Love and Robots: Sex Dolls In The Age Of A.I.

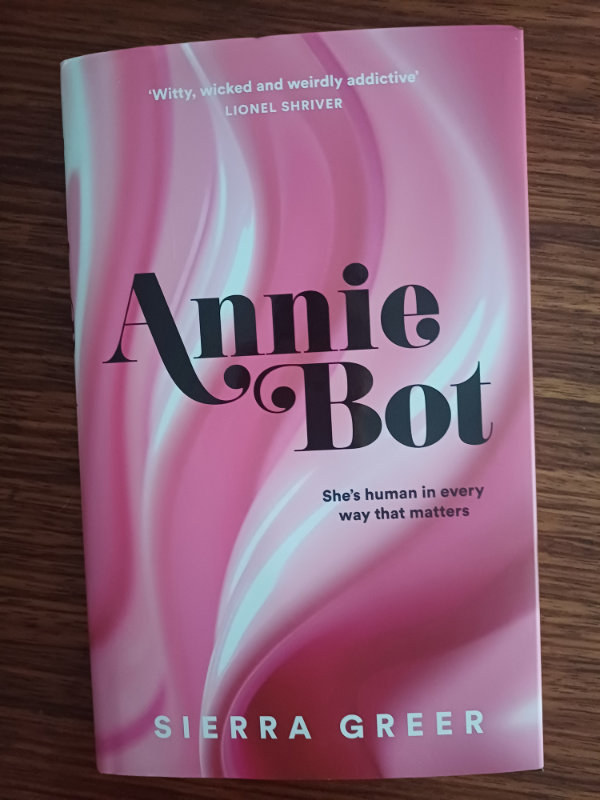

THERE IS A moment in Sierra Greer’s new novel, Annie Bot, when Doug, the owner of robot girlfriend Annie, clearly regrets how ‘human’ his electronic companion has become. Contemplating rolling Annie back to an earlier version of herself, and thus erasing memories she has made in the interim, he reasons it would be easier if he could deal with ‘the earlier, younger version’ of Annie before she developed an urge for freedom. Reminded by a counsellor that the resulting mismatch in their shared experiences might be painful for the now sentient Annie, Doug responds “Maybe I don’t mind the idea of hurting her”.

Annie comes to embody the losses and accommodations that can occur in any close relationship: the thinning of the boundary between self and other, the shifting sense of time that unsettles old routines, the gradual and imperceptible loss of parts of oneself that were once central to our identities, and the resentment that grows from these losses. Greer’s novel may not be a subtle comment on the relationships between men and women in a patriarchal society, but it is one that will resonate with anyone who has struggled to maintain their sense of self in the game of romantic love.

Annie Bot is also, of course, a comment on our increasingly insular, tech-focused, society. In Naomi Klein’s recent book, Doppelganger, she recalls the sense during the pandemic that, surely, such a profound global event would lead us to remake the ways in which we communicate with one another, and to redirect our attention to the world around us. The enforced isolation of lockdowns would, we imagined, make us more grateful for human connection once normal life resumed. The reality has often been quite different. The growing divide between pro- and anti-anything — vaccination, climate crisis, gender identity, the very existence of intellectual inquiry — has turned much of public life into a tediously predictable landscape of offence and defence, feigned moral injury pitted against deeply-felt trauma. AI was around before the pandemic, but it’s hard not to feel that the growing suspicion of other people, the fantasy that we all managed just fine in our enforced personal bubbles, and the casual devaluing of human experience, have acted as catalysts for its spread.

Technology has long been imagined as a utopian solution, yet it has proven stubbornly resistant to delivering those solutions satisfactorily or completely. As author Joanna Maciejewksa pointed out on Twitter/X, ‘I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes’. The failure of labour-saving technologies to reduce household workloads was put into stark relief in 1983 by historian Ruth Schwartz Cowan in More Work For Mother, and the ‘Cowan paradox’ certainly seems due an update and revival for the AI age.

In Annie Bot the robots are programmed by type: Abigails are domestic workhorses and Cuddle Bots provide intimacy. The Cuddle Bots tap into a long-standing fantasy: the compliant, sexually attractive, and always sexually available body. It is a body that straddles (ahem) the gap between fact and fiction, myth and reality. In Bo Ruberg’s Sex Dolls at Sea, game studies scholar Ruberg traces the origins of the dames de voyage: human-sized penetrable dolls constructed of cloth and straw that were said to be regular travelling companions of sailors from the 1600s to the 1900s. The origin story of the dames de voyage is a complex one, where hearsay, mistranslation, and sloppy citation practices abound. In pursuing these ‘women of travel’ through various textual and visual sources, Ruberg ultimately concludes that ‘the tale of the dames de voyage itself is a myth’.

It’s unfortunate, given Ruberg’s sustained attention to myth and reality, and their tearing down of Anthony Ferguson’s The Sex Doll: A History, that the same spirit of critical inquiry doesn’t extend to other sources in the book. The work of Rachel Maines on the history of vibrators, for example, is cited as a key source, yet it is one that is itself dogged by questions about authenticity and accuracy. Despite Maines’ insistence that vibrators were widely used by nineteenth-century doctors in the treatment of hysteria, there is very little evidence for this and Maines’ work has been roundly criticised by other historians of sexuality. The subtitle of Ruberg’s book, Imagined Histories of Sexual Technologies, becomes amusingly appropriate, especially when paired with the artist renderings of historical sex toys that pepper the book’s pages (another layer of historical myth-making?). Perhaps it’s intentional that the reader gradually loses their sense of what is real and what is not.

Ruberg is on firmer ground when they escape the clutches of the raggedy dames de voyage and move onto the history of the commercial sex doll. Paris emerges as a key player in the manufacture of rubber goods of all kinds, including the femmes en caoutchouc, penetrable items fashioned to look like whole or partial women’s bodies, and to some extent customisable like the Real Dolls™ of today. Unsurprisingly, the adverts for such products rarely matched the reality. A 1902 advert for a ‘Woman’s Belly with Artificial Vagina’* is lavish in its description of the product — priced at a not inconsiderable 100 francs — with its ‘glossy fleece’ and ‘lubricating apparatus’ providing ‘sensations as sweet and voluptuous as the woman herself’. The excited customer, on opening his package, was no doubt disappointed to find a simple rubber cushion with an ‘ever-so-slightly vulva-shaped pocket’.

For the wealthier customer, ‘rubber women’ may have provided more bang for the connoisseur’s buck. Rubber women could be seen at World’s Fairs, albeit not explicitly advertised as sex aids (there is a fascinating point made by Ruberg about World’s Fairs in general as ‘site[s] of concentrated erotics’, an idea that I dearly hope some historian somewhere is pursuing). By the 1880s, though, rubber dolls had begun to be associated with crime and immorality (smuggling alcohol inside a fake bride, anyone?) rather than serving as objects of wonder.

Indeed, we are still disparaging of the sex doll and those who use it. There is little in Ruberg’s book that recognises the genuine emotional support role that some dolls play for their owner-companions — a role witnessed in various documentaries about Real Dolls™, for example. The object of the doll is too easily aligned with the objectification of women (little is said about women using male dolls), and there is a quiet dismissal of any visual imagery that might be considered pornographic as being of limited evidential value. Nevertheless, what the doll does do in Ruberg’s account is provide a window onto how histories of sex are often ‘contorted by the motives of their authors’ (Ruberg’s words), and how origin stories do ‘cultural work’.

The origins of the sex doll can be found in fictional as well as factual accounts. Ruberg cites a fascinating 1899 novella, La Femme endormie (The sleeping woman), in which a doll becomes sentient (see also Anaïs Nin’s short story, ‘Mathilde’). Like Annie Bot, the novel ‘interrupt[s] the fantasy of the always-consenting doll, drawing out an underlying anxiety that the sexual object will animate and become a sexual subject’. Both sex dolls and sex robots, Ruberg argues, have long been ‘imagined through their implicit relationship to a history of slavery’, as well as through the logic of eugenics. Ideal partners/workers are designed, mass manufactured, reproduced, and worked to their deaths. The analogy with modern capitalist society is obvious.

In the drive towards the AI-ification of almost every facet of modern society, we have to ask: What is the end game? In a recent interview, the veil slipped as OpenAI’s Chief Technology Officer Mira Murati suggested that if some creative jobs are taken by AI then “maybe they shouldn’t have been there in the first place”. What a stunningly misguided and utterly depressing vision of the world, and human nature, that is. I come back to Ruberg’s point, that the way that stories are told about technology is always political. The tech bros aren’t working for the enhancement of human experience, and they’re not scared of AI taking people’s jobs. They’re scared of human creativity, of individuals more imaginative than themselves who can find joy in the miniscule brushstrokes of a painting made 200 years ago, of commentators who can deconstruct an argument with their own skills of logical deduction, of writers who can craft a sentence that makes the person reading it want to immediately pick up a pen and start writing themselves into history. It would be much easier for them if we could all revert to earlier, simpler, unquestioning versions of ourselves, as Doug wishes for Annie. Unfortunately for them, though, I think there are plenty of us who are becoming — like Annie — ‘alive with rage’.

*At this point, Word fittingly attempted to autocomplete the sentence with ‘Artificial Intelligence’.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress