JOHN CALE IN THE ’70s

Part One: Hissing In The Distance

In the mid-70s, and in the space of little over a year, John Cale released three albums on Island Records. Taken as a trilogy, explore themes both musically and lyrically which ferment and then erupt in harrowing fashion on 1979’s Sabotage/Live, an excoriating set of previously unreleased and otherwise unavailable songs[1] recorded over several nights at CBGB. While it is inevitable that he will always be recognised firstly in terms of the Velvet Underground, and perhaps secondly as a producer, Fear (released October 1974), Slow Dazzle (March 1975) and Helen of Troy (November 1975) constitute an exceptional period of Cale’s work with a lot to be gleaned from repeated listens.

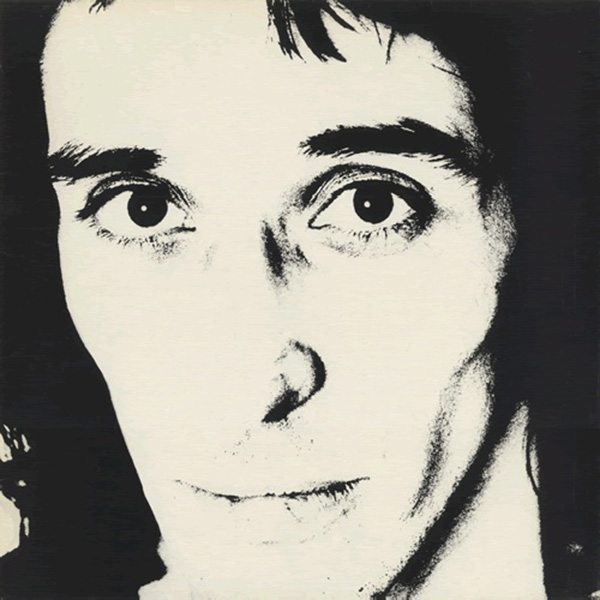

Fear

Fear presents itself in striking chiaroscuro with a gaunt-cheeked Cale in close-up serving as the cover art. Gone is the cream-suited Mitteleuropean figure from the sepia-tinged sleeve of his previous album, Paris 1919; Fear, it seems, is going to be much sharper and starker than its solemnly urbane predecessor. We’re going to be kept on our toes.

We are unsettled immediately by ‘Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend’: three loud, stabbing minor piano chords greet us, the terse second of which violently interrupts the sustaining first. Next, a gently rolling piano line, a very odd-sounding bass, then Cale’s voice, simultaneously distant and much too close for comfort; listening through earphones his inhalation is audible before he starts singing, but the distancing reverb on the vocals lends an ironic gravitas to the hypervigilant figure presented in the lyrics.

The gravitas doesn’t last; the mania grows and by the end the bass is disintegrating as quickly as Cale’s piano and voice with repeated, nearly gleeful shrieks of ‘SAY! FEAR! Is a man’s best friend!’. My lazy assumption was always that the song is a portrait of drug paranoia, Cale not exactly known for being abstinent at the time, and the allusion to ‘I’m Waiting For The Man’ in the opening line might well confirm such a reading. But that said, these days I nearly prefer to see it as a portrait of someone up to their neck in another of Cale’s consuming interests at the time – espionage, military intelligence, sabotage.

And this is by no means the only unhinged track on the record. ‘Gun’, opening side two, revels in viscera and grotesque caricature as it loosely weaves a noir where skilled doctors dismiss anaesthetic as a waste of time and where we must be wary of ‘Big Mama’, keen arsonist and chicken-wire garroter. A big difference here, though, is in Cale’s delivery; conscious of the exaggerated characters as being very darkly humorous, his vocal is consistently deadpan throughout, with the weirdness largely coming from Phil Manzanera’s Eno-treated lead guitar.

Two other narratives take us into seemingly different territory. ‘Buffalo Ballet’ and ‘Ship of Fools’ are both musically gorgeous pieces: warm, elegant, gently melancholic, they nevertheless portray human fragilities, failures and absurdities and suggest these are doomed to repeat. ‘Buffalo Ballet’ outlines at a funereal pace the boom and bust of Abilene, a Texan town, with the focus on community and the double-edged sword of progress; ‘the wealth and the pain.’ ‘Ship of Fools’ is a surrealist lullaby, crisscrossing time and space with some of the most poetic writing on the record. It is interesting to note the references to Carmarthenshire; like Abilene, Ammanford and Garnant (Cale’s birthplace) were boom-and-bust economies, in this instance their fates being determined by coal-mining.

The references to Wales in ‘Ship of Fools’ are a rare intrusion of the personal on an album which exists at a remove from the listener, and even then they exist as part of a non-linear tableau. Fear, for all its warmth of production and often very emotive moments, retains an aloofness at its core; it keeps its distance and in doing so perhaps also helps to offset the anxieties of an artist who had not yet attempted the solo live performances which were inevitably on the horizon. The follow-up, Slow Dazzle, would be both more personal and more visceral, with two particularly notable tracks being linked to his first performance as a bandleader on June 1st, 1974.

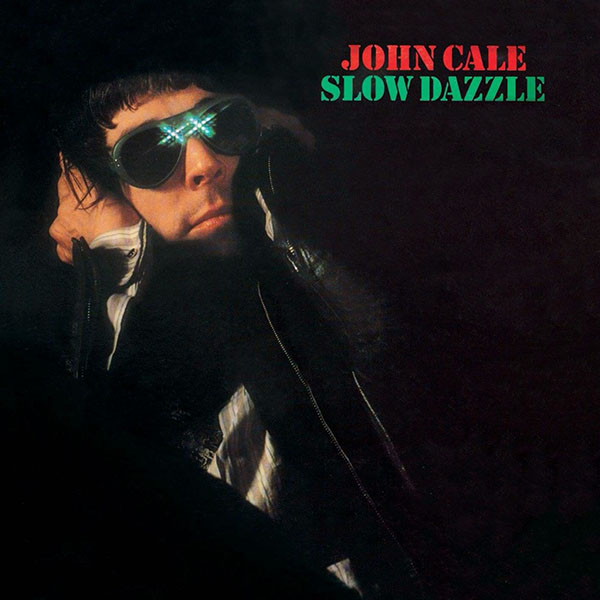

Slow Dazzle

Before that, though, let’s consider Slow Dazzle as a whole. It is, in places, a slightly lighter affair than its predecessor. Slightly. There is a more pronounced jauntiness at times, something previously hinted at by the likes of ‘Barracuda’ and ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Afford To Orgy’, but here developed into deliciously scuzzy glam; the artwork, while still largely black, is less austere than Fear and preempts the cover of Lou Reed’s abyss-circling Street Hassle (1978), while musical elements like the honking great sax on ‘Darling I Need You’ and, well, all of ‘Dirty-Ass Rock ‘n’ Roll’, engender a certain musical ribaldry that suits Cale well. But even then, lyrically, we can see that he isn’t in good shape, and it is worth noting that the only elegiac song on the record is an ornate tribute to Brian Wilson.[2]

I remember reading that Mark Lanegan once dismissed an interviewer’s probing personal questions by making it very clear that he ‘wasn’t a human interest story’, and there’s a lot to be said for that when it comes to writing about Cale. Yes, excessive drug consumption had been an integral part of Cale’s training regime for a while by this point, and yes, his marriage to Cindy Wells was in terminal, unpleasant decline, but the details of these are readily and reliably available elsewhere and I feel little need to rehash them. Suffice it to say that Cale was, in many ways, in over his head. Slow Dazzle documents an increasingly harrowing performative derangement, one which, as ever, ultimately (almost) consumes its creator, and the album offers two particularly intense examples of how this madness was transmuted into art.

‘Heartbreak Hotel’, as performed by Elvis Presley, is a lyrically dark little number, but nothing its audiences over the years couldn’t handle. There is a fine tradition of darkness, death and madness in the blues tradition, a fertile ground for the likes of Bob Dylan, Nick Cave and Jeffrey Lee Pierce. ‘Heartbreak Hotel’, as performed by John Cale, is like nothing most Elvis fans have ever heard before. It’s a lurching, howling, Grand Guignol systematic derangement of the senses. There is no trace of Elvis left[3] and there is no warning: the song starts as if in the middle of a psychotic episode, sirens blaring and a minimal bass line throbbing ominously; Cale’s vocal starts as a hiss, pre-empting the celluloid immortalisation by a fellow Welshman of a culturally refined yet spectacularly violent literary character by a couple of decades. By the time we get to the first belts of ‘feeling so lonely baby’, and the female backing vocals kick in, we’ve picked up Dracula in Memphis, and we never will get back.

Cale unleashes a primal howl towards the end of the song; again, something hinted at but never quite manifested on Fear. The Cale scream would be deployed regularly from here on, both on record and in live shows, and it is a chilling thing indeed. His live performances of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ would become especially unhinged; for instance, the footage from his 1984 Rockpalast set[4] is genuinely hard to watch, something Cale himself has himself admitted.[5] As far as musical representations of a man in a post-relationship meltdown go, it’s really quite something.

Perhaps fittingly enough, Cale debuted this cover on June 1st, 1974 at the Rainbow Theatre in London. This was essentially a showcase of some of the more outré Island artists; Cale was performing alongside Brian Eno, Nico, Robert Wyatt, Mike Oldfield and, notoriously, Kevin Ayers, with the idea being to get a live album turned around quickly and hopefully highlight that the label was concerned with more than the reggae with which it had made its name.[6] The only problem was that the night before the concert, Kevin Ayers and Cale’s wife had been getting up to shenanigans, and Cale was in full possession of the facts.

The performance of ‘Heartbreak Hotel’ as heard on the live document is gloomy and gothic and as such it perfectly leads into Nico’s take on ‘The End’; even if things are somewhat ragged, the beating of the hideous heart is very much in place. But by the time Cale was in the studio to follow up Fear, he had written a response to the Ayers episode, starting with quotidian fact then building an extrapolation of deep disillusion about the nature of mankind framed in fantasies of gory but futile revenge.

Initially, there’s no ambiguity to ‘Guts.’ When a song begins ‘the bugger in the short sleeves fucked my wife/did it quick, then split’, most of us would probably tend to sit up and take notice. And well we should, for ‘Guts’ is yet another lyrically fascinating piece where, even as the imagery quickly becomes impressionistic, it all still makes perfect sense. The 12-bore in the corner is ‘quite operatic in its self-disgust’; we have an ‘embarrassing denouement’ and ‘a familiar hyperbole’, with ‘the piss that missed the hole in the pot’ seemingly implicated. But the belligerence of the first verse gives way to the cynical epiphany later on, where ‘the waster and the wasted/get to look like one another/in the end, in the end, in the end in the end.’

The album concludes with a piece which inevitably casts our minds back to White Light/White Heat. ‘The Jeweller’, like ‘The Gift’, is a prose piece voiced in a dry monotone. However, where ‘The Gift’ has a recognisable narrative and pitch black humour, ‘The Jeweller’ is a far stranger and unsettling affair. I’m not going to attempt to summarise the ‘plot’; to do so would inevitably dilute with ridiculousness the dreamlike state it conjures. As unlikely as it seems, this piece works: conceptually it brings to mind other surrealist treatments of the erotic, such as Georges Bataille’s Story of The Eye, while the drones pulsing beneath Cale’s narration are ominous and disorientating. The prose is more dense and literary than that of ‘The Gift’, and more elusive; the more personal album thus concludes by invoking the distance of the difficult.

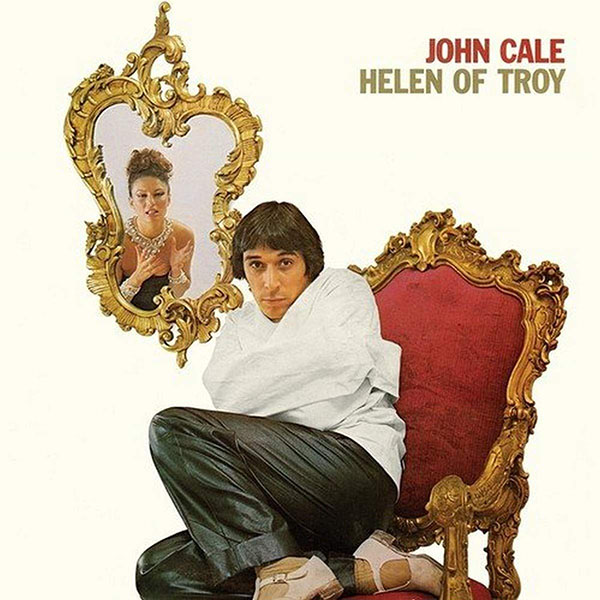

Helen Of Troy

Of the three Island recordings, Helen of Troy is the most ragged. Distracted by producing Horses for Patti Smith, as well as domestic turmoil and conflict with Island, Cale’s head was elsewhere, and it shows. The album was recorded against the clock and released before Cale considered it ready[7]. But that’s not to say it’s a bad record, by any means. The title track has remained a live staple and the studio arrangement is interesting. A mannered voice oozes homosexual lust in mumbled interjections before the first two verses and again at the end, setting up an ironic alignment between the titular beauty and the seedy NYC milieux in which Cale cut his teeth. Eno provides a trumpet flourish which adds an extra air of camp, juxtaposing the muscularity of the chorus. ‘Pablo Picasso’ lurches along on a slide guitar riff; Cale’s delivery suits the material and the arrangement isn’t hugely removed from ‘Momamma Scuba’ from Fear, though one wonders if Jonathan Richman would have preferred that the already recorded, but not yet released version by the Modern Lovers (produced by Cale) was the one first heard by the world. ‘Engine’ is a clenched-teeth descent into madness whose coda recalls the disintegration at the end of ‘Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend’, only more deliberately ‘horror’ in tone, and as such it partners well with ‘Save Us’, whose thudding toms and Vincent Price organ during the verses bring to mind no less than the early Alice Cooper band. A real curio is ‘Sudden Death’, whose plodding drums, saloon piano and scratchy guitars recall Neil Young at his darkest, specifically the album On The Beach[8].

On The Beach was released in 1974, a year before Helen of Troy, and includes a jagged, claustrophobic piece called ‘Revolution Blues’, sung from the perspective of one of the Charles Manson ‘Family’. Young was mired in death, drugs and post-fame malaise, and Manson’s assault on the values of LA perhaps seemed eerily apt. Cale makes one reference to the Manson murders on ‘Leaving It Up To You’, and it seems the invocation was enough to spook Island, who pulled the track from the album. Why did Neil Young get away with it and not Cale? Aside from Cale’s record company politics and the undisputed commercial clout Young still enjoyed, my instinct would be that Young’s piece is structured to keep a clear distinction between singer and song. Cale’s lyrics and delivery are more a demented stream of consciousness where, in places, he sounds like he is about to have a stroke; the mood is one of violent desperation and my suspicion is that the combination of fragmented images of death, dissolution, war, media sensationalism, and how ‘we could all feel safe like Sharon Tate’ probably made the suits at Island more than a little bit uneasy. Live, the song became another failed catharsis, Cale screaming himself hoarse both in character and not, adding more layers of psychosis to an already deeply unhealthy melodrama[9].

One of my great concert disappointments came in early 2007 when I saw Cale play The Village in Dublin. I was very close to the front and the set was very good, but about halfway through Cale was visibly incensed when a drunk member of the audience managed to place a pint of Guinness at his feet as he was playing keyboards. Cale, a long-reformed character, gestured furiously to the stage security to remove the drink, only for the same thing to happen again about ten minutes later, at which point the punter was removed. This added a new layer of intensity to proceedings – at one point I caught Cale’s eye and as he stared me down it felt like the fucking devil was glaring into my soul – but the downside was that he didn’t play the second encore. I could see the setlists taped to the stage; it would have been ‘Leaving It Up To You.’ The proposed original title for Slow Dazzle seems apt: Bugger.

Key Works

Fear, Slow Dazzle and Helen of Troy are readily available as individual titles. They also comprise a double-CD compilation entitled John Cale: The Island Years.

Two indispensable written resources:

Tim Mitchell. Sedition and Alchemy. London: Peter Owen, 2003.

Fear Is A Man’s Best Friend (Est. 1999) is the ultimate unofficial John Cale website

Worth having:

Peter Hogan. The Rough Guide To The Velvet Underground. London: Rough Guides, 2007.

And, if you’re feeling very flush….

John Cale and Victor Bokris. What’s Welsh For Zen? London: Bloomsbury, 2000.

(I have read it, once, years ago, and have never owned it. Open to donations, etc.)

Essential Viewing:

Gareth lurks on Twitter as morebarn https://twitter.com/herbmanhustling

*

Stay tuned for the next installment:

JOHN CALE IN THE 70s

Part Two: I Can’t Keep Living Like This No More.

[1] Otherwise unavailable aside from the opening track, ‘Mercenaries (Ready For War)’, a studio version of which was released as a single in 1980, backed by ‘Rosegarden Funeral of Sores’, later covered by those other gaunt-cheeked masters of chiaroscuro, Bauhaus.

[2] The chorus of this song is a masterclass in metre: ‘And you know it’s true/That Wales is not like Californ-i-a in any way’ is just wonderful.

[3] The King died two years or so after this was released. I’d love to know if he heard it, and what he thought.

[4] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jrZH9FDhfRs

[5] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SbIDJ7lNHik

[6] https://www.moredarkthanshark.org/eno_int_ulclasroc-jun14.html

[7] https://werksman.home.xs4all.nl/cale/disc/helen_of_troy.html

[8] One of those songs where Eno gets a turn and you wish he didn’t because he spoils the mood with his messing around.

- Music

- 1970s, Alice Cooper, Bob Dylan, Brian Eno, Brian Wilson, CBGB, Charles Manson, Cindy Wells, Elvis Presley, Gareth Wilson, Georges Bataille, Island Records, Jeffrey Lee Pierce, John Cale, Jonathan Richman, Kevin Ayers, Lee Pierce, lou reed, Mark Lanegan, Mike Oldfield, Modern Lovers, Neil Young, Nick Cave, Nico, Pablo Picasso, Phil Manzanera, Robert Wyatt, Rockpalast, Velvet Underground

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress