Eat Me! Notes towards a pezology

LAST WEEK, CALIFORNIA became the first US State to place a ban on four food additives that the Food and Drug Administration linked to a variety of potential ailments, including cardiovascular risk, anxiety and cancer.[1]

Among the 3,000 food products containing the cited additives (already banned in many countries) is Pez® candy.

The ban becomes law on January 1, 2027, by which time the additives need to be removed or replaced. In view of the ultimatum, we present this archive discourse on Pez, which originally appeared in Headpress 2.4 (April 2011).

What is Pez?

The Austrian candy executive Eduard Haas III invented Pez in 1927. The compressed sugar briquettes were peppermint flavoured, hence the name: PEZ®. Pez is short for the German word for peppermint: Pfefferminze.

The candy was originally marketed as a peppermint pastel for adults wanting to quit smoking. One dependency was to be exchanged with another, the harmful obsession replaced by an innocent one in that pastels took the place of cigarettes. Moreover, the dispenser was designed like a lighter and the pastels were pushed out and eaten in a ritual that was a substitution for lighting the cigarette, the movements being identical. Cute. The first dispensers (“regulars” to collectors) didn’t have character heads, though. They were added later when Pez was introduced in the USA in 1952. Here, the concept was changed in response to market research.

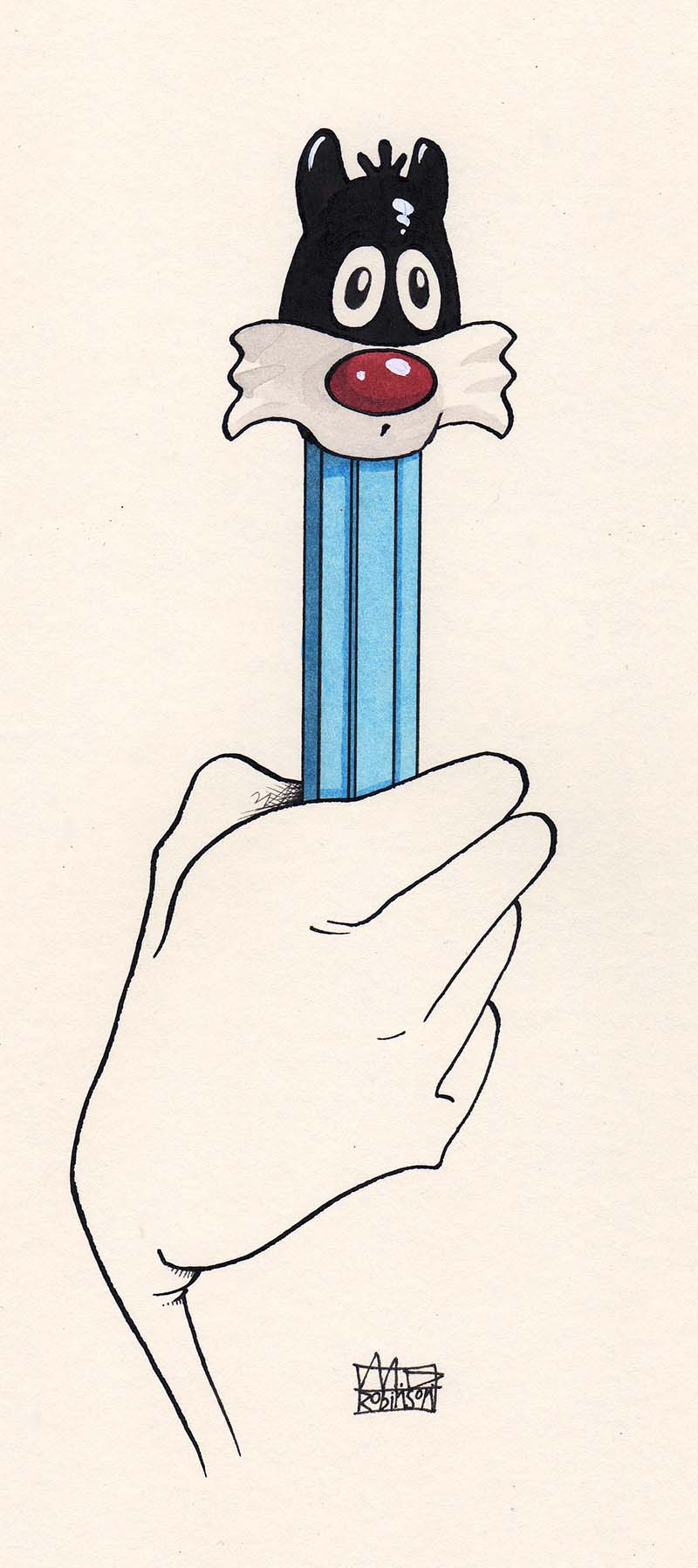

The booming postwar economy opened a new market among children and adolescents, presented as a group, with needs and desires, and corresponding products to satisfy them. Pez had once been a way out of dependency; now it was designed to seduce people into consumption on a large scale, with children as the primary target. The peppermint was replaced by fruit flavoured sugar, and the dispensers were adorned with character heads from the world of fairytales and cartoons, Disney being the greatest scoop. Mickey Mouse’s head was the first to adorn the top of the totem pole. Ooooh, aaaah! Pez turned into seducer.

True enough, there is something ambiguous, something fishy about Pez. It is difficult to tell what it is you are buying.

What is selling what?

The sugar briquettes come in four flavours: grape, lemon, orange and strawberry (originally cherry flavour). The ingredients are sugar, corn syrup, adipic acid, hydrogenated palm kernel & palm oils, soybean oil mono & diglycerides, natural & artificial flavours, artificial colours (FD&C Red 3, Yellow 5, Yellow 6, Blue 2[2]). It is fair to say that the candy doesn’t hold a great attraction. It is there for something else: the mechanical dispenser. That wouldn’t be the most exciting thing either, if it weren’t for the character heads. They turn the dispenser into a doll, being at the same time a toy, shooting briquettes out of the head. This, again, influences the candy, the very special, exclusive kind of sugar briquettes coming out of a mechanical doll. Pez — “a treat to eat in a toy that’s neat”.

The important thing, then, is not the contents (the candy), but the container and the decoration that counts, transforming the immediate use value, adding some higher, intangible quality to the product. This is generally true for most commodities on the market, where products are charged with secondary values and associations, which are often completely foreign to the products themselves. They express all kinds of needs, wishes and dreams in phantasmagorical pictures that suck out the emotions and fantasies of the public. The invested emotions take on a life of their own in a spellbound world of commodities, only to be released and regained through the act of buying the product in a cycle of wish fulfilment that never happens.

What is the promise of Pez?

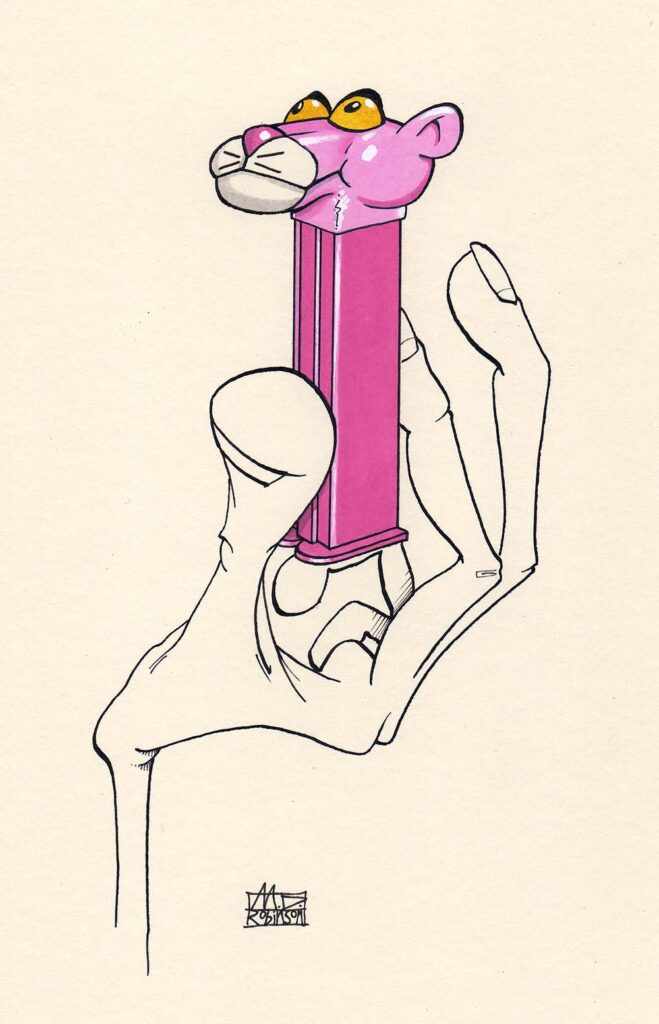

The dispensers with heads come straight out of fairytales and cartoons; Disney. A universe, that is, where the reality principle is suspended; where anything can happen, and all and everything can be turned into everything else in an endless metamorphosis. No stable subjects and objects: the protagonists are readily transformed into objects, such as bowling balls, while the inanimate world comes alive with limbs and senses and other subjective properties. Just like Pez.

This type of perception is akin to psychotic states, and belongs to an early age in life, when the objective apprehension of one’s own body and the environment has yet to be established. The young child experiences everything in a symbiotic continuum with itself, and doesn’t distinguish between consciousness, body and environment. On the one hand, then, Pez represents an infantile, anthropomorphic world, activating strong emotions: the candy coming out of the dispenser associating it with (breast-)feeding, even making it possible to incorporate Mickey Mouse, Papa Smurf, and all the other figures on an oral, cannibalistic basis.

On the other hand, Pez is a purely subjective reality incarnated into a physical object that can be manipulated by the child. In that respect, it is a typical transitional object, the type of objects that fill out the ‘hole’ between the individual and the surroundings, when the symbiotic continuum is broken by the experience of frustration and social demands.

Transitional objects

Transitional objects can be anything from a pillow to regular toys and dolls, which have a fantasy connection with the child or the nursing person, but at the same time have a certain degree of objectivity. They constitute a mediating space between internal/subjective reality and external/objective reality. Having been bombarded with aversive or pleasant stimuli without the possibility to control the situation and react in any other way than by passive motor responses (crying, blushing, etc.), or hallucinatory, the child is now projecting the sensual experiences — the impulses, and the emotions — investing them in an object, and thereby getting the ability to express them in a symbolic way.

Identifying with the role of the nursing person, the child can establish some distance and exercise an active, subjective control over its own body as an object, represented by the cherished doll, the teddy bear, and somewhere down the line, Pez. Pez holds a special attraction in this transition, where the child must give up the happy fusion with its sensuality and externalize and objectify itself. The dispenser magically transforms the invested emotions into fruit flavoured briquettes, recycling the energy back to the body, with a sweet, pleasant release of tension on the tongue as a secondary gain from the effort.

Growing up, the rather passive pleasures and toys from early childhood are abandoned for other activities in accord with the biological and psychological development. This might have posed a problem for Pez Candy, Inc., who would want to prolong the demand for dispensers and candy. In the 1970s the company marketed an innovation: the Pez gun. This beauty from the heyday of plastic gadgets was able to shoot briquettes into the mouth, and, even better, shoot them at people and things around you. In other words, it was made to match the active, aggressive and object-oriented behaviour of older children, thus keeping their interest in Pez. The gun is long out of production, but other merchandising has popped up over the years, like the Pez truck, the Pez watch, Pez jewellery, Pez Christmas ornaments, and the 500-piece Pez-azzle jigsaw puzzle.

Character heads

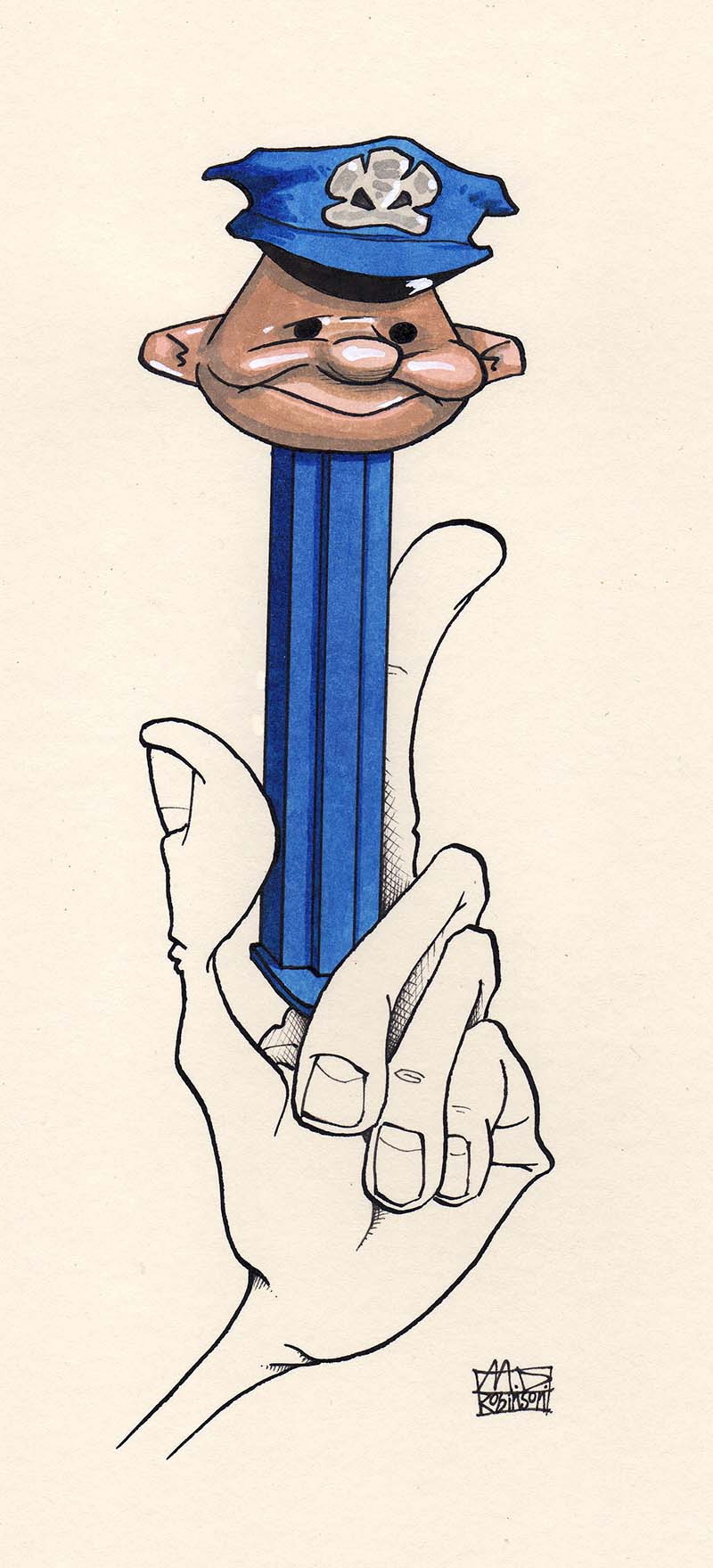

The same concern determines the design of the character heads. All in all, 275 different models have been produced since 1952, forty-eight being in circulation as of writing. (Indeed, forty-eight seems to be the number in circulation at any given time.) They are constantly changing to keep up with current trends, promoting figures such as Muppets, Ninja Turtles, Garfield, the Flintstones and Monsters vs Aliens. It doesn’t stop there: Pez superheroes, Pez Policeman, Fireman, Nurse, Bride, Engineer, Astronaut, Pez Baseball Glove, Pez for the Olympics, the Bi-Centennial, Christmas, Easter, Valentine’s Day — even Death has been pezified into a skeleton with a scythe. Ideally, there would be a dispenser for every popular character, every social role and occasion, everything on earth. A Pez mirage.

Until recently, the company avoided dispensers of real people, focussing instead on the imaginary and the distant, which is essential to the attraction of the commodity as something other and out of reach in a world of fantasy and universal representation. One of the few detours into real life is Pez Elvis, who arguably fits the bill of a stereotype anyway, of the imaginary and the distant.

The effort to renew the appeal of the same product and stimulate identification by changing and widening the repertoire of character heads has fostered some pretty weird dispensers, like Psychedelic Eye Pez and Psychedelic Flower Pez. The inroads to an alternative culture such as the hippy movement were repeated a few years ago, with Pez Spike representing the aggressive, depressive and destructive replay of another youth revolt: Punk. But what has a cute toy like Spike got to do with raving, suicidal punks? Nothing. It is a negation of the negation; pulling the thorn of the protest, stereotyping it according to mainstream aesthetics and behavioural norms; an act of repressive tolerance. Moreover, it is a perfect example of capitalist society incorporating any given subversion and revolt, commercializing it, and selling it as a commodity affirming the selfsame system that is put into question.

Would a punk buy Spike? No, and kids probably won’t pick Lions Club Pez, either; the parents would (well, they certainly need to now, as it’s classified ‘extremely rare’). There is another reason why they are so important to the company. Having successfully survived one generation, Pez found itself with a market of children that has since become parents, predisposed to give the dispensers to their own children. The toys of childhood are also the objects of nostalgia, where the rich associations and emotions are savoured in a thing like Pez. The circle is closed — a perfect system, as the company blatantly states in its promotion brochure:

“Over one billion Pez Candies are consumed annually in the U.S.A. With great tasting flavours and collectable dispensers, Pez is more than just a candy… It’s a ‘system’ that is both enjoyable to eat and fun to play with. Pez Candy is a favourite of kids in America and around the world, while giving millions of adults nostalgic memories of their youth.” [3]

What is the market for Pez?

The transformation from neglected toy to precious memorabilia is closely related to Pez becoming a collectable. The urge to collect is already stimulated by the serial production of Pez, bringing out dispensers in groups with related character heads: Disney, Warner Bros, themes like Kooky Zoo, Crazy Fruits, or bonding like Pez Pals, Fuzzy Friends, Mr. Ugly and Bubblemen. What would Tom be without Jerry, Kermit the Frog without Miss Piggy? A family like the Flintstones would be close to a tragedy if Pebbles was missing. The serialization spurs desire, the state of tension only overcome by buying the whole set and completing the group. The next step, the ultimate closure: Getting them all.

Collecting Pez can turn into an obsession. There is no real ‘end’ to the hunt by possession because the quest for missing dispensers isn’t motivated by the qualities of the objects. They don’t make any sense in and by themselves, only as signifiers pointing at some opaque, repressed meanings and emotions (childhood, mom, dad, sex, whatever). Those afflicted are known as Pezheads, idealizing and fetishizing Pez, cultivating a highly specialized field of knowledge (the styles, colour variations, limited series, rarities.). The characters in the Circus Elephant series, for example, are frequently found with an orange head, green tongue and blue, flat-topped, round hat. Less common is the version with a Chico Marx-type hat, also found in several other colours, while the rarest of the elephants is the one with a yellow face, wearing some sort of reddish-brown wig (a case of using up spare parts by the Pez company?). The dispensers are thus scrutinized in several books, such as Pez Collectibles by Richard Geary, The Collector’s Price Guide to Plastic Pez Dispensers by Mike Edelman, A Pictorial Guide to Plastic Candy Dispensers, Featuring Pez by David Welch, and the Bible for collectors, again by Welch, Collecting Pez.

There used to be a newsletter and a zine, The Optimistic Pezzimist, published by Mike Robertson in Texas. It is now defunct, as are Fliptop Pezervation Society and Pezzer International Newsletter. But Pez Collectors News, which first appeared in 1995 and is still running, is ‘thirty-six pages of stories, articles, dealer ads and hobby related information’. There are many online resources for fans and collectors, Pezhead Monthly being just one of them.

Dive into yesterday

To some degree, Pez has gone through the process whereby today’s transient, mass-produced gadget becomes tomorrow’s worthless, undifferentiated junk, and then turns into a prized durable from yesterday. Pez is being exhibited, sold by antique dealers, and auctioned at Christie’s. The scarce, discontinued, older dispensers (said to be “retired” among collectors) are selling for hundreds of dollars. Not too long ago the record price paid was $1,150 for nineteen Disney characters, the poor man’s substitute for a set of antique statuettes. More recently, a 1950s Pez space gun was sold on eBay for over $11,211 (and is regarded by some as a fake).

The first annual gathering of collectors and Pezheads took place on June 15, 1991, at the Pez Dispens-O-Rama in Mentor, Ohio. They are now held annually all over the world.

Today, Pez Candy, Inc., is in Orange, Connecticut, USA. Here the candy is produced, and the dispensers are packaged. The dispensers themselves are imported. They are manufactured in Austria, and more significantly, in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovenia, and China, exploiting the low cost of production, minimum wages, and selling the dispensers in affluent western countries with a sound profit. In that respect, Pez is capitalism in a nutshell. Or, rather, in a dispenser. It is an allegory for alienation, because there is nothing in it that you didn’t put there yourself in the first place by filling the dispenser. Just like the appropriation of work by capital, where the products are taken from the producers and reappear as a foreign power on the market in the form of commodities to be bought by the wageworkers as consumers. Why is it that the candy seems magically transformed and strikes you with surprise every time it pops out of Uncle Sam’s head?

So then, pezology is a science in the making. It will take a while before the world is totally transformed into Pez, but Pez itself has established a secure and ever-growing presence in the world. Praised by rock stars, featured in high profile magazines guest starring in TV shows and movies, exhibited in museums, the commodity has become an icon, and the dispenser indispensable.

Notes

[1] ‘No, California hasn’t banned Skittles. Here’s what new law says,’ BBC News, October 12, 2023. <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-67058928> (accessed October 16, 2023).

[2] 2023 NOTE: Red Dye No 3 is the offending additive under the new California ruling. The other three additives, although not appearing in Pez, are brominated vegetable oil, potassium bromate, and propylparaben. ‘4 Food Additives Banned,’ The Brief, October 10, 2023 https://laist.com/brief/news/california-becomes-the-first-state-to-ban-4-food-additives-linked-to-disease (accessed October 16, 2023).

[3] Since writing, this press release has been updated. The official number of Pez candies consumed in the USA alone is now quoted as “billions” < www.pez.at/ > (accessed October 16, 2023).

Knud Romer Jørgensen

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress