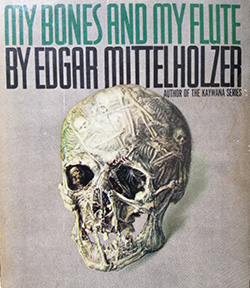

My Bones and My Flute: Remembering Edgar Mittelholzer

Potty Paul

At age 16 I took the ferry with my schoolfriend Paul to the Isle of Man for a holiday. We had met years ago in the Infants; he called me Dave, I called him Potty and that was all it took to cement a friendship. The Isle of Man was a celebration of the fact that school was now over. It was our first holiday without adult supervision, and I remember it as a long list of daft antics and adventure from one end of the small island to the other. We couldn’t know at the time, but it would also be a sort of farewell salute to childhood and our friendship. We never really hung out after that. Free of the confines of school there didn’t seem much point anymore and I sensed we had a lot less in common without it.

This was the summer of 1976, the second hottest summer on British record, and we wore matching floppy denim hats to combat the likelihood of sunburn. We looked daft but at 16 that’s often the point. Ultimately my hat failed me, and I suffered a red nose for two weeks.

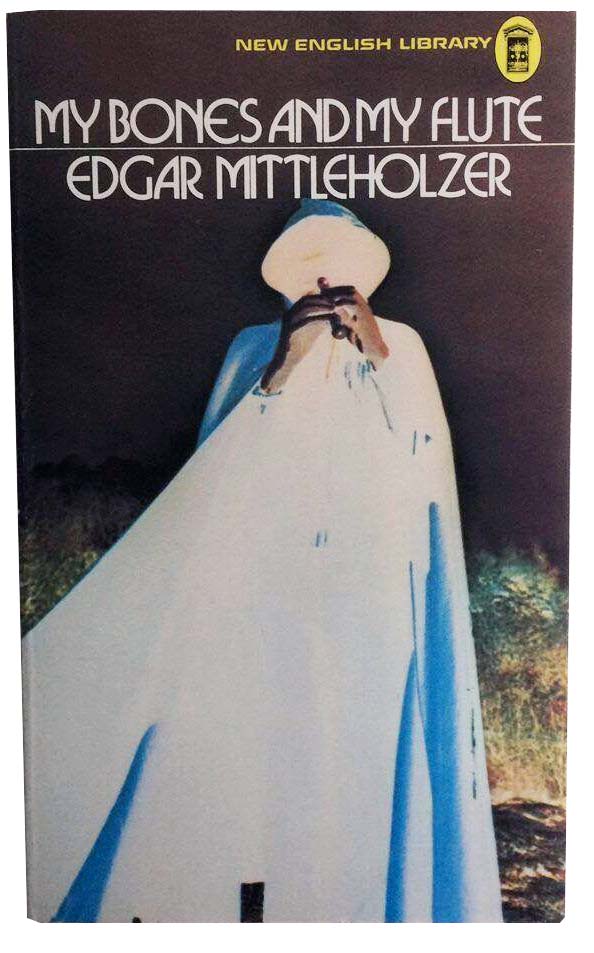

There is something else I remember about that holiday. In a newsagent shop in Douglas, the Isle of Man capital, was a book stand filled with cheap paperback novels, among them My Bones and My Flute by Edgar Mittelholzer. I had read the supernatural tale only recently, a library hardback and had enjoyed it, and so toyed with the idea of buying a copy for myself. But there was no place for books on an Isle of Man expedition and it was much too hot for it anyway. I recall more than one copy of My Bones and My Flute on the rack, many copies in fact, all at cut-price. Perhaps its dreary mood and remote Guyana plantation setting was off-putting to holiday readers in Douglas.

Mittelholzer’s novel has a strange, dense atmosphere, one that has stuck with me over the years. It is inextricably entwined with the Isle of Man, fond memories of Potty Paul, and the seemingly endless cycle of synapse-popping that comes when childhood is invoked: through one thing another is remembered.

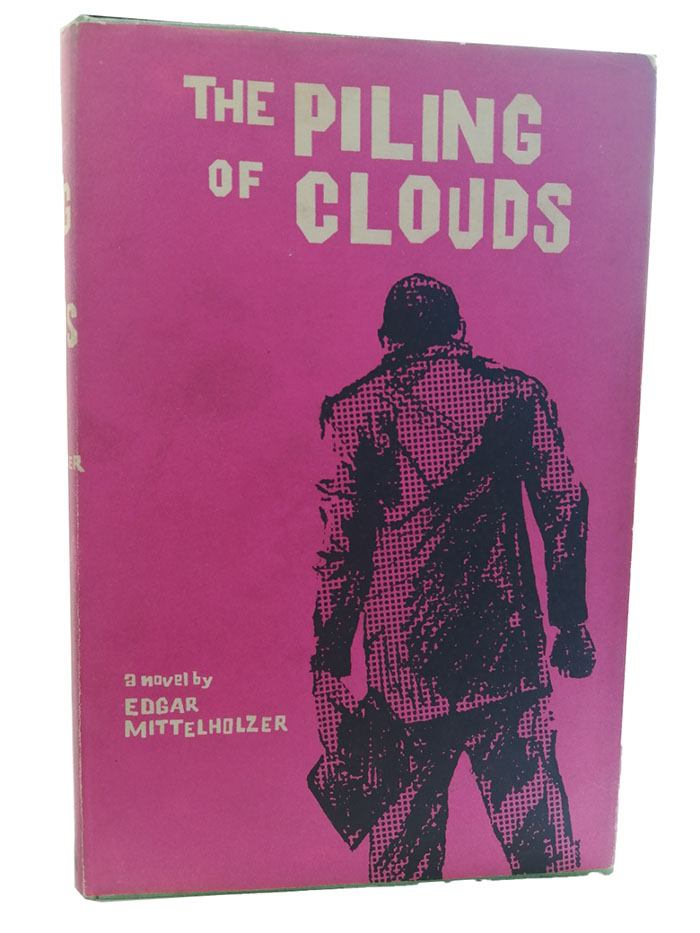

I was not aware that Mittelholzer had written any other books until I chanced upon The Piling of Clouds about two years ago in an Oxfam bookshop. It was a first edition published in 1961. The title piqued my interest — a strange title — but then, having browsed enough bookshops, one gets an innate sense of a book that is not like others.

Chris

The jacket was purple with a simple drawing of a man facing away, into nothingness. A picture of Mittelholzer on the inside back flap simply described him as The Author. A bibliography near the front, however, listed My Bones and My Flute as one of his other works.

Until a few weeks ago I knew next to nothing about Mittelholzer. Sometimes I forget that Google exists and often I don’t want to know what Google might say in any case, preferring to glean knowledge elsewhere in its own good time, as if knowledge is a certain room that opens when ready. I discovered a lot about Edgar Mittelholzer in the most recent issue of Biblio-Curiosa (No 10), courtesy of author-publisher Chris Mikul’s article ‘Going Into The Dark: The Life, Death and Work of Edgar Mittelholzer’ — not least that Mittelholzer was born in Guyana, wrote in many genres, was interested in meteorology, unsuccessfully tried to introduce a new technique to novel writing, and died horribly.

Edgar

Of the many books that Chris had read while researching Mittelholzer, The Piling of Clouds was evidently not one of them. He later told me that he hadn’t been able to locate a copy of it, in response to an email, in which I wrote:

“The Piling of Clouds is certainly odd, perhaps one of the most curious novels I have read. I don’t know if you have read it but — spoiler alert — the story on the surface is a lot like Lolita, in that a paedophile living in a London suburb inveigles his way into the family next door to be near their young daughter. They end up going on holiday together, but this hardly seems to be Mittelholzer’s point, and at times I felt he had ‘forgotten’ this dimension of the plot entirely. The father rabbits on about society’s failings at every opportunity, “Human Vermin” and “Would-rotters” (liberals for the most part) so that the book reads a lot like a manifesto. Having read your Biblio-Curiosa piece, I now understand this is very much Mittelholzer. What surprised me most about the book were the references to novelist and philosopher Colin Wilson, who pops up as a subject for debate not once but several times throughout the novel! These passages are shoehorned-in and impossible to read without picturing Mittelholzer on a soap box and the ‘real’ purpose of the book as a ‘response’ to Wilson and his populist ideas. (Colin Wilson’s 1960 serial killer novel, Ritual in the Dark, inspires a tirade about “Anti-Bomb people” and their ilk over several pages.)

“The ending takes another twist, and the novel is surprisingly sympathetic toward the paedophile, portrayed throughout as a troubled individual but one who is battling to control his criminal desires. The father, on the other hand, comes across as a boor and ultimately proves to be something of a weak-willed hypocrite.

“As I say, an odd book.”

Coda

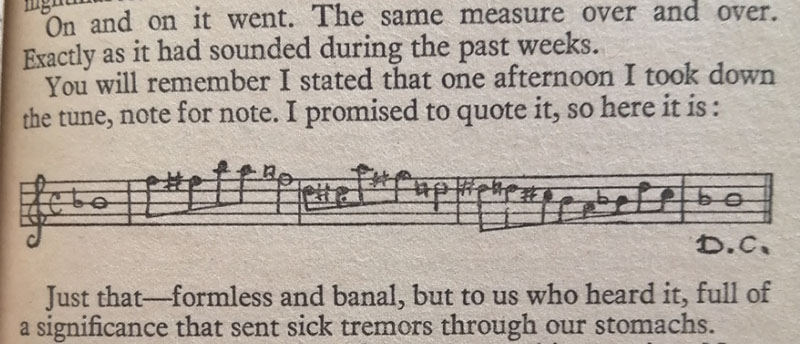

A phantom melody is heard throughout My Bones and My Flute, the sound of a flute playing a haunting refrain often accompanied by an unpleasant smell. Towards the end of the book, the melody appears in notation form.

Chris kindly supplied a recording. He says in one email: “We were down in Melbourne last weekend and caught up with our friend Leonie who plays the flute. I got her to play the flute tune in My Bones (as you may remember, Mittelholzer included the notation in the book) and I recorded it.

“She went off to practise it as she was playing it and the sound came out though the back door — I was floored.”

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress