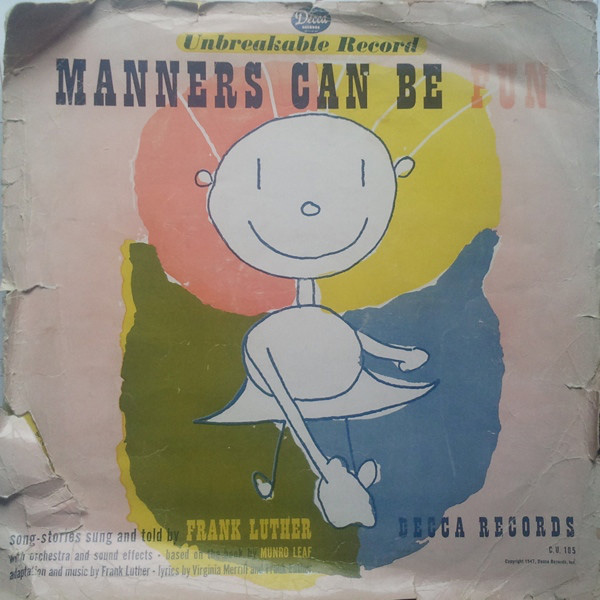

There was no shortage of records that aimed to inculcate good behaviour in children by clobbering them over the head with unsubtle nudges in the right direction. Manners Can Be Fun, released by Decca in 1947, included such rousing tracks as Excuse Me, Toys Belong in Boxes, and Animals Have Feelings. Eisenberg and Krasno dismissed many records like this which often, they advised, ‘leave the child cold’ (they also reminded readers that children tended to be unimpressed by records featuring ‘famous Hollywood or radio stars’).

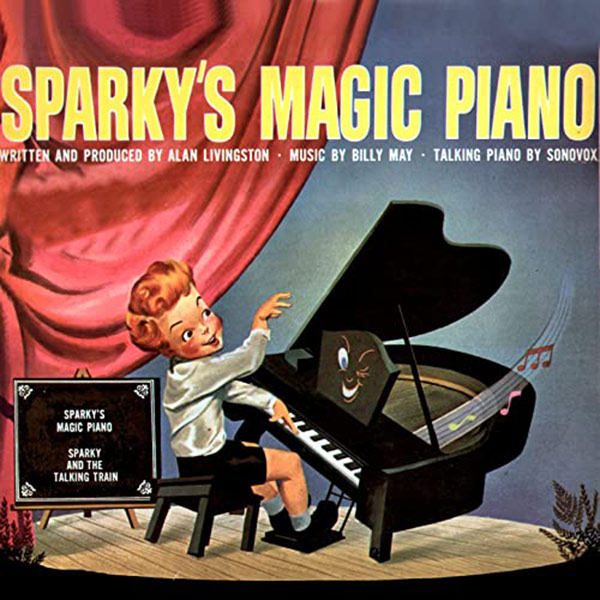

Moral messages needed to be delivered in the context of an engaging story, then. One such example was Sparky’s Magic Piano, also making its debut in 1947. A production of Capitol Records, the story revolves around a young boy, Sparky, who is not a fan of piano practice. One day his piano talks to him, revealing that it can play itself while Sparky merely runs his hands over its keys. A spectacular run of solo concerts follows, and Sparky becomes the toast of the music world. At one concert it becomes clear that the piano has had enough of filling in for the idle Sparky, however, and promptly goes on strike. Sparky’s embarrassment as he sits helpless in front of the expectant audience is relieved by the revelation that, of course, it was all a dream. Although Sparky had other audio adventures – with a talking train, a conductor’s baton, and his own echo – the piano proved to be his most memorable companion. The duo had a brief renaissance in the 1980s, when an animated version of the story was produced featuring the voices of Mel Blanc, Tony Curtis, and Vincent Price.

My childhood encounter with Sparky, though, was in the original audio form. My dad, fondly recalling his own memories of Sparky and his piano, borrowed the record from Bradford Central Library for us to listen to. He would have done well to follow Eisenberg and Krasno’s advice: ‘Parents are sometimes impatient to give their children the stories they loved when they were young … forgetting that they enjoyed them at a much later age than they imagine’. For those who have never heard the original recording, the moment when the piano first speaks is a sound to freeze the blood. The piano’s ‘voice’ was the product of the Sonovox, or talk box, which picked up the sound of a person’s voice when applied to the throat. The result was a rather grating, somewhat demonic, electronic warbling. In the story, the piano also walks on and off stage, suggesting something like the possessed piano in Freddie Francis’ Torture Garden. James Valentine’s podcast, Why were children traumatised by Sparky’s Magic Piano?, suggests that I wasn’t the only child haunted by the infernal ivories.

The intended message of Sparky’s Magic Piano, however, was that children should do their piano practice. Sparky’s dream/nightmare has a salutory effect: the tale ends with Sparky applying himself to his scales with renewed vigour. The story would ‘give children who are struggling with the piano a sense of power and superiority’, thought Eisenberg and Krasno (albeit also adding: ‘We are not so sure that it will make children want to practice, but it will be entertaining.’). It was one of several records – along with Rusty in Orchestraville which used a similar conceit of talking instruments – that was recommended by some as a means of encouraging children’s musical ability.

Although records for children would continue to be successful beyond their ‘40s and ‘50s heyday – check out the 1960s series Tale Spinners for Children for some appearances by Donald Pleasence – the rise of children’s TV would soon become a serious competitor for children’s attention and pocket money. Children’s magazines that encouraged a collector mentality – ubiquitous in the 1980s and ‘90s and despised by parents everywhere – did their bit to keep recordings for children somewhat in vogue. The Once Upon A Time series, for instance, paired a cassette with a slim magazine containing a fairy story and ran for 60 issues (small fry compared to Dinosaurs! magazine, which locked parents in for an impressive 101 issues as children feverishly collected the parts to make their very own plastic T-Rex).

I’m glad to see that Sparky and his piano seem to have stood the test of time, though – nightmare potential aside. London’s Royal College of Music still uses the record as the basis for a listening activity for children. However creative these young musicians are, though, I would hope that their own ‘Magic Piano voices’ – for this is the final task suggested on the activity sheet – bear little resemblance to the original.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress