In Praise of Noise: The Deafening Silence of the Pandemic

Opening a chapter of The Town Slowly Empties, an account of Covid in India, Manash Firaq Bhattacharjee writes:

I woke up late morning. Just in time to catch the cry of the vegetable vendor. It was a sudden, welcome reminder of the earlier life. The vendor’s voice sounded unreal, as if from another time. Did we switch back to the past?

Bhattacharjee beautifully pinpoints the power of sound to recall specific points in time, in this case a time barely removed from the present yet achingly out of reach. The pandemic has made the world a quieter place: between March and May 2020 the planet was quieter than it has been in recorded history, with a drastic reduction in seismic noise. The ‘anthropause’ has had a profound effect on wildlife, as animals have begun to venture onto deserted roads and into once-bustling urban areas.

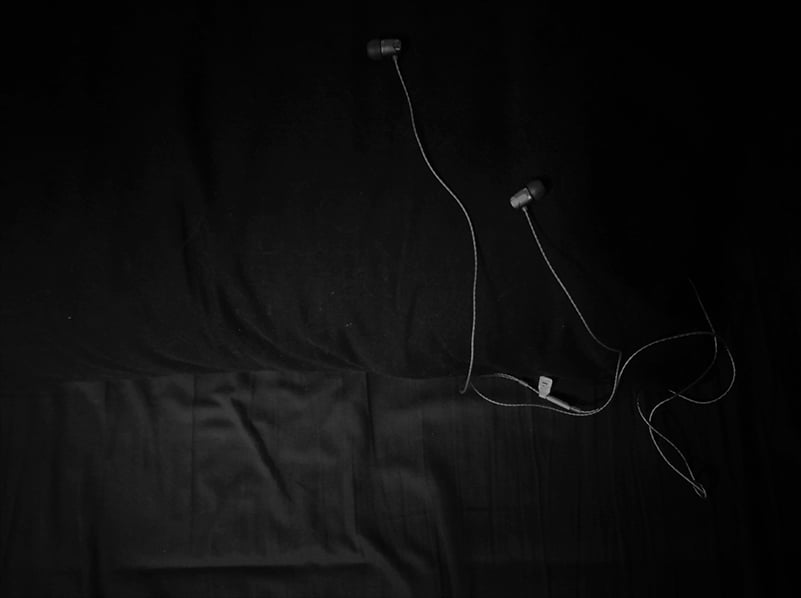

Comments on the ‘restorative’ impact of the pandemic, rhapsodizing about nature’s ‘recovery’ or the sudden tranquillity of empty streets, are not difficult to find online, especially from the first half of this year. But emptiness – whether spatial, temporal, or aural – is relative. It is, as the editors of Empty Spaces note, ‘something perceived through comparison’ and ‘highly subjective’. I was, until recently, very comfortable with silence. The hush of a library, the brief moments of solitude in a shared office, the moment of stepping from a crowded bus onto a deserted night-time street. Now, silence is unbearable. The moment a Zoom call ends, I’m compelled to fill the silence with music. I fall asleep with my headphones in my ears, waking up the next morning entangled in wires. The empty hours of the day are anxiety-provoking, too quiet and too sprawling.

Silence

Silence is never, of course, absolute. In Samuel Beckett’s The Unnamable the central character becomes obsessed with a search for ‘black’, total, silence: a silence that will be all-encompassing and authentic. The notion of silence as a valuable commodity pervades writings about silence and noise and, it seems, news about our current situation. Speaking to BBC Future about the possibility of a quieter world after the pandemic, psychologist Andrew Smith predicts ‘an adverse reaction to the return of noise – not just greater annoyance, but less efficiency at work, in education, in our sleep, as well as more chronic effects’. Personally, I can’t wait. There’s such a thing as too much silence.

In Sinister Resonance David Toop writes: ‘All silences are uncanny, because we have become estranged from absences of sound.’ Part of the uncanniness of silence is its ambiguous nature. It is ‘presence and absence, warm intimacy and chilling alienation’. We’re accustomed to thinking of silence in terms of reflection or liberation – as a blank background to meditation, or something to be savoured after a working day sound-tracked by the noise of other people. The practice of reflection works both ways, though, and my recent inability to cope with silence speaks more to morbid introspection than spiritual inner peace. Is this something to do with the quality of silence itself? In an article exploring silence (both verbal and historical) in Croatia, Jelena Marković asks ‘What is contained within the “emptiness” of silence?’ She goes on to consider how silence can signal stasis, burden, absence as well as presence. In hinting at what is not said, periods of silence within a conversation may be ‘full’, ‘charged’, or ‘ominous’. The aggressive silence of the pandemic has a similar weight.

I realise that it is neither the uncanniness of the silence, nor a sense of anticipation that something might happen to break it, that troubles me. Rather, it is the certain knowledge that nothing will happen. There will be no significant interruptions to the day; no one will call or text to suggest an impromptu drink in the pub; there is no need to remember your earplugs for that gig in the tiny venue with the massive PA system. The silence becomes an ever-present reminder of other absences, distances, and unmakeable plans. Lockdown has come to mimic the experience of depression, and depression’s tendency to destroy – as Andrew Solomon puts it in The Noonday Demon – ‘the ability to be peacefully alone with oneself’. It becomes harder to disentangle cause and effect. Is this depression or merely a perverse facsimile of it? There is a sense of standing outside everything, of inhabiting a space the boundaries of which can’t be breached without doing something calamitous.

I list the sounds that once structured the days: the click of heels on a quiet street as I leave for work early in the morning; the interminable and pointless on-board announcements of the 6:25 Oxford to London train; the fumbling of plastic coffee cup lids in the café at the end of the South Kensington tunnel. The sonic map that charted my way through the week has had its lines redrawn, its edges steadily moving inwards. As physical space has shrunk, the soundscape has shrunk with it. Leaving aside the new domestic noise of news updates and remote meetings that Marianne Constable credits with ‘transform[ing] what had been a domestic or personal retreat … into the center of a dangerously swirling world’, there is a sonic space to be filled. The silence is starting to develop form, edges, teeth.

Noise

Evan Eisenberg, in The Recording Angel, suggests that ‘[t]here is a bit of the survivalist in every record collector’. Records provide ‘sculpted blocks of time’ that provide a means of escape, sustenance, or restoration. The sound of a stylus touching the surface of a record is ‘a transformative sound,’ writes Toop, ‘a sound that dispels for a moment the visual, tactile reality of the present’. In place of coffee breaks in a bustling café my day is now punctuated by solitary listening breaks – 15 minutes of complete immersion in an EP or unpicking the minutiae of a live recording. I begin, for the first time, to catalogue my record collection: rediscovering forgotten releases, emptying out the contents of record sleeves, stumbling across handwritten notes from artist friends that underscore the sense of distance.

Music has become something grounding and tangible in a world become unreal. Noise smothers the silence, fills it up, contains it. The notion that music can have a profound emotional (and physical) effect is a long-standing one. Throughout history, a whole range of music from Wagner to Judas Priest has been condemned for its supposedly provocative, even pathological, properties. But, as historian James Kennaway notes in his book Bad Vibrations, music has also been celebrated for its capacity to stimulate and soothe the listener. In masking silence and quelling my anxiety I’m reliant upon rhythmic noise, techno, and power electronics, all of which have a simultaneous rousing and lulling quality. The intensity of a short, sharp, noisy, track is perhaps a perfect illustration of the quality that Vladimir Jankélévitch (in Music and the Ineffable) assigned to brief pieces of music: the intensity of the experience provides a stark contrast to silence. Although Jankélévitch saw this as heightening the listener’s appreciation of silence, there is surely something to be said, too, for intense noise as an antidote to unwanted silence.

There is something more than escapism and antidote here, of course. Music provides some connection to that which is absent: to friends, to pints in the pub before a gig, to the ears-ringing walk to the tube station afterwards. Eisenberg speaks of ‘ghosts’ in records – of long-dead singers making contact across the acoustic ether – but my ghosts are apparitions of the future. I make mental promises to the people I miss. When this is over, I’ll be at that gig even if I’ve been up since 5.00am. I’ll stay late for every club night. I’ll suggest we take an expensive trip up and down the country to see one 30-minute set. Because it is too quiet.

I couldn’t write this in silence. Thanks to:

ABSL – K

Fire In The Head – Confessions of a Narcissist

ILLNURSE – Unreleased

Iron Fist Of The Sun – Who Will Help Me Wash My Right Hand

Josh Hydeman – Screaming at the Wall

Ke/Hil – Syndrome/Antidrome

Salford Electronics – Communique 3

-

The Town Slowly Empties£9.99 – £20.00

The Town Slowly Empties£9.99 – £20.00 -

Fight Your Own War£9.99 – £25.00

Fight Your Own War£9.99 – £25.00

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress