‘I press the shutter and it’s my way of saying WTF’

I encountered the photographs of Claire Wray while looking at fanzines on eBay recently. Most zines on the sales platform tend to be football related or vintage punk zines; Claire’s featured her own photography, with several devoted to city centre Manchester. The images are without text and are arresting for a variety of reasons. They conjure the same impression I get from Manchester in the ’70s, a book by Chris Makepeace, that collects black and white photographs of the city of that era, a Manchester dominated by its streets and buildings. Everything in it is grim-looking and appears on the verge of collapse, but nonetheless there is a sense of permanence about the place, like an old idea of a dystopian future. In Claire’s zines I saw almost an inversion of this, the characters captured in Claire’s photographs being the landscape, while everything around them is merely passing through.

DAVID KEREKES: What inspired you to take photographs, and why street scenes? Any formal training?

CLAIRE WRAY: I started taking photographs when I was seventeen. I’d left school, gone onto college and found [college] an extension of everything I hated about life so far. I dropped out, worked in a supermarket and around this time I went on a trip to Cornwall. I took control of the camera, in a touristy way, and took some photos that I truly loved. This feeling of taking the world around me, which was overwhelming, and being able to place it within my own frame and have the ability to tell my own story through those photographs was very exciting.

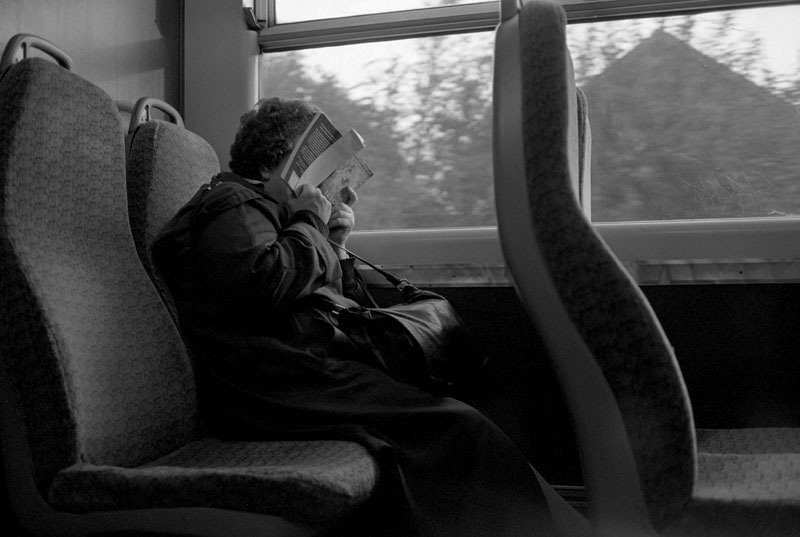

I left the supermarket and studied photography at City College Manchester (CCM) and then Bolton University. It was at CCM that I was introduced to [Henri] Cartier-Bresson by my tutor Margaret. I remember his photographs making my heart flutter. Then I’d check out Martin Parr, Robert Frank, Richard Billingham and Tom Wood — Tom was my favourite. The thought that someone would even whip out their camera on their bus journey home was alien to me. Unfortunately, I haven’t really switched off since.

I went from taking landscapes and seeking conventional beauty before coming to the feeling that a certain beauty exists everywhere and in everything. You just have to seek it out. I guess that’s why street photography has captivated me. I can practice it any time anywhere and it’s a very solitary process and I’m a solitary person.

Creativity has been the at the core of my personality and the foundation of my well-being for as long as I can remember. I would play music or write, but photography has been the main outlet for my creativity since that trip to Cornwall.

The thing that strikes me about your pictures is that they look like they could have been taken at any point in the last fifty years — time stood still but stood still at a very specific point! Would you agree, and if so, why do you think this is?

Crikey! That’s a really interesting question! I mean I’m not trying to be a documentary photographer. The things I love feel timeless to me. Music, films, writing. If there is a timelessness to my photographs, then that’s super interesting and it’s something that I’ll ponder objectively over time. When I head out with my camera in the morning, the only thought in my head is to make a beautiful postcard out of the chaos of the day.

I’m not alone in thinking this, judging from other comments I’ve seen about your photographs, but Manchester (and Blackpool) in these images seems crestfallen. Is this what you see through the viewfinder, or do the pictures ‘simply’ come out this way?

Well, Manchester definitely isn’t crestfallen in my eyes. It’s a city on the ascent and it’s very exciting. So many young people making kindness their frontier and doing great things. I love the place more than ever.

I can’t say the same about Blackpool Promenade, but it has its charms! There’s a weird sadness in seaside resorts, I had the same feeling in Coney Island that I did in Blackpool or Toronto. My first zine Sunday was based on the song ‘Everyday is like Sunday’ by Morrissey. I don’t know how many people relate to this, but I’ve always felt an infinite sadness in things that are designed to make folk happy — like funfairs and stuff. ‘Blackpool Pleasure Beach’ — the laughing clown? So creepy.

I think most artists are more driven to create when they’re confused or overwhelmed. Sometimes I think every time I press the shutter it’s my way of saying ‘WTF’ — but it’s just how I process what’s in front of me. It’s not necessarily a reflection of how I feel about Manchester. It’s just where I am and what I’m navigating at the time.

How do other places compare to Manchester in this respect?

When I leave Manchester, I don’t feel that the types of pictures I take change. I’ve always been intrigued by the isolation that comes with living in densely populated areas. [The book] The Lonely City by Olivia Laing was a big inspiration for me. Edward Hopper, too. I’ve taken similar pictures in Greece, but of course everything looks better in the sun.

Can you tell me about your zines?

I was introduced to zines years ago by Café Royal Books who published my ‘42 Bus’ project but in black and white. I thought it was a great way of sharing projects and photographs, but I didn’t have the conviction to pull it off myself until a good few years later. I was troubled by having so many photographs and so few ways to share them, other than social media and the occasional exhibition. So I went through every photo I’ve ever taken— which nearly killed me— put them into categories and came up with maybe fifty sub-categories. My first zine came out in February 2020. I got it in a few shops and then boom! Lockdown! I made a zine every month during lockdown, selling them online.

How many do you print of each?

Between 50-150 copies. One is on the second edition and some others have barely any left and won’t see a second edition. I have a better feeling now for what works and what doesn’t. It’s been a real learning curve.

Do you see zines as an alternative to the traditional exhibition space?

I don’t know that I see them as an alternative to photo exhibitions. I love making prints, mounting them, framing them. I love looking at other photographers’ prints up close. Nothing beats that. But I feel it’s more important to share than it is to be picky about how you do so. Lockdown limited us. To make work and push it out into the world and have it seen, that’s all that matters. Of course, some people are really into zines, and I’ve had plenty of people looking at my work, not through an interest in street photography necessarily, but more from an interest in zines and self-publishing. That’s been really cool.

One of your zines is called The Wall and focuses on the ugly slab of concrete that separates Piccadilly Gardens (in Manchester) from the bus station and the Metrolink. I’ve long since forgotten what the purpose of this wall is, but your pictures put me in mind of a mini-Berlin Wall, except perhaps more abstract. Is life around the wall different to the rest of Manchester that you have noticed?

I like the wall, but not in the way I like Greek Islands. It’s so ugly that it amuses me, if you know what I mean. It’s a real shame because if you look at pictures of Piccadilly Gardens from the 1970s and paintings by LS Lowry, it was so floral. The Piccadilly Gardens area of Manchester needs a lot of work. There’s a lot of anti-social behaviour… and not just from maladjusted street photographers. I’ve been saying for years that I don’t understand how the council operates. They pour their money into making the rich parts of the city look like Canary Wharf. That’s not why people come to Manchester. They might come because they’re hardcore Joy Division fans or want to go to Salford Lads Club or see Old Trafford for the first time, they don’t come for a panini. I’d like to see Piccadilly Gardens, the gateway to the city, look better and feel safer.

Is there an element of disassociation from your subjects when you take photographs? Are you surprised by your images?

Yeah, probably. Being a street photographer requires a certain amount of disassociation — to not care what anybody else thinks about you. That’s a big leap. I know loads of people who are intrigued by street photography, but can’t commit to being the observer, the outsider. You have to stand your own ground and let the world walk by. I’m polite and I like to think that I’m not intimidating. I’m very cheeky, but that’s the most of it. I’d hate to think I’d upset anybody. But if you’re half in and half out, then it’s not really going to work.

I’m not as surprised by my images as I was when I was younger. I’m older and I pre-visualise. I have a better idea of what is going to work and what isn’t. But I love when I’m surprised. It’s one of the reasons I keep using 35mm film. There’s an element of surprise when you scan negatives in four weeks after taking the pictures. Digital can have a predictable pseudo perfection. The aesthetic of film is magic and ambiguous.

There are many shots of people. Some subjects are aware that they are having their photograph taken but others evidently are not. Do you encounter any resistance?

Not really, but I’m not going around like Bruce Gilden. There’s a lot of grey areas and everyone is different. I genuinely don’t want to upset anybody, and I believe that translates in the energy I put out. Like I said, I like to think I’m not threatening. I’m introverted, dorky looking and I have no authority about me. I did once have a lady hiss at me like a cat which really shit me up. I’d rather have been punched in the face. But ultimately, if I’m happy and smiling and comfortable then other people are, too.

You supply background information in only one of your zines (that I have seen), the reason behind a series of photographs taken from the number 42 bus. Why did this journey depress you?

I think commuting in general can be pretty depressing. I read recently that those who live closer to their workplace are generally happier people. I’ve spent a lot of years commuting and it’s not fun, especially when you’re frazzled and tired. Packed in a small place with loads of other people and listening to their phone speakers and chewing and bullshit. When I decided to make ‘42’ a project, I spent more time on buses. I’d board at East Didsbury, get off at Piccadilly and hop back on the next 42 down Oxford Road. It was draining. I don’t miss commuting at all.

You mentioned Joy Division and Morrissey earlier. Are you listening to music while taking pictures? Do you have a playlist?

No, I don’t listen to music while I take pictures. That’s a really boring answer. I like to be aware of what’s around me… especially if I’m about to be flattened by a Deliveroo guy on a bike.

But if I did, I would listen to an album like Easter by Patti Smith or Carrie & Lowell by Sufjan Stevens. Something to pump me up, then something to bring me back down to earth again.

Claire uses a Konica Hexar AF Camera with either Kodak Gold 200 or Fuji Superia 400.

“I’ve used so many cameras: Olympus XA1, XA2, Yashica T3, T4, Bessa R2A, multiple Voigtlander + Summicron lenses. I do miss my Leica M6, but we’re being priced out of our own game. Nothing beats a manual rangefinder with a great 35mm–50mm lens.”

For zines and postcards go to Claire Wray’s store here

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress