Appliqué Tapestries in London Town: Goodbye, John Sinclair

Gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta / gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta, gotta / Gotta, gotta set him free

‘John Sinclair’ by John Lennon, Northern Songs Ltd.

IN 2007 I SHARED OFFICE SPACE in Dalston, northeast London. It is tarted-up now, but at that time, as Alan, a pragmatic delivery driver explained to me, Dalston felt not like London at all but a different country. Indeed, it was a curious place and this a curious time, each day a market day, a fruit and veg day, with a bewildering array of unlock your phone services at every turn. Among the constant procession of people was the occasional bobby on the beat. Headpress, a unit located off Kingsland High Street in a building that once manufactured artist colour materials, was publishing books with alarming irregularity in an age heralded as the last for print before digital books took over.

I was living some miles north of here. What struck me on my daily commute was the volume of Argos catalogues. The retail chain had a significant presence and its free catalogue, each a small rain forest, began the morning stacked high on a pallet outside the store near to the 67 bus stop and from here propagated the public transport routes out of Haringey. It was the reading list of the dispossessed, a glossy compendium of jewelry, household cleaning agents and every product in between. It could easily have deflated the publisher of quality books, but the irony was not lost. Here, if nothing more, was evidence that the death of books had been greatly exaggerated.

I wondered what George Orwell might have made of it, Argos catalogues and cigarettes. In the early 1990s, when Headpress started, “transgression” had been the buzzword for a burgeoning counterculture, as had “peace” and “love” in the 1960s, for an earlier, more optimistic counterculture. These anachronisms collide with the arrival of John Sinclair.

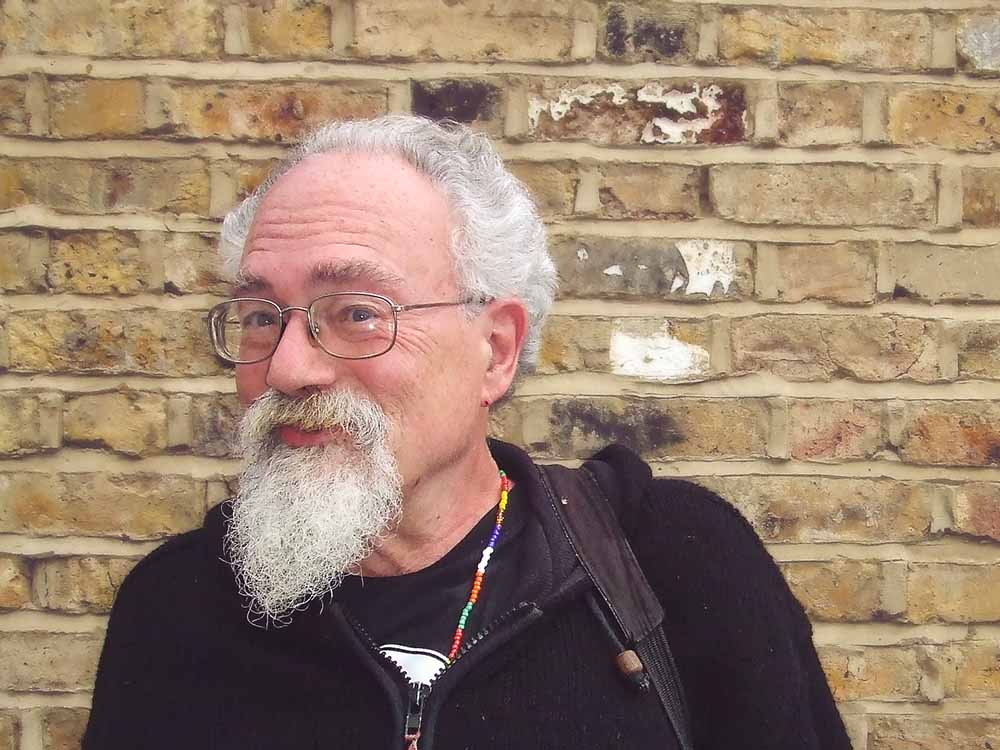

The legendary John Sinclair.

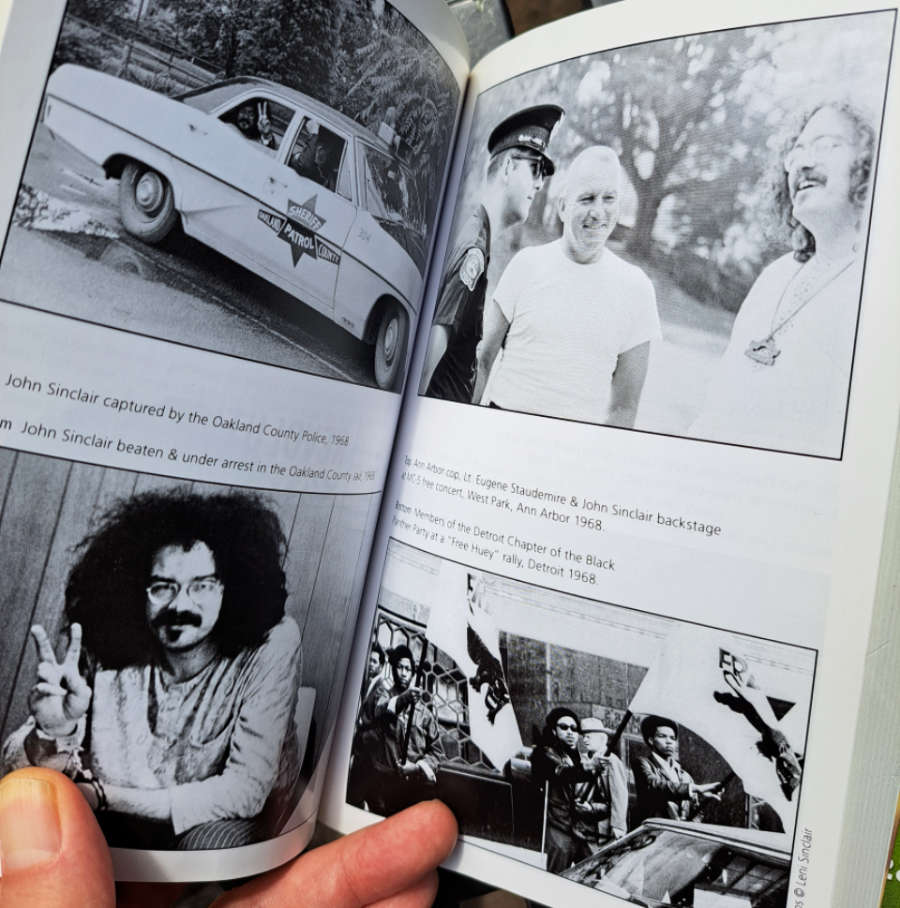

Ten For Two

Born in 1941 in Flint, Michigan, a city associated with high crime and poverty, moving to Detroit with its endless streets “once filthier than you would care to imagine”[i], becoming an activist, poet, manager of rock band MC5, and co-founder of the White Panther Party (anti-racist cultural revolutionaries aligning themselves with the Black Panthers), John Sinclair shot to international fame when he was arrested for selling two joints to an undercover police officer in 1967. I like to think she looked like Angie Dickinson. The sentence was an excessive ten years, and many rallied in John’s support, including Beatle John Lennon, who wrote the song ‘John Sinclair’ and elevated the profile of the Free John Sinclair campaign.

I first met John when he visited London in July 2007 in a promotional drive for a new book. His London publicist happened to be my landlady, Jane, struggling to drum up media interest in a sixties American revolutionary. She asked for help and, with Lennon’s ode playing in my head, I happily obliged with an interview for Headpress.

John was larger than life. He wore a big yellow-white beard and when we met occupied the living room of a house belonging to an associate of mine, filling the space as only a man immortalised in a song by a Beatle can. John didn’t much like to walk. He raised himself from the settee, shook hands, and sat cautiously back down, smiling in a charmed and charming way. Somewhere in that house was a spliff; it was considered good form to offer John a joint, an unspoken etiquette in most places he visited, although he was rarely without and even put his name to a brand of potent ganja, described on the John Sinclair Seeds website as “very smelly and strong as an Ox”. Preparing for the interview, I discovered a more subversive character than simply two joints. Certainly he was unfairly imprisoned for marijuana, a sentence reduced to twenty-nine months following a benefit concert in December 1971 that featured, among others, John and Yoko, Stevie Wonder, Phil Ochs, Archie Shepp, Abby Hoffman, Allen Ginsberg, and Bob Seger. Lennon’s involvement effectively quashed the sentence. Determined John years later: “Lennon had put the key in the lock, and the legislators were turning it.”[ii] But John was nothing less than an enemy of the state and, in 1972, was charged with conspiracy to destroy government property following his alleged involvement in the bombing of a CIA office. The case went to the United States Supreme Court.

Things like bombs were a way of life in sixties and seventies America. This I discovered in Days of Rage, a book by Bryan Burrough about revolutionary violence of this era.[iii] Urban guerrillas were so prevalent that for many people in the major cities, incendiary devices were not so much a threat as a nuisance in the day to day grind. Then Watergate happened and suddenly President Nixon had bigger fish to fry. Operation COINTELPRO, which had led to the conspiracy charge against John and his compatriots, was also part of the wiretapping scandal at the heart of Watergate and consequently the charge against John disappeared. He told me in our interview that he much preferred poetry and dope these days, making life a lot less dangerous. He begrudgingly spoke of his political past, worried it might remind the wrong people that once he had been a ‘serious’ man. Someone on a government slow day, he said, might revisit a dusty file to discover the case against John Sinclair had never officially been closed.

Primal Scream

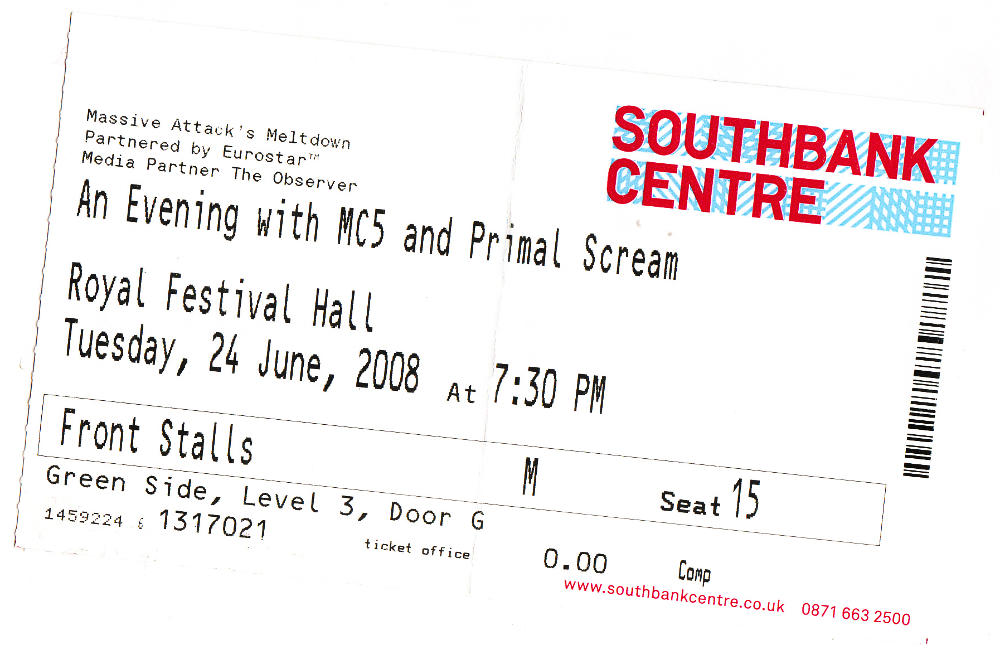

John’s early tenure as manager of the rock band MC5 is well documented and helps cement for him another aspect of the freewheeling sixties counterculture, that of champion of a hard rocking, pioneering proto punk spirit. The sleeve notes for the original release of the band’s 1968 debut album, Kick Out the Jams, is a White Panther manifesto in which John, credited as Minister of Information, implores the record’s young listeners to riot, to take to the streets “yelling and screaming and tearing down everything that would keep people slaves”. Forty years later, for the final night of the annual Meltdown festival in London, June 2008, John was invited onto the Royal Festival Hall stage by Primal Scream and what remained of the MC5 to deliver an impassioned tribute to Rob Tyner, the Detroit band’s late singer. Later in the evening, the two bands performed a psychedelic jam together. Call it acid experience but the MC5 component in the sonic onslaught was merciless, effortless, and debilitated the younger brothers, the association doing nothing to offset John as the noblesse of high energy rock and roll truth. Nonetheless, John’s bag at this point was well and truly blues and jazz. Rock once interested him but not now — although he was always polite whenever a band kicked out the jams on his behalf. He was happy with the CD that accompanied one of the books he published under Headpress. It’s All Good: A John Sinclair Reader is a collection of his poems and essays, accompanied by iconic photographs taken by John’s former wife, the wonderful Leni Sinclair. The CD contained thirteen of his poems with blues and jazz backing tracks. These were mastered by excellent improvisational bassist Jair-Rohm Parker Wells, whose musical signature is markedly different to Motor City’s rock and roll rebellion.

On Planes of There

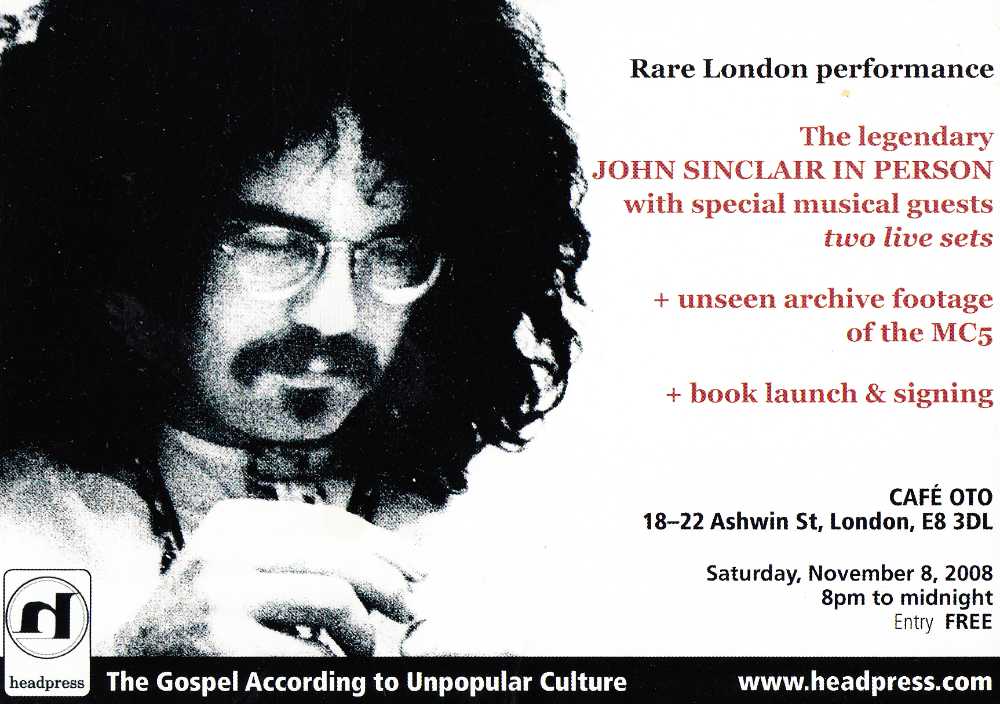

Among the tracks was Ain’t Nobody’s Bizness, a poem that demands a right to bad habits, backed on the CD by MC5’s Wayne Kramer and the Blues Scholars. It comes close to a mission statement for John, a personal work that reminds me when I read it now of a rampaging Philip Larkin. It was performed by John on the evening of November 8, 2008, at the Cafe OTO, a leftfield creative space conveniently located in the old Colourworks in Dalston. My office was at the top of this building, a triangular loft with a fist-sized skylight. Access was via a thin staircase behind a door and thus hidden from other staircases. To reach the office one had to keep climbing. Film posters decorated the walls and in my desk drawer a bottle of Borsci Elisir S.Marzano, a liquor, the remaining spoils of my pursuit of tarantism across Southern Italy. The heat in this small space and the accumulative chatter from the floors below—one floor occupied by a call centre, a hot rumble of incessant dialogues—induced even greater heights of displacement. This, thought I, was a fitting place for Headpress. So — down the thin staircase, down three more flights and out through the gated entrance, around the building to the other side, to Cafe OTO and John Sinclair, whose backing band that evening included a host of musician-friends.

The Cafe OTO event marked the release of Headpress 28, the Headpress flagship journal in its final incarnation as a trade paperback, commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the White Panther movement, spearheaded by John in the 1960s. It carried his name as editor, as did another Headpress publication, Sun Ra: Interviews and Essays, a book devoted to the enigmatic free jazz musician and composer, professed to have come to Earth from Saturn. John interviewed him in 1966, talking God, philosophy, the planet, and “other Planes of There”.[iv] There was a host of contributors to Sun Ra and archive concert photographs by Gregory Ego. One of my own contributions (co-authored with Caleb Selah) was an interview with Haf-Fa Rool, an older black gentleman who once was Sun Ra’s mystic and credited as much on an early album. Haf-Fa liked to talk, John not so much. Memory is a little fuzzy, but both were present when the Sun Ra Arkestra under the direction of Marshall Allen performed a five-night residency at the Cafe OTO in August 2013 — here, then, a poet, a mystic and a big band leader, hanging around like the preface to a Grimm morality tale that could be epic. Haf-Fa is another interstitial aspect to this story, but one destined for another day.

Covers for John Sinclair edited books published by Headpress: Headpress 28, Sun Ra: Interviews & Essays, It’s All Good: A John Sinclair Reader.

A Tiny Impractical Backyard

My Dalston office relocated to Wood Green in the borough of Haringey, some miles down the road, specifically a room in a large terrace house on a street overlooking the tube station. This was another curious place, a house packed with delicate wooden furniture and the spirit of an absent landlord. Of course, the battered filing cabinet that came with me was out of sorts among the appliqué tapestries. Alan, who had helped to drag the thing from Dalston, did so while negotiating each obstacle with an alarming Jimmy Savile impression.

From the outside it was a normal looking back-to-back house, with a tiny impractical backyard, nothing to suggest a publishing house within. Day by day, the house and its occupants adapted to a communal singularity, as if travelling in fits and starts back to funky town, or at the very least the 1960s, for John, too, had relocated. Based in Amsterdam, home to John’s radio station, Radio Free Amsterdam, but moving to London at around the time of our interview, he too found himself at the house. (It hadn’t been difficult to maintain a weekly radio programme from afar.) In London John acquired a manager, someone with a fondness for the legend who also happened to be resident in the normal house. Remember, these times were loose and the notion that a poet — self-styled the hardest working one in the business — might become again the spokesperson for a generation seemed entirely plausible. More than anything, John needed paid gigs, because, despite the roof over his head, he was effectively transient. With a handshake John accepted his new manager but I suspect didn’t really care one way or another. This was the way the world rolled for John. The glint in his eye told me as much.

From the Underground of the Upper Midwest

While the media was largely indignant, there were many who gravitated to John. As well as a manager, he had a benefactor in London and consequently his modest room in the normal house in Wood Green was rent free. It was a room located on the upper floor, opposite the room I called my office. His contained a bed, table and chair, and decor in keeping with the rest of the house except for the addition of a handful of pictures, a half dozen or so, pinned to the walls. These were people and festivals of which John was respectful and proud. One photograph showed John himself as a young man, a mass of bespectacled hair rolling a joint, taken by ex-wife Leni back in the sixties. “How does it make you feel?” I asked. The photograph is iconic, but its presence on the wall was at a distance to the others. John was dismissive. “What is this, Geraldo Rivera?” he replied.

John travelled light. I noticed that the books regularly gifted to him, inscribed with salutations to the effect of “from one revolutionary to another,” never increased. He didn’t hold onto them, he gave several to me, having neither the room nor inclination to be carting stuff around (“we have a right to … walk around the streets with all our belongings in little bags,” as he says in Ain’t Nobody’s Bizness). One thing he did hold dear — dope — regularly manifested itself in the house, a thick cloud of marijuana smoke that escaped from beneath his door, compelling me to close mine.

John could be found each morning seated at the kitchen table reading a well-thumbed paperback, framed by the window that looked onto the small backyard with its population of sun-bleached plastic chairs and children’s toys belonging to no one. Here at the kitchen table he remained with his American detective novel until the house came alive and then he would disappear.

A former member of punk band Cock Sparrer popped by one day with a self-penned musical tribute burned to CD-r. It was a breezy composition, but its subject happened not to be in, so we listened in the kitchen, John’s manager and me, congratulating the composer, who listened with us, and diligently passed the CD-r to John on his return.

Old friends of John’s stopped by, finding a floor or spare bed to sleep on. Not all of them were musicians; I sometimes discovered a tie-dyed ghost from the underground of the Upper Midwest washing dishes in the spirit of communal camaraderie. These men had been around the block and passed through London with things to do but I never understood what. We exchanged cordial greetings and not much else, except for one day when a panicked scream split the silence of the house. It wasn’t a severe injury but something altogether humdrum, as I discovered on dashing down the hall to investigate: one of John’s guests had dropped a partial denture down the bathroom sink. I can’t remember the name but here was a gaunt man, holding the edges of the sink and staring into the plug-hole abyss. We will call him Randy. “Oh no! Oh man!” wailed Randy. The missing tooth was out of sight and therefore considered lost. I looked too, and then removed the U-bend to retrieve the fallen item. It was an easy fix, tooth and Randy were soon reunited, but this simple feat of plumbing brought so much joy that it may as well have been an act of high magic.

It gladdens me as well. Not so much the plumbing, a practicality to avoid, but Randy’s defiant lack of reality, the innocent belief that things out of sight cease to exist. The incident makes a fitting analogy: John and perhaps Randy and other interlopers in that house had brought down the Nixon administration in a peripheral, not so peripheral way. Key to Watergate was a special investigations unit that inadvertently toppled the President it sought to protect — this unit was called the White House Plumbers, or simply Plumbers.

A Dramatic Imperative

Another arresting aspect was the voice. John had a wonderful, gnarled voice that gave the most ordinary conversation a dramatic imperative.

“More coffee, John?”

“Thank you. I would love more coffee, Dave.”

Weed, specifically Amsterdam skunk, has an influence on the larynx. According to Mark Ritsema in his introduction to It’s All Good, it lowered John’s impressive speaking voice even more.[v]

John didn’t ever read aloud the entries in the north London telephone book from beginning to end, an idea mooted on more than one occasion, not entirely seriously but never dismissed outright either; less likely ideas gained traction in the London years. Here, the intention was to exploit that voice, John’s compelling noise, turning the telephone book’s cold list of names into hypnagogic performance art; imagine the spirits of William Burroughs and Samuel Beckett by way of a call centre. Likely it would have taken an age to produce, and likely the idea would invoke Dada, but the effect would have been nullifying and, fortunately, John never got to hear of it.

While the telephone book didn’t happen, the voiceover for The Bowl did, a pseudo-documentary by Smile Orange focused on a shopping and business district in a city in the north of England. John’s blind reading of the script, his accent diametrically opposed to that of the people of Bradford who populated the documentary, took place in the living room where I had interviewed him. The Smile Orange crew assembled their equipment and shot him against a green screen, later superimposing John into the film. It was scheduled to take only a few hours, but filming occupied much of the day, not because of any shortcoming on John’s part, the consummate professional, but because the crew cracked up laughing whenever the silly script called for him to refer to the Bradford strangers, credited with unlikely names, as being his good friends. Bored and impatient, he later called the filmmakers “very unprofessional”.

I watched the film again recently. A curious agitprop anomaly, typical of Smile Orange, it buries social comment beneath toilet humour, but with the added abstraction of a former White Panther as narrator. Don’t look for the film on IMDb, The Bowl is absent from John’s canon of work, which is entirely appropriate given the unmapped years from which it emerged.

English Fish and Chips

John was never stopped or cautioned by law enforcement during his London sabbatical (I’m not sure what else to call it). In a drive to combat drug abuse, police with sniffer dogs were common in and around the tube station, and yet John, who travelled everywhere with a fanny pack that contained only dope, always managed to avoid them. I suspect the stately eminence of a person like John diverted their attention to less significant targets. The fanny pack was with him as we made our way to the cafe on the corner, a place in Dalston selling fish and chips. Fish and chips was our design, fish and chips being John’s favourite (with canned tomato soup a close second). Along the way he asked where he might buy a copy of The New York Times. He didn’t mind that the international newspaper was days old by the time it came on sale in the UK, but in the age of the Argos catalogue I doubted any local store carried it. The nearest outlet, I surmised, was Liverpool Street train station. Rather than embark on a round trip of close on an hour through rush hour traffic, I reminded John that our mission was lunch, English fish and chips as he called it.

Dalston streets are crowded and the grim determination necessary to travel them can be exacting at the best of times. John was not entirely comfortable on his feet, less so when he simply became another obstacle in the busy diorama. At Dalston Junction the arrival of a train added to the melee with people zigzagging out from the turnstiles, off to market, off to lunch, oblivious to the cultural significance of a future passed, the living legend in love beads negotiating a path around them. At times like this — John Sinclair on a fish and chips day — a sense of cosmic unanimity presents itself. Strange cogs engage and it seems to me, as it did then, the world is a Harlan Ellison story, that everything real is supernormal. Nonetheless, I felt no obligation to travel to Liverpool Street Station to fetch a newspaper.

“John, that’s miles away,” I said.

The cafe on the corner was no less busy; two dozen tables rammed with diners with elbows and meals and bland white plates illuminated by garden peas and spots of ketchup. The place was warm and its window onto the street dripping with steam, but a kindly member of staff appeared, indicating the availability of seats at a table beneath the specials board and then rearranged the table’s occupants to secure them. We thanked her and sat down, John opposite me with his back to the specials board. He picked up a plastic laminated menu and relaxed. This was the sanctuary of English fish and chips and he had known exactly what he had wanted since leaving the Headpress office a half-hour ago.

“Fish and chips,” he said sagely, barely glancing at the menu.

The kindly staff member wobbled the notebook and ballpoint pen in her nicotine stained fingers. This was Wednesday, she said apologetically, pensioner day. “No fish and chips on pensioner day,” she advised, “only what’s on the specials board.” She pointed her pen at the specials board, on which was written in big chalk letters, ‘Cottage Pie.’ John refused to look.

“The special is cottage pie,” I informed him.

“Cottage pie?” he said incredulously. His expression betrayed the counter revolutionary in him. I tried to explain the concept of cottage pie while he reminded me he had wanted fish and chips all along. He remained unhappy but there was no alternative. Looking begrudgingly into my eyes, he finally acquiesced.

The order arrived in minutes. John’s cottage pie sat in front of him, beef mince beneath mashed potato swimming in a patina of gravy. He prodded the food with a fork.

“It’s nice,” I said, valiantly.

John may have taken a small mouthful, I can’t recall, but he returned the fork to the table with a growl. “This is not what I wanted. I wanted fish and chips.”

Sometime in New York City

The mystique of celebrity is undiminished by ordinariness. John was a veteran of the psychic wars, weird scenes in the sixties in which detachment from society becomes the norm. Arguably this was the easy way, often what John’s poems are all about. But, living hard and as laid back as John appeared to be, is akin to the shakes, collateral damage for one’s ideals and getting the just cause kicked out of you. Few of John’s peers had as many diametrical tangents and yet they seemed to manage the fallout less well. John was neither arrogant nor entitled and while the cottage pie episode came close to reducing the big man to tears, there was also the time he called to offer his condolences on my mother’s passing. It happened to be the day of another Headpress event, a launch party for Keep It Together!, a book about London’s communal bands of the 1960s and 1970s, which included live music by members of those bands. I didn’t attend. I was in Manchester for the funeral when John’s telephone call came, the last thing I wanted at the time in all honesty, a short sad soliloquy with the noise of Mick Farren and The Deviants banging away behind it.

I cannot say that John and I were pals. We didn’t hang out, but then I never got the impression he cared much to hang out, not even with the guys who visited he called friends. Sure, we shared company, at events and on a weekend in Amsterdam when visiting John in the city he called home and guesting on The John Sinclair Radio Show (ostensibly to talk Headpress but failing to get much beyond a recent experience with a cheap tourist map[vi]). To paraphrase the song in Eraserhead, he had his things and I got mine.

John was a man on a mission, absorbed in prose, music and weed, a counterculture extrapolated from the 1960s. He appreciated that I too was on a path. “Headpress,” he would say, pausing a moment at the door to my office. Sometimes he would say it more than once, a mantra, and turn away having said nothing more, back to his room or downstairs to the kitchen. There approximated fondness in his voice, the two syllables weighing on the air long after he was gone. While not pals, we extended to one another the courtesy of men of a shared space, occupants of a world that happened not to be in the same place or time. Only once did I talk to him about the song that shadowed his life. Having escaped a London gallery to which we were invited and relocating to a nearby pub (John didn’t drink; I did), I felt it prudent to explain what the John & Yoko Plastic Ono Band album, Sometime in New York City (1972), had meant to me as a teenager. It was the late 1970s, I told John. I lived in Manchester and wore a black t-shirt with iron-on silver-shiny letters that spelled out the words, ‘Plastic Ono Band.’ I wandered Deansgate and Shambles Square contemplating not the cool things like David Bowie and Roxy Music and perhaps the Crombie overcoat and Joy Division, but the Attica State massacre, political activist Angela Davis, and John Sinclair, all eulogised on that album and far more interesting and important. Wonderful, too, a little magical, because, having left school for a job in a factory, they inhabited a faraway kingdom. The album was packaged to look like a newspaper and its lyrics, printed on the sleeve, were its stories. This was a facsimile newspaper and I wondered at first, I said to John in the pub, whether you were real.

Those years in London are part of a larger, more complex picture. Often I am back with our cottage pie; often I am back in the normal house, in the kitchen where John is absorbed in another battered paperback, reading aloud a passage he admires. The image is static, a long distance telephone call in a storm. A black coffee sits on the table. Behind him the window and beyond it the boxy backyard inhabited by sun-bleached plastic chairs and children’s toys, perpetually observed through glass, becoming John and a metaphor for the strange distance in which we live our lives.

John Sinclair

October 2, 1941 – April 2, 2024

Notes

[i] Sinclair, John (ed.). ‘I Just Wanna Testify,’ It’s All Good: A John Sinclair Reader (London: Headpress, 2008), p.34.

[ii] Sinclair, John, ‘John Sinclair,’ Detroit, May 1, 1991. Reprinted in It’s All Good, p.21.

[iii] Burrough, Bryan, Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the Forgotten Age of Revolutionary Violence (New York: Penguin Books, 2016).

[iv] Sinclair, John, ‘It Knocks On Everybody’s Door: Detroit Sun Interview with Sun Ra, 48 E 3rd St. New York City. August 1966,’ Sun Ra: Interviews and Essays (London: Headpress, 2010), p.19.

[v] Ritsema, Mark, ‘The Blues of John Sinclair,’ It’s All Good, p.vii.

[vi] This part of the show was recorded at Eat At Jo’s in the Melkweg. The precise date is lost to my notes, but it was January 2008, a week before John headed to New Orleans for Mardi Gras, which he was proud to have attended most every year since the mid seventies.

- Other

- 1960s, 1970s, Abby Hoffman, Ain’t Nobody’s Bizness, Allen Ginsberg, Archie Shepp, Beatles, Black Panthers, Blues Scholars, Bob Seger, Borsci Elisir S.Marzano, Bryan Burrough, Cafe OTO, Caleb Selah, Cock Sparrer, COINTELPRO, Dalston, David Bowie, Days of Rage, Eraserhead, Geraldo Rivera, Gregory Ego, Haf-Fa Rool, Harlan Ellison, It’s All Good, Jair-Rohm Parker Wells, Jimmy Savile, John Sinclair, Joy Division, Keep It Together!, Kick Out the Jams, Leni Sinclair, Marshall Allen, MC5, Mezzogiorno, Mick Farren. The Deviants, Phil Ochs, Philip Larkin, Plastic Ono Band, Primal Scream, Radio Free Amsterdam, Richard Nixon, Roxy Music, Samuel Beckett, Smile Orange, Sometime in New York City, Stevie Wonder, Sun Ra, Sun Ra Arkestra, The Bowl, The John Sinclair Radio Show, Watergate, Wayne Kramer, White House Plumbers, White Panthers, William Burroughs, Yoko Ono

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress