Your Friend Of The Mists…

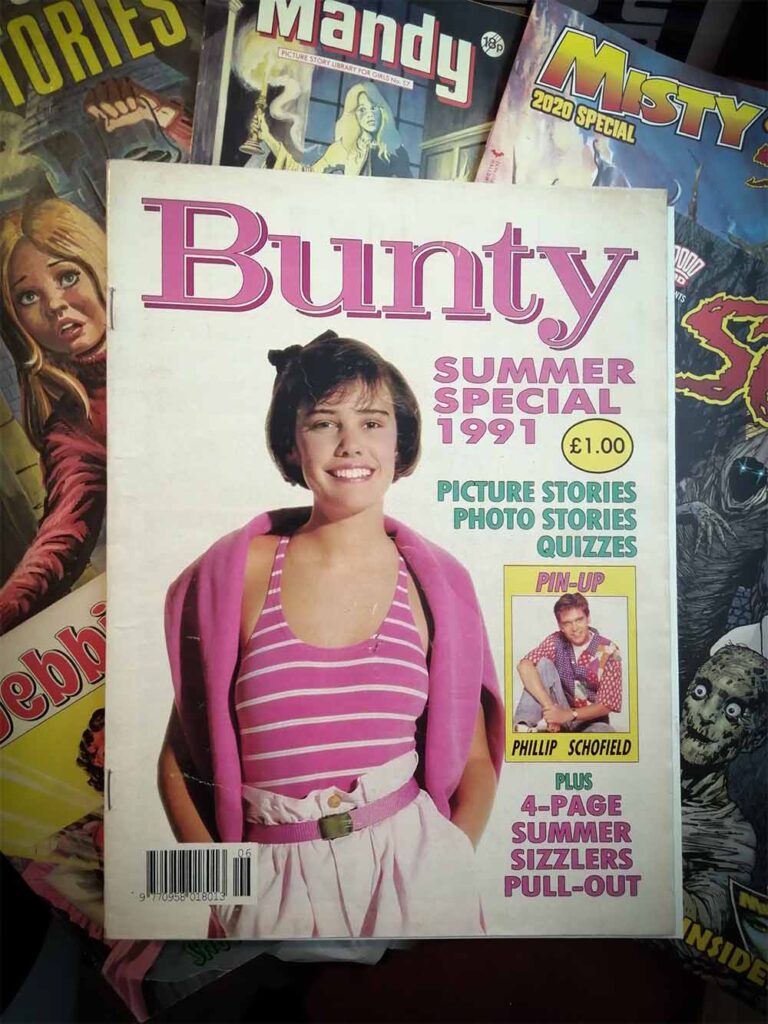

I HAVE A VIVID MEMORY of my first encounter with girls comic Bunty. It was the summer of 1991 and we were midway through our usual annual family holiday to Flamborough on the Yorkshire coast. The Bunty Summer Special was on the shelves of the newspaper and ice cream kiosk at the top of North Landing’s cliffs, and for the princely sum of £1 it was mine. Whenever I look at that Summer Special — re-purchased years later from eBay at a 3,300% cost increase — it’s inseparable from memories of a beige and white caravan, tie-dyed denim shorts, and a pair of purple jelly shoes.

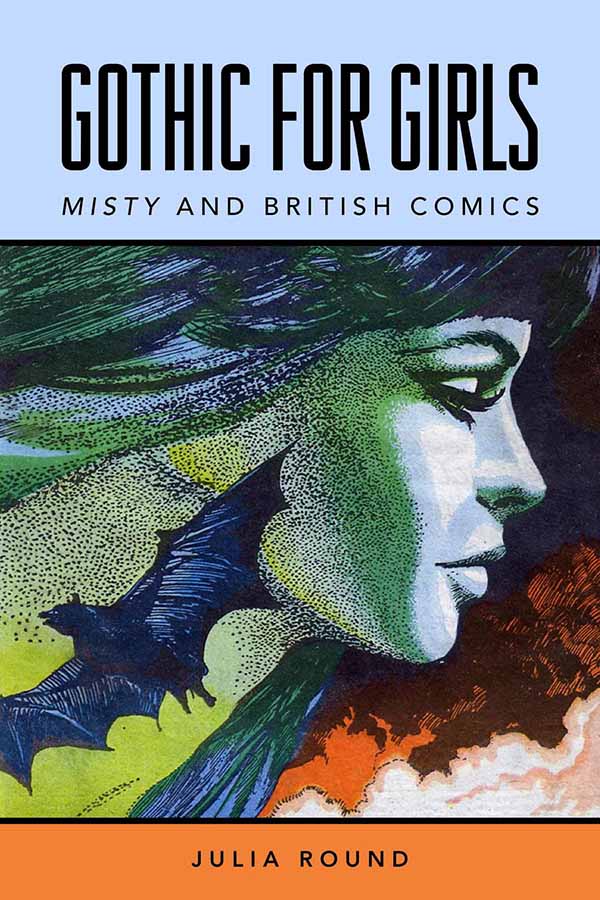

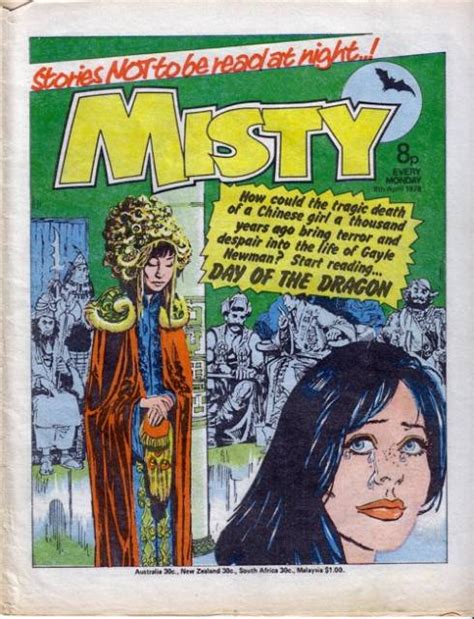

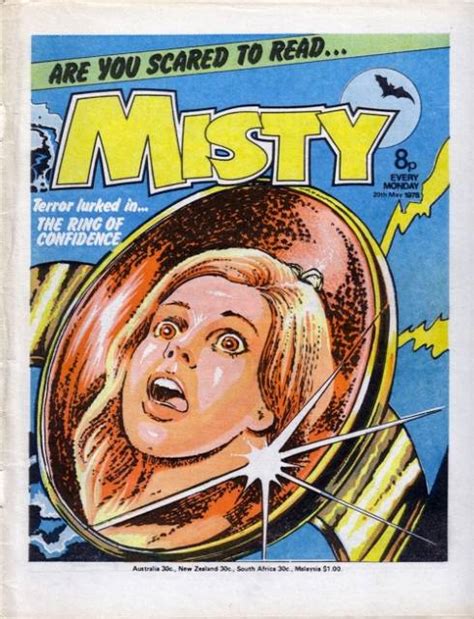

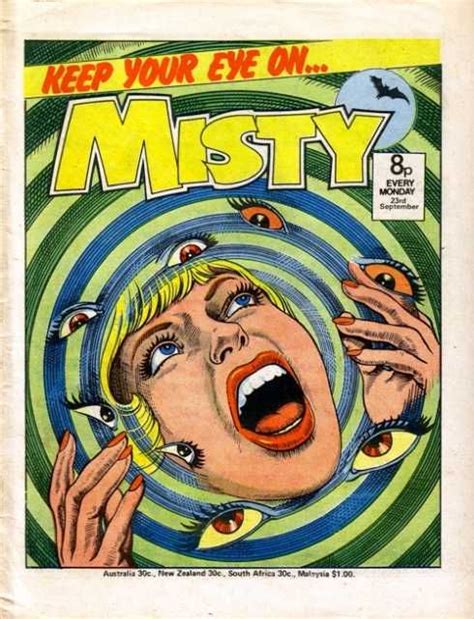

This is perhaps what David Moloney alludes to when he says that ‘these favorite artifacts of our childhood are important to us on a very personal level. They’re like religious relics’. Moloney is speaking here to Julia Round, whose Gothic for Girls: Misty™ and British Comics (2019) is the outcome of her own quasi-religious quest to find a relic from her childhood. For years she had a memory of a comic strip that terrified her as a child: the story of a young girl given a magic mirror that will make her beautiful. In true cautionary tale style, the girl becomes more and more unpleasant the prettier she becomes, eventually finding herself stuck with a horrifically disfigured face when the mirror shatters. The story ends with a direct question to the reader: ‘How would you like to wake up every day … like this?’ The story that Round was remembering was ‘Mirror … Mirror’, published in Misty in 1978; her memories of it, and journey to discover more about it, open Gothic for Girls. The book’s aims are twofold: to offer a full-length critical study of British girl’s comic Misty, and to argue for a distinct but undertheorized subgenre of the Gothic: Gothic for Girls.

Lucky Black Cat Ring

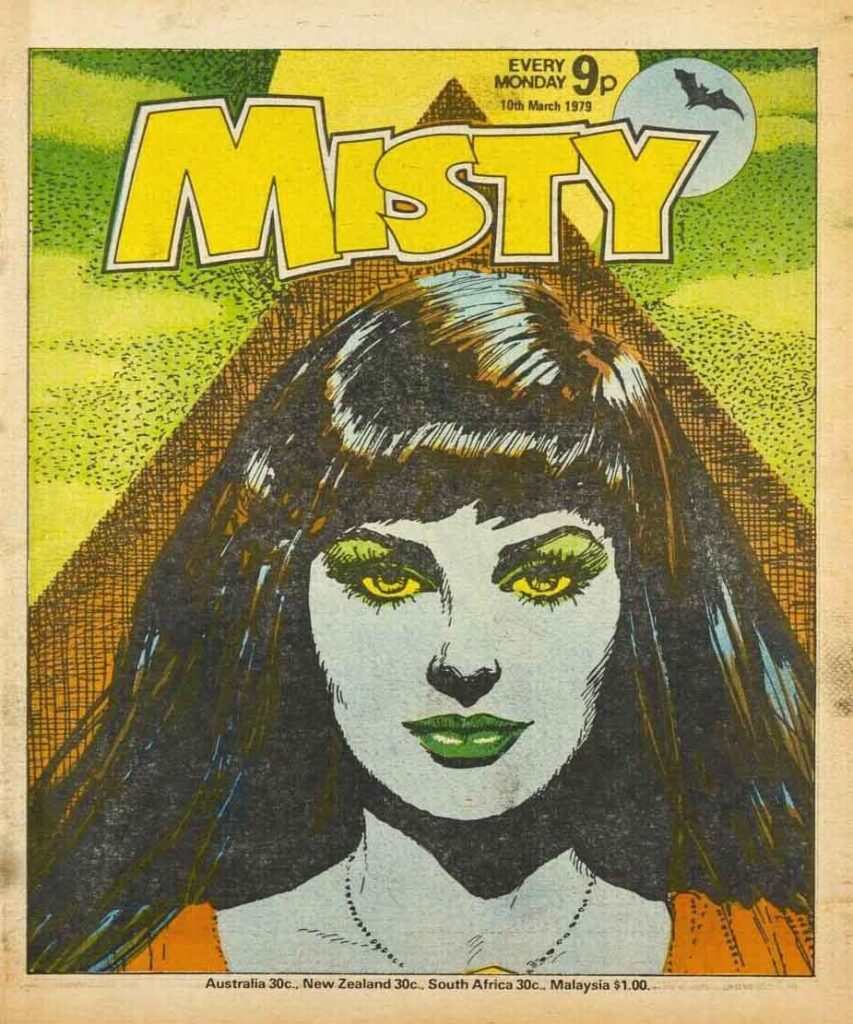

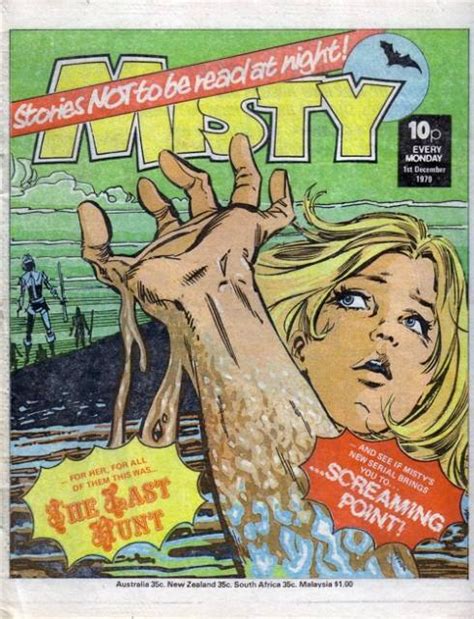

Misty, first appearing on newsagents’ shelves in early 1978, was one of many girls’ comics in Britain in the mid to late 20th century. Girls’ comics frequently outsold boys’, but by the 1970s their popularity was being challenged by magazines for women and teens. A ‘new wave’ of girls’ comics in the 1970s, including Tammy and Jinty, revived the genre, but titles like Spellbound and Misty went further: foregrounding supernatural and mystery stories. Round offers a fascinating account of Misty’s origins, including the inspiration behind the comic’s name and the broader cultural influences that shaped some of its most notorious stories — such as ‘The Sentinels’, set in a dystopian future where the Nazis won WWII. Marketing was canny; as often with British comics, free gifts accompanied the early issues, here linked to the stories within: a ‘Lucky Black Cat Ring’ complemented ‘The Cult of the Cat’ in Misty #2.

Most interesting for me was Round’s detailed account of artists and writers involved with the comic, who are so often uncredited and left out of comics histories. Artists and writers rarely got a fair deal from big publishers like IPC who published Misty; they were forbidden from signing their work and rarely allowed to keep originals of their artwork. Some writers and artists got around these restrictions by sneaking their names into the background of panels, via a newspaper headline or book spine (matters would improve after 2000AD introduced credits under Kevin O’Neill and other comics began to follow suit). A chapter on Spanish artists highlights the crucial role of Spanish agencies in the development of British comics (an interesting counterpoint to the adult orientated horror comics in the US published by Skywald and Warren), and there are informative biographies of key players in the Misty universe, including glamorous portrait artist Shirley Bellwood who modelled cover girl/horror host Misty on herself. Unusual for a book from an academic press, and most welcome, are the wealth of colour illustrations showcasing the talent behind Misty but also presenting an original strip that dramatizes Round’s own research journey, written by Round and drawn by Letty Wilson.

Topical Issues

In later chapters, Round undertakes in-depth analysis of Misty’s content, quantifying design features, plot types, and Gothic symbolism. This quantitative, technical, approach can be a little laborious and list-like — at some points, glimpses of Round’s working database are even included as illustrations — but it is nevertheless a persuasive way of confirming the innovation that was at work in Misty. With few recurring characters in each issue, Misty perhaps offered more possibilities for readers to personally identify with characters (a feature that also unfortunately allowed for Misty’s own distinctive identity to be lost when the comic merged with Tammy in 1980). Misty engaged with topical issues, especially environmental concerns and animal rights, and often pointed readers towards adult Gothic fare such as the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. Several stories adapted films of the time (‘Moonchild’ was a version of Carrie, ‘Hush, Hush, Sweet Rachel’ a riff on Audrey Rose), and the frequently out-of-proportion punishment for character’s minor transgressions fitted perfectly alongside public information scare films of the 70s.

Uncanny Experience

At the same time, Round clearly articulates how Misty drew upon much older Gothic traditions that emphasise transgression, transformation, and Otherness — themes that resonated with many girl readers. The popularity of the Gothic in children’s and YA literature — from Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden (1911), to Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising (1973), to the 1990s cult phenomenon of Point Horror — is especially pronounced when looking at adolescent female readers. This is where Misty fits, argues Round: ‘Gothic for Girls constructs and acknowledges girlhood as an uncanny experience’. That Misty’s approach and tone resonated with readers is demonstrated in a chapter on the comic’s letters page, where readers formed a community that transgressed boundaries of gender, age, and location. Although articulating a particular kind of ‘Gothic for Girls’, Misty’s appeal was clearly much wider, and has become even more so in recent years with retrospective collections such as Rebellion’s Jordi Badia Romero Collection and the Scream! & Misty collaborations. The last issue of the original Misty was published in January 1980, yet its impact was significant enough for fans such as Chris Lillyman to set up sites and fanzines dedicated to it twenty years later. As Round notes in her conclusion: ‘The demise of the British comics industry is a sad result of the lack of value placed not just on its creators but also on childhood agency’. Gothic for Girls is a fascinating, in-depth account of just one British comic that made its mark on our childhood consciousness, and I hope it will be followed by many more such accounts that explore their subjects with as much passion as Round has done here.

- Reviews: Books

- 1970s, 2000AD, Audrey Rose, British Comics, Bunty, Carrie, Chris Lillyman, David Moloney, Edgar Allan Poe, Frances Hodgson Burnett, gothic, Gothic For Girls, IPC, Jennifer Wallis, Jinty, Julia Round, Kevin O’Neill, Misty, Point Horror, public information films, Scream, Shirley Bellwood, Skywald, Spellbound, Susan Cooper, Tammy, Warren

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress