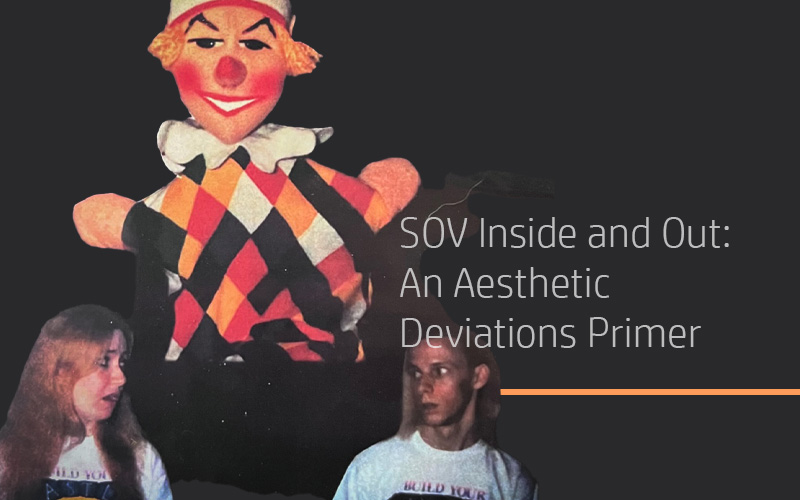

SOV Inside and Out: An Aesthetic Deviations Primer

WHILE SHOT-ON-VIDEO (SOV) horror has grown in popularity in recent years and attracted a spate of new devotees, there’s still plenty of room to introduce wider audiences to this niche corner of independent film history. Essential titles from the cycle such as Video Violence, Splatter Farm, Blood Cult and Black Devil Doll from Hell have been canonized by alternative cinema fanatics and hold their own in discussions of cult genre films from the 1980s. Beyond these are a wealth of obscurities that prove equally worth one’s time, whether as genuine revelations or just pleasant diversions. While my own work pinpoints a sort of golden era between 1984–1994, in truth SOV horror extended far beyond this window, maintaining underground commercial viability well into the early 2000s and beyond. The once aberrant nature of SOV horror is harder to contextualize in the present day when even multi-million-dollar Hollywood epics are largely shot on advanced digital video technology. In fact, nearly every horror film one can see — whether it be Hereditary or the Insidious series — are in effect shot-on-video features themselves. In many ways, SOV horror, once considered a malignant outgrowth of respectable cinematic creation, has become the accepted reality of today’s digital filmmaking landscape.

I won’t bore with the technical details that differentiate analog from digital video. What I will say is that a large part of the allure in analog SOV features is their tangible quality, the bizarre yet familiar look of the supposedly unpolished format. Analog video has long been derided as unprofessional, be it the broadcast quality dreaminess of soap operas, or the more immediate nostalgic conjuring of family home movies shot with a cheap camcorder. In fact, I sincerely believe that SOV horror’s proximity to home video recordings, unpolished and unintentional verité in several regards, is one of its many notable attributes. By the same token, a great deal of inept SOV features bear the melodramatic tone and pacing of soap operas — take a look at the middle sections of Blood Cult’s campus slasher hijinks, or the longer features from New Jersey’s W.A.V.E. Productions. Where SOV horror was once taken to be utterly disposable by virtue of its format alone, retrospective reappraisals position this amateurish presentation as one of the key elements worth evaluating.

For my own purposes, SOV horror refers to features shot on analog video cassettes, often by amateur or at least independent filmmakers outside the circles of commercial cinematic production. Of course, in its earliest days, SOV horror was inextricable from the workings of commercial moviemaking, as the video store boom of the 1980s and growing affordability of VHS and VCR technologies necessitated a greater demand for product than major studios could meet. As a result, various regional productions by aspiring auteurs found their way into stores across the country, placed on shelves to be rented alongside the latest films by George Romero, John Carpenter, and myriad slasher sequels. These are primarily the titles that remain familiar to audiences, their availability and commercial success defining the trend that was to follow. As the 1980s progressed, and particularly into the early-1990s, SOV horror was left out of the video store equation for several reasons. Customers expecting a traditional horror film were disappointed with the pugnacious video releases that they found themselves renting, and made their displeasure known. Thus, stores were less likely to buy SOV product, something that coincided with the rise of Blockbuster Video and other chain stores that monopolized the rental industry. Only independent stores were likely to take risks on SOV releases, albeit in smaller quantities than in years prior, and enterprising filmmakers were forced further underground to self-distribute and rely on a small network of independent video labels. This is the starting point for the underground horror film scene of today, an indirect lineage that speaks to the truest and widest ranging impact of the initial SOV cycle on film culture.

I should point out that SOV horror should be differentiated from the similarly low-profile super 8 genre films produced during the 1980s and 1990s. The obvious difference being that the latter is an actual celluloid format rather than magnetic tape. However, super 8 served as a testing ground for several of the auteurs discussed in Aesthetic Deviations, including the Polonia brothers, Carl Sukenick, and Todd Sheets. SOV mainstay J.R. Bookwalter even lensed his first feature film, 1988’s The Dead Next Door entirely on super 8 with an astonishing budget of $125,000. So consider the wave of amateur films produced during this period by artists like Nathan Schiff, Tim Ritter, and Leif Jonker to be an entirely separate category of work, though possessed of the same driving spirit as SOV horror.

Below are some of the key filmic and textual resources employed in writing Aesthetic Deviations as a sampler for those curious to investigate the cycle of filmmaking further. Consider these entry points into the world of SOV horror, as well as the fanzine underground and even the critical theoretical realm that influenced my own writing process.

MOVIES

Black Devil Doll from Hell — One of the first SOV titles to gain infamy on the nascent home video market, and for decades to come the standard-bearer of the cycle’s infamy. Look past all the jabs taken in fanzines and online and Chester N. Turner’s debut stands out as a significant development in several ways. It was one of the first SOV titles to be produced by an amateur creator and self-distributed, and remains (along with Turner’s 1987 follow up Tales from the Quadead Zone) one of the only video efforts of the 1980s to be produced with a mostly-African American cast and crew. None of this is to say that its notoriety isn’t earned, as BDDfH is still risible almost forty years after its creation, playing as a simple morality tale drenched in base misogyny and cheap titillation. There is also, of course, endless tedium throughout the film’s seventy-minute runtime, imparting a strange tension between its more risible excesses and indulgent stasis. An essential experience to understand just what makes SOV horror cinema tick.

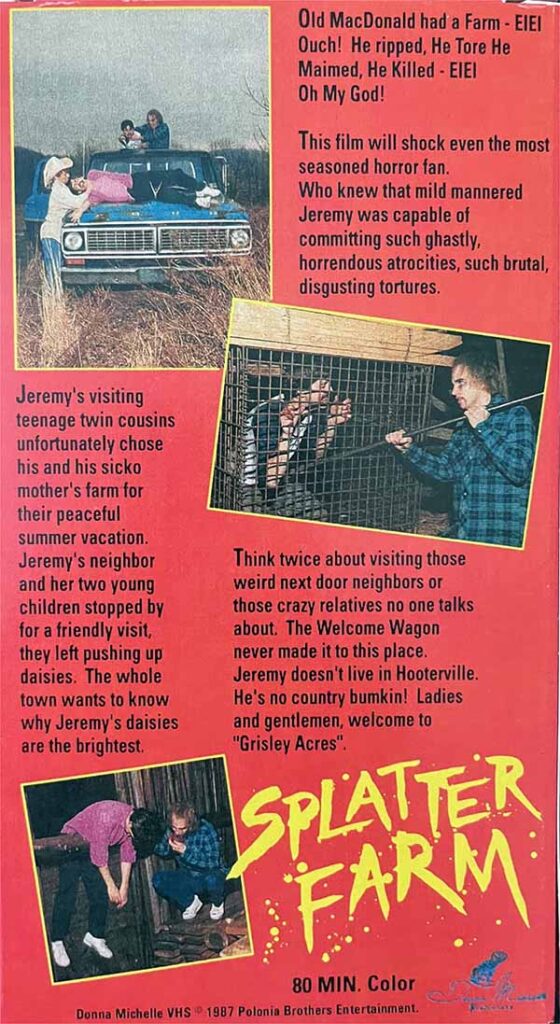

Splatter Farm — Perhaps the quintessential example of the teenage SOV film, and one that against all odds saw widespread release thanks to Donna Michelle’s distribution. Twin brothers Mark and John Polonia cut their teeth making countless super 8 shorts and features throughout their adolescence, imitating their favorite horror titles while adding a strong dollop of suburban Pennsylvania weirdness. After two attempts at video features, Church of the Damned and Hallucinations (unreleased until the 2010s), and an unsuccessful move to California to jumpstart their careers, the brothers hunkered down and produced their 1987 masterpiece over one summer. Infamous for its quotient of perverse gore effects, aberrant homoerotic debauchery, and its inexhaustible cavalcade of horrors, Splatter Farm is a landmark in adolescent filmmaking. Still, it proved to be just what the Polonias were after and allowed them to embark on a long independent filmmaking career, which Mark has continued since John’s untimely passing in 2008.

Red Spirit Lake — One of my favorite SOV releases, Charles Pinion’s 1993 follow-up to his skatepunk splatter headtrip, Twisted Issues, is his masterpiece. A work more firmly rooted in the real world and investigating the consequences of gendered violence and the oppressive and omnipresent threats women face throughout history and every space they inhabit. Bringing both a more experimental style, as well as excruciating levels of violence, Pinion’s second feature is one of the most thought-provoking SOV works of any era. Pinion also makes impressive use of the titular exterior setting, an upstate New York vista covered in a thick blanket of snow for the entirety of the film. By contrasting this setting with his stylishly lit interior spaces, Pinion ensures that Red Spirit Lake transcends the regional fascinations of most SOV productions and emerges into the world fully formed, its strange and unsettling visions so effective because they present themselves within a realm so recognizably our own yet also estranged by the jarring grittiness of his format.

Goblin — Todd Sheets’ 1993 release may not be my favorite of his films, but it does stand out among his filmography as a particular sort of bad taste landmark. Built on the typically sturdy premise of cursed items in a newly purchased farmhouse arousing the malevolent title creature, this frame is little more than an excuse for excessive bloodletting of the crudest variety. Genital mutilation, organs pulled from anuses, and various sputters of watery blood fill the screen for extended stretches of the runtime. These low/high points are tempered with painfully 90s fashion and hair, as well as endless wandering in and outside of the protagonists’ house. Still, Sheets delivers something more than the sum of its part, as the nighttime videography and desolate rural setting do manage to add a touch of atmosphere that enhances the low production values. Somehow, Goblin seems a perfect place for initiates to Sheets’ unique style to begin.

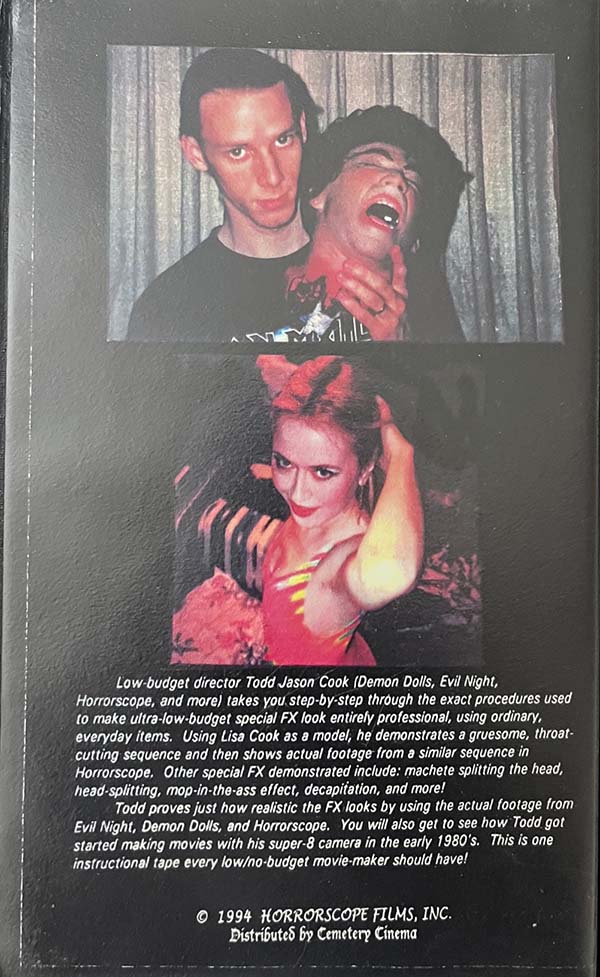

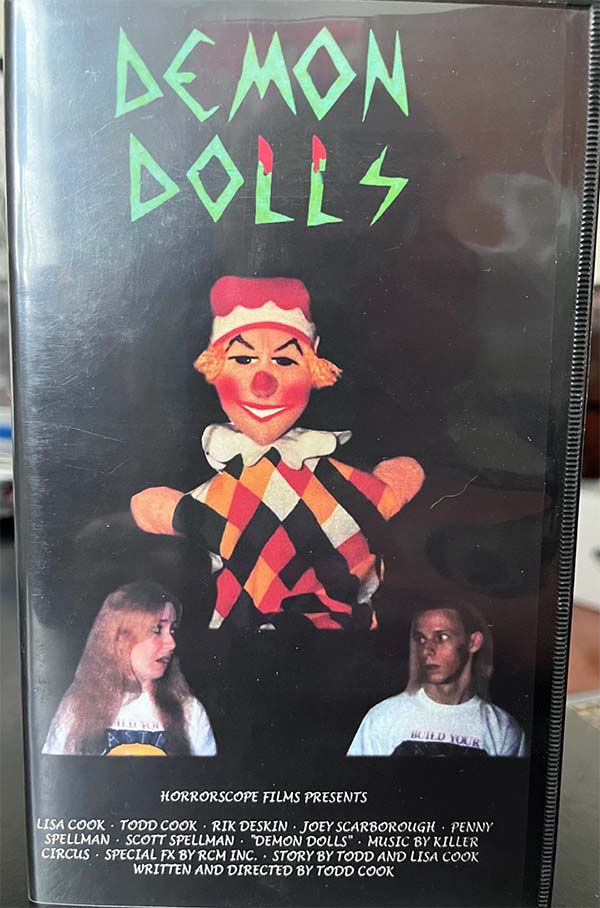

Demon Dolls — The masterpiece of Texan filmmaker Todd Jason Cook’s incredible eight film run between 1992-1995. Following his debut slasher Evil Night, Demon Dolls was Cook’s conscious attempt at scaling back his approach to produce something more surreal and insular. He succeeded wildly, crafting a film with a cast of six, shot almost entirely in his own home and centering the everyday possessions of his life as props and special effects. Later efforts from Cook’s Horrorscope Films doubled down on the nightmarish domestic insularity pioneered here, and Cook was one of many independent auteurs who defined their own success by self-distributing his works throughout the decade. Several of the films to follow, including 1997’s Frightmares and 1998’s Night of the Clown feature only Cook and then-wife Lisa as the sole cast and crew members. These aren’t recommended for newcomers, and instead Demon Dolls is the perfect example of subjective filmmaking and SOV horror’s many unintentional brushes with the avant-garde.

ZINES

Draculina — I realize in hindsight that I undersold the massive role Hugh Gallagher’s Draculina played in the rise of SOV horror as an independent cinematic movement. In fact, the magazine proved to be a crucial and much-cited reference for several chapters. It was simply one of the defining voices of the entire movement, and even a look at its letters or classified ads sections provides fascinating context into the homegrown nature of amateur video horror during the 1990s. Dating back to the late-1970s in various forms, Gallagher’s zine grew from a sparse black-and-white publication to a glossy full-color magazine proper by the mid-1990s. Through his video selling operations, Gallagher spread the word about various important and obscure SOV titles, like the films of US-expat Richard Baylor and the Italian oddity Arpie. Perhaps better remembered for its softcore nudity and centerfold Scream Queen spreads now, Draculina should be recognized for its essential role in disseminating the works of upcoming horror filmmakers and helping to canonize genre mainstays like Todd Sheets.

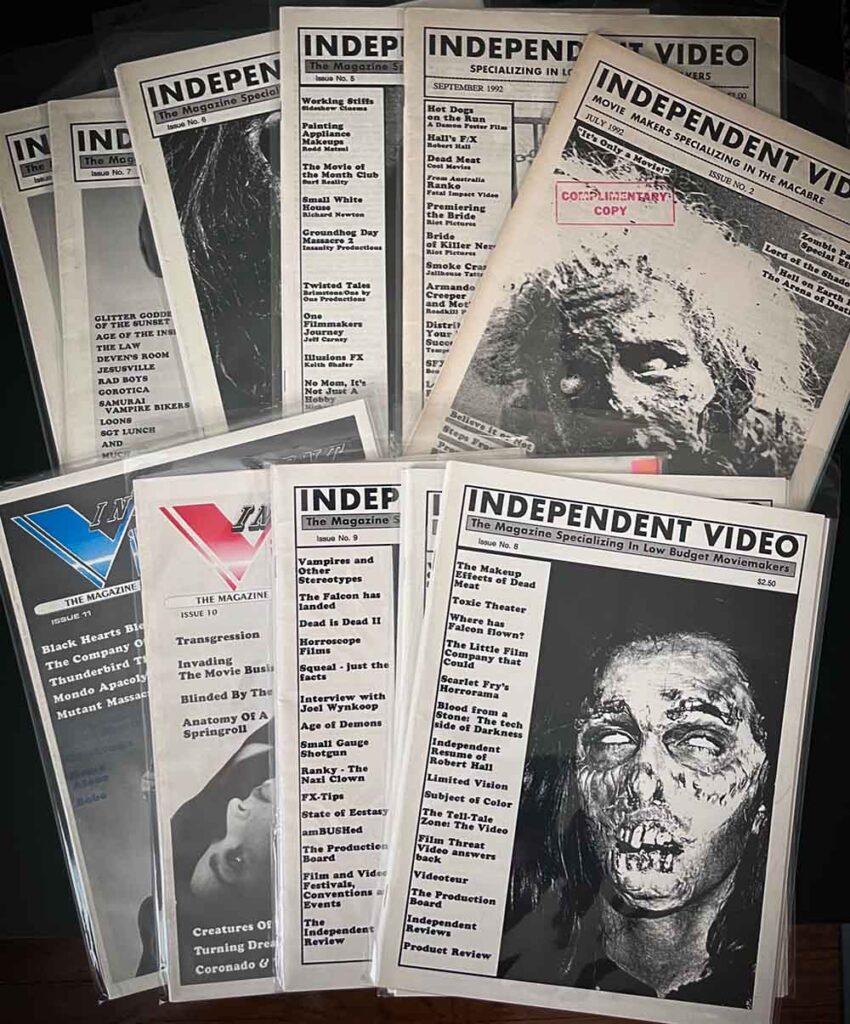

Independent Video Magazine — By far the most obscure yet exciting publication informing my research, James Stanger’s New York-based magazine ran for 11 issues between 1991-1995. The publication offered the most off-the-radar independent and amateur filmmakers a platform to promote and discuss their works at various stages of completion through self-penned articles and promotional materials. Independent Video remains a fascinating time capsule of the middle period of SOV horror, when directors were forced underground and instigated a grass roots filmmaking movement on their own terms. The evolution of the 1990s wave of amateur horror is represented through pieces by regarded filmmakers like Kevin J. Lindenmuth, Todd Jason Cook, and Carl Sukenick, as well as profiles of lesser-known curiosities like Kevin Brian (Deven’s Room, In the Company of Curtis), Mike Johnson (Tortured Soul, Deadbangers), and James Adam Tucker (Steps from Hell, Lunatic). Alongside these recognized works are countless others lost to time, left to entice with only print and photo materials to prove they ever existed at all.

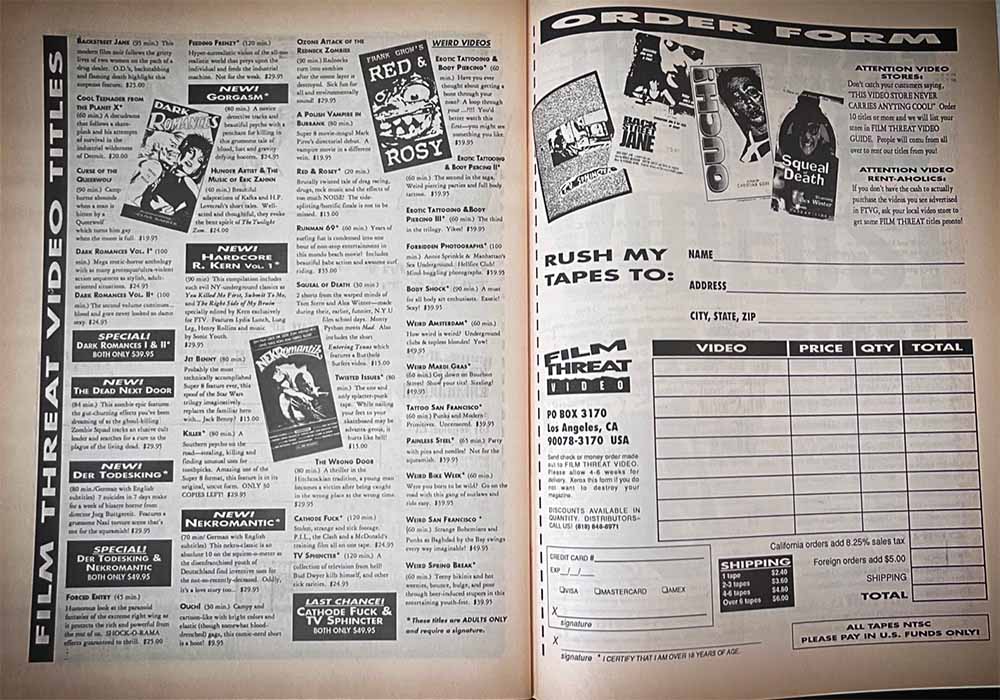

Film Threat Video Guide — One of the only publications cited in Aesthetic Deviations that should require no introduction. Chris Gore’s spiky, sarcastic zine-turned-magazine was the defining publication for an entire generation of independent filmmakers. While the Film Threat proper of the 1990s bore little resemblance to the maverick periodical of the preceding decade, Gore and editor David E. Williams retained the original zine’s edge with Film Threat Video Guide. Split between feature interviews and articles covering various essential underground figures (including Cinema of Transgression alumni, Mark Pauline of Survival Research Laboratories, and Jörg Buttgereit) and an extensive reviews section, FTVG was an essential guide to alternative cinematic culture in a pre-internet era. The reviews section is especially enlightening viewed in hindsight, as FTVG’s visibility ensured that they received seemingly every independently-produced work shot on video or film throughout the first half of the 1990s. Well-known titles like J.R. Bookwalter’s Ozone, Charles Pinion’s Twisted Issues and others rubbed elbows with underground luminaries like Michael Johnson’s Tortured Soul films and Independent Video editor James Stanger’s own mystery SOV I’m Not Crazy. Better still are the dozens of unseen and unknown titles that languished in obscurity following their brief exposure here. While Gore and Williams’ team of writers were no great fans of SOV horror, their scathing reviews inadvertently offer some of the only historical documentation of countless now-lost or forgotten works.

THEORISTS

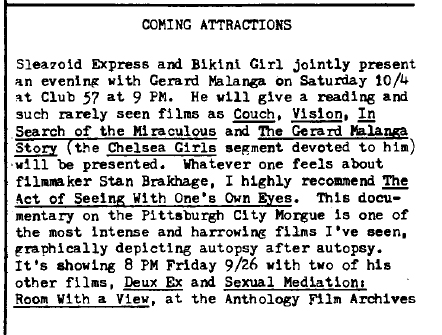

Stan Brakhage — Enormously influential avant-garde filmmaker who redefined the American experimental film scene several times over the course of his decades-long career. Despite his stature within academia and regular teaching assignments at the University of Colorado, Brakhage eternally considered himself an amateur artist, citing his approach to moments of everyday emotional significance and personal landmarks as the decisive characteristic of his work. Most known by underground audiences for his autopsy documentary film, The Act of Seeing with One’s Own Eyes (which was recommended in an early issue of Bill Landis’ Sleazoid Express), Brakhage’s films bear a number of shared thematic and technical contents with later SOV filmmakers. A personal favorite, and Brakhage’s breakthrough lyrical film, is Anticipation of the Night, which rewrote the rule of subjective film experience within the American avant-garde.

André Bazin — French film critic and theorist, widely recognized for his own writings on the medium of film, as well as his contributing role to the founding of Cahiers du cinema. Bazin’s chief concern was on the realist tendency in filmmaking, praising the value of works that replicate the nuances and intricacies of everyday life. For Bazin, this meant technical advances related to perception and presentation, such as the deep focus cinematography of Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, as well as the burgeoning Italian neorealist movement. Bazin’s theories on cinematic realism, however, also prove surprisingly compatible with the scaled-down approaches of numerous SOV horror features. Beyond the mere capture of everyday reality onscreen, SOV horror’s general dispensation with standard editing techniques recalls Bazin’s dismissal of such things as excessive manipulation and a distortion of the image offered of the world.

Jeffrey Sconce — Professor and writer responsible for the modern academic approach to cult/trash/exploitation cinema. His 1996 essay “Trashing the Academy” coined the concept of paracinema, a sensibility of cinematic refuse that allows for the serious analysis of works long deemed undesirable or unworthy of study. Using fanzines as a key example, Sconce investigates how an alternative culture of film scholarship exists which lionizes the obscure and unprofessional, which promotes an alternative canon directly in response to the more accepted mores of film studies and history proper. Key to the paracinematic approach is the ironic and oppositional reading style that it promotes, something I attempted to break with in my own writing. Nonetheless, Sconce’s work through the present day, as well as a number of responses to his initial essay have proven key resources for my work and continue to offer new avenues for exploring so-called badfilms.

-

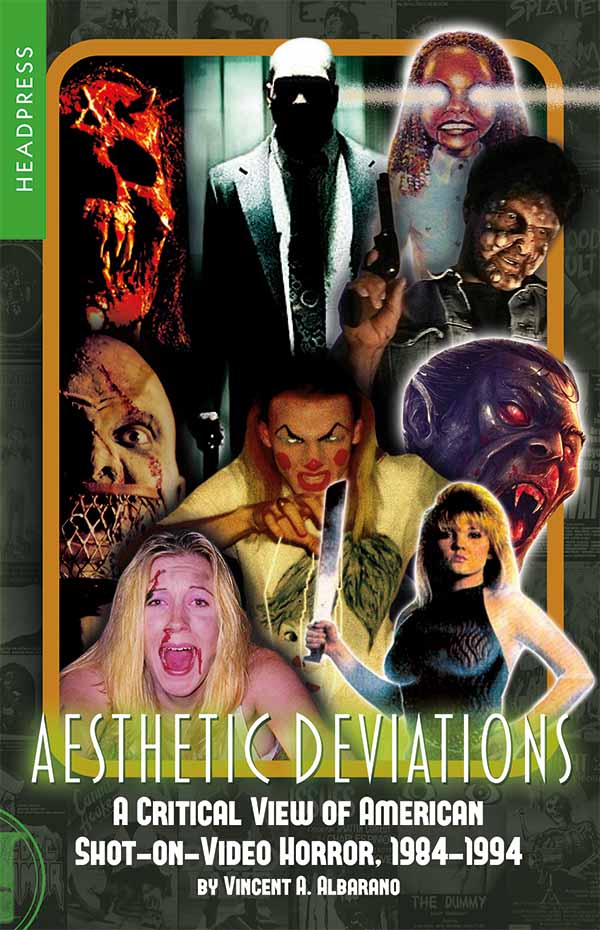

Aesthetic DeviationsThe first serious critical evaluation of American shot-on-video horror cinema. By Vincent A. Albarano.£9.99 - £22.99

Aesthetic DeviationsThe first serious critical evaluation of American shot-on-video horror cinema. By Vincent A. Albarano.£9.99 - £22.99

- Other

- Aesthetic Deviations, André Bazin, Bill Landis, Black Devil Doll from Hell, Demon Dolls, Draculina, fanzines, Film Threat Video Guide, George Romero, Hereditary, Independent Video Magazine, Insidious, Jeffrey Sconce, John Carpenter, Red Spirit Lake, Sleazoid Express, Splatter Farm, Stan Brakhage, Todd Sheets, Video Violence, Vincent Albarano, W.A.V.E., Who Cares Anyway

Vincent A. Albarano

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress