Teresa’s Records

“I don’t dig chicks like you!”

This is what ‘Dickie’, the brutish gangster at the heart of Roman Polanski’s 1963 black comedy Cul-de-Sac, tells Teresa. He and his dying partner-in-crime Albert have taken refuge on the remote Northumberland island where Teresa lives with her husband George.

Played by Françoise Dorléac, Teresa is a free spirit and Dickie’s rebuke is just one of a series of insults she has to endure during the film. At one point, George, siding with Dickie in a cowardly attempt at male bonding, describes Teresa as “a very naughty girl”. Later, Horace, the brattish child of George’s visiting friends, calls Teresa a “froggy bitch”; this after she has painfully twisted his ear because he has mistreated her records.

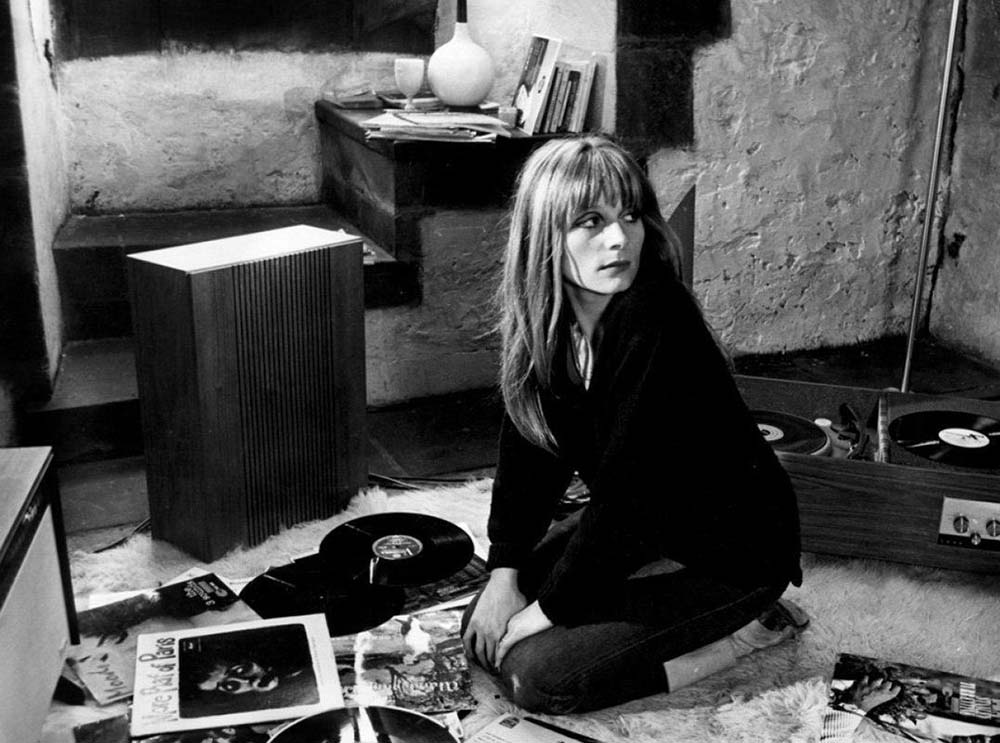

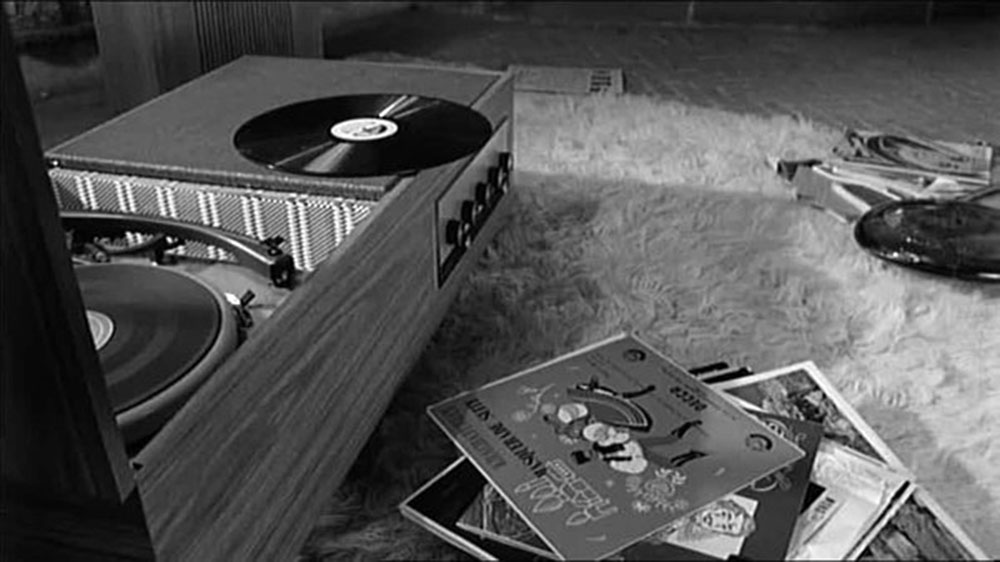

Teresa’s records are very important to her. We see them scattered on the fur rug and around her groovy music system.

Bullies and Captors

Her records are an expression of her freedom in the face of dour isolated surroundings and a stifling glut of repressive male egos. Most films of this period, directed by men, use female characters as vacuous ciphers for male fantasy, insecurity, and confusion. Polanski’s early films, while excellent, are no exception to this. His films feature neurotic women who are fragile and tormented, such as Carol in Repulsion (played by Dorléac’s sister, Catherine Deneuve) descending into madness and murder as a result of the dark oppression of her surroundings, or Rosemary, in Rosemary’s Baby, who is forced to give birth to the child of Satan. But sometimes, as with Teresa in Cul-de-Sac, the women break out and defy their bullies and captors.

Walk on the Water

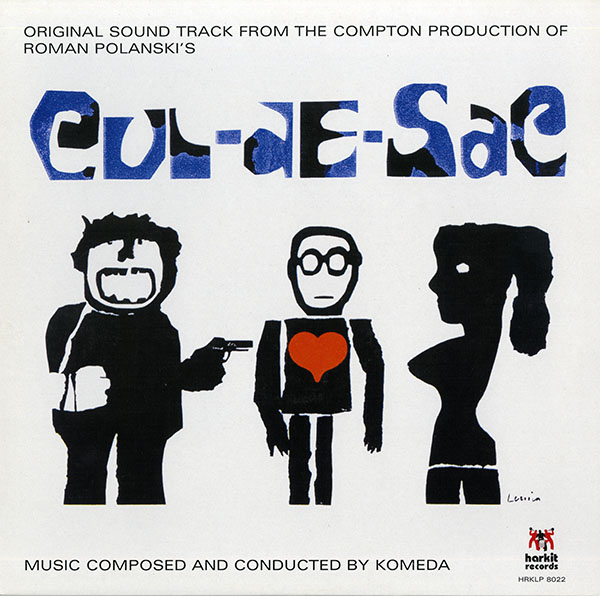

Due presumably to the vagaries (and huge expense) of music licensing, we never get to hear Teresa’s record collection in Cul-de-Sac. When Teresa plays a recording in the film what we actually hear is the brilliant score created by Krzysztof Komeda. Komeda’s haunting waltz ‘Walk on the Water’ recurs throughout the film as the sound of one of Teresa’s discs.

Despite this, close examination of the records that Teresa plays reveals she has excellent bohemian tastes, not at all interested in the stereotypical kind of bland commercial pop music normally attributed to young women in films. While Teresa’s collection does include classical LPs such as Khachaturian’s ‘Masquerade Suite’, the cover of which we catch a glimpse of, she is a fan of much cooler sounds.

Blues Theme

To Teresa’s left is tenor saxophone player Stanley Turrentine’s 1961 Blue Note LP Dearly Beloved, a set of bluesy soul-jazz tunes. Appropriately, the electric organ on the LP is played by ‘Little Miss Scott’ AKA Shirley Scott (Turrentine’s wife at the time) a rare instance of a female musician featuring on a jazz LP of this era. Despite Turrentine’s playing initially being treated with indifference (‘meat and potatoes blowing’[1]), soon after his work was being hailed as ‘soulful’ when compared to the unpleasant avant-garde sounds then in circulation. Teresa owns another LP on the Blue Note label, Moods by The Three Sounds, one of the successful piano trios then in vogue who played what could be called ‘smart background music’.[2] The cover features a startling close-up of a woman’s ecstatic face, reminiscent of Bernini’s 15th century sculpture ‘Ecstasy of Saint Teresa’, a state we imagine our film Teresa is desperately searching.

The blues theme, redolent of Teresa’s general mood on the island, is reflected in her ownership of a UK HMV pressing of a ‘Greatest Hits’ LP by rhythm and blues legend Ray Charles, exactly the kind of raw African American expression that would offend the sensibilities of her husband and his snobby friends. Indeed, George yells at her to “Cut that music!”, his pomposity and conservatism always getting the better of him. Mark Cousins describes Polanski’s central theme as an exploration of ‘human claustrophobia and unease’;[3] it is this that Teresa must escape from, even if only psychologically.

The Wrong Speed

Teresa’s defiant ‘Frenchness’ is reflected in her ownership of an LP of songs by legendary chanteuse Edith Piaf. More Piaf of Paris is an Anglo-Saxon presentation of the art of the ‘little bird’. A non-conformist like Teresa, who poses in the mirror with a bottle of booze and wet hair before playing her records and setting fire to Dickie’s feet, finds in the ‘high priestess of agony’ a kindred spirit, one heartily sick of men and their idiocy, yet still drawn to aspects of their character. The records chosen by Polanski and his team for Teresa could have been selected randomly. However, they do symbolise a varied taste that is in keeping with the groovy times and which only Teresa properly represents in the film.

This music follows Teresa around the castle, acting as an escape from the leaden skies that loom over it, indicative of the oppressive settings and mysterious geography evident throughout Polanski’s ‘isolation trilogy’ (Repulsion, Cul-de-Sac, The Tenant). Horace’s terrible crime is to play Teresa’s records at the wrong speed and this enrages her into action. Later, Teresa puts on a record only to hear it stick on repeat due to the damage that Horace has inflicted on it. David Thompson calls this repetition a symbol of the way in which the film’s characters are ‘imprisoned in a circle defined by the shores of an island’.[4] Following the realisation of the damaged records, Teresa picks up the shotgun left by Cecil (another of George’s insufferable friends who Teresa, despite this, takes a shine to) and, given her husband’s ineffectiveness, decides to ‘take matters into her own hands’…

Françoise Dorléac died in a horrific car accident on 26 June 1967 aged 25. She was en route to Nice Airport and lost control of her vehicle which flipped over and burst into flames. In Cul-de-Sac Teresa smokes, drinks vodka, and digs graves. Ultimately, she is the only character in the film with any honesty and authenticity. Teresa symbolises liberation and her records act as a powerful symbol of this rebellious tendency.

Notes

[1] Richard Cook, Blue Note Records: The Biography. London: Pimlico, 2003.

[2] Cook, p.123.

[3] Mark Cousin, ‘Polanski’s Fourth Wall Aesthetic’, in The Cinema of Roman Polanski: Dark Spaces of the World, edited by John Orr and Elżbieta Ostrowska. London: Wallflower Press, 2006, p.3.

[4] David Thompson, ‘High Tides’, Cul-de-Sac (DVD). Criterion, 2017.

Mark Goodall

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress