The Silent Walk

It’s a vile Valentine’s Day evening, cold and wet, perfect conditions for contracting pneumonia. Yet the motley crew gathered beneath the Brutalist edifice of Kensington Town Hall remain stoic in adversity. A couple of volunteers wander through the crowd offering placards on sticks proclaiming:

‘Justice for Grenfell: We Demand The Truth’

‘United for Grenfell’

‘Tories Have Blood on Their Hands: Justice for Grenfell’

That last one is from the Socialist Worker. Their ‘Justice for Grenfell’ looks like a PS.

I resist the temptation of taking one in favour of keeping my hands in my pockets for the duration. In truth I’ve already chastised myself for considering the placards as potential souvenirs. The foul weather may have acted as a deterrent; it’s either that or the date, because there are plenty left in bin bags they can’t give away. One stalwart prepares to walk with a placard in each hand.

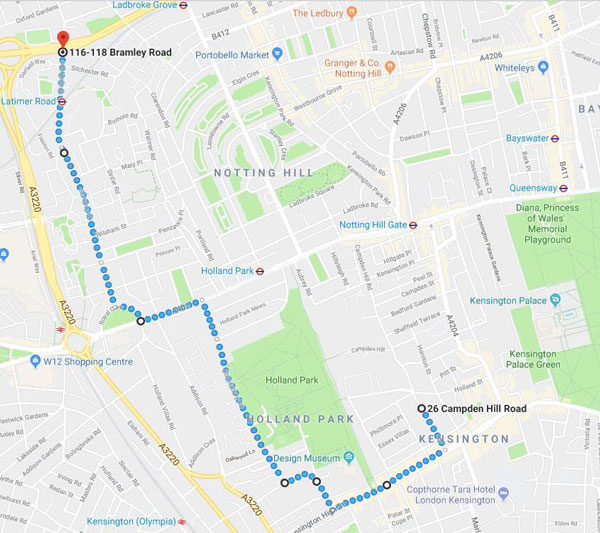

At 6 p.m. everyone dutifully files into the road behind a ‘United For Grenfell’ bumper banner, and the iconic green heart standards of the legion proclaiming ‘Unity’, Dignity’, Peace’, and ‘Just Us’, essential for the narrative because there will be no rallying cry until the end. This is a silent walk.

It is eight months since Grenfell Tower was consumed by fire. This is the first time the silent walk, held on the 14th of each month, begins from the council offices, the focal point of so much anger in the aftermath of the disaster. The media take their photos, film their footage, and with a combined police escort on foot and push bikes, the procession begins, bereaved at the forefront cradling the portraits of those they lost.

As an interloper I tuck myself into obscurity at the back. It is a memorial at the front, so bandwagon causes and dark tourists should be towards the rear. I don’t know if it’s strictly ethical for me to participate, but if it is, then I know my place. The Grenfell fire drew tourists and subsequent criticism. A sign appeared in the lobby at Latimer Road tube station, appealing for people to exercise restraint from photographing the tower where so many lost their lives, and residents made it clear they did not welcome selfie takers.

I have no idea if dark tourists have previously joined the walks, or whether there are others here besides me this evening. Last summer, when the memorial-cum-protest began, there would likely be those drawn by the immediacy to the disaster. Now, eight months on and in the barred teeth of atrocious weather, my attendance feels acceptable, to my mind at least.

There is no compelling reason for me to be here, other than dark tourism. But I’d specifically gone to see the tower before Christmas, discovering a charred blight, stark against the brilliant blue sky. The TV images desensitise. In real life the Jenga pyre slaps you in the face, you ‘get it’, and imagination does the rest. You have made a connection with the horror of being inside looking out, and being outside looking in.

A pair of crows took up residence on the roof of the shell as I stood on the platform at Latimer Road. They reminded me of vultures, minding a carcass.

*

The fire unfurled across my screen as I wrote about dark tourism into the early hours of 14th June 2017. It was still burning when I woke, and by evening the news teams had added the requisite pathos. A major disaster was unfolding on the other side of city.

The tower occupants had repeatedly warned of impending disaster, predicting it would take a ‘serious loss of life’ to expose the questionable practices of their landlord to public scrutiny. There had been ‘terrifying power surges’ due to faulty wiring, ‘residents had received no proper fire safety instruction’, and were calling on the landlord to ‘re-consider the advice that they have so badly circulated’, to remain inside their flats in the event of a fire. Residents warned such action would lead to certain fatalities.

A fridge freezer caught fire on the fourth floor of the twenty-four-storey block. By the time the fire service responded the flames had swept through a ‘chimney’ created by the cosmetic cladding, fitted during refurbishment the previous year, and the tower was ablaze.

This architectural facelift of the 1970s Brutalist block was primarily performed for the benefit of the Royal Borough’s wealthier residents, who saw the tower on the skyline when they visited the cheese sellers of Holland Park, rather than those in the community who called Grenfell home. The cladding was not considered fire resistant, and should never have been fitted to a high-rise. But it was a cheaper substitute than more suitable fire resistant cladding, by £2 per square meter, a total saving of £5,000 across the 129 flats.

The fire burned for sixty hours. The death toll was uncertain, eventually given as seventy-one. Ten months on it now stands at a minimum of seventy-two.

The estate surrounding the ruin is adorned with yellow ribbons tied around the trees and the street furniture. A shrine at the nearby Methodist Church is taped off to provide demarcation between mourners and the media. Forlorn teddy bears testify to the number of children lost. There is another shrine on the railings of Bramley House, and another beneath a protective gazebo thoughtfully erected in the elbow of the cut through beside Latymer Church. The brick wall backdrop is angrily signed, telling whoever is stealing from the shrine to stop. On boards covered with plastic to protect the handwritten sentiments and condolences, there’s a scrawl that says the fire was a Holokaustas of the Illuminati, a sacrificial offering to appease their reptilian goddess.

Under the Westway the cavernous space has been turned into an impromptu community centre in which to congregate, surrounded by mournful art and testimony, with a piano decorated with a portrait of Bob Marley, and somewhere to sit, a viewing platform of sorts, facing the tower.

Grenfell wasn’t a random act of terrorism, or a natural catastrophe, but something both predicted and entirely preventable.

*

Within twenty minutes one walker slopes off with his placard, back down High Street Kensington towards McDonald’s, although there’s a Five Guys just up ahead. To be fair I already wish I’d brought an umbrella. Layers of clothing merely postpone the inevitable as icy water trickles its way to the marrow. Our progress is halting, presumably as the police temporarily close the side-streets to allow us to pass safely. I exchange fortifying smiles with fellow walkers. One lady carries a bunch of red roses, another a small light box proclaiming, ‘Justice 4 Grenfell’. Faces glow, lit by lanterns, candles and green flashlights. A bedraggled whippet hangs on to his companion with a flashing disco leash.

A child in a pushchair wails in protest, but otherwise our assembly waits patiently in silence before shuffling forward again. People stare out from bus stops. Customers and staff gravitate towards the shop fronts to witness our progress. Residents from the flats above come to their windows and film on their phones, while at street level a documentary film crew tracks the procession from the pavement.

We turn off the high street and stretch our gait to ascend the rise and curve of tree-lined Melbury Road, towards Holland Park. Once away from the traffic amongst rarefied real estate the silence becomes deafening; the wet footfall, the plop of raindrops on brollies, and the torrent pouring over the grate into the sewers below.

I drift into the innards of the column in a futile attempt to find shelter behind a banner and a pair of fire fighters. Tall windows above our heads are blanketed in opulent drapes, betraying only the seductive glow of warmth within, excluding the miserable night without. The inhabitants of these properties swaddled in the millions do not come to their windows, save one. The chandeliers are off, but the lady is home. She looks down on our waterlogged train, a discreet silhouette in the darkness.

The silent walk has a cathartic quality. This is not a dark tourism experience like the walking tour organised by the 9/11 Tribute Museum. It is not meant to be. There’s no fee or commentary. We have not been invited to come and stare, just to walk in silence.

As a dark tourist I could be accused of tagging onto a grief bandwagon, here for the dead only because they died in a newsworthy manner. I could have looked up the names of those lost, yet didn’t bother. I didn’t feel it would validate my presence if I had.

‘Stamp out Racism’ have a banner here, although the fire didn’t discriminate. The walk has been politicised by the attendance of supporting groups, which in turn provides sufficient excuse for dark tourists, and consequently it doesn’t feel as if we are joining a cortège. These groups provide support to Grenfell’s silent walk, which will develop over time as more associated activism is drawn in behind their headline banner. It will be a symbiotic relationship; the interests will piggyback their respective messages and the walk will receive the impetus of fresh legs.

As long as those who instigated the walk retain control and their call for justice is the predominant message, then this phoenix will retain its powerful aura. Because there is something very special about this walk within this company that is indefinable, yet very real.

Sporadic disquiet comes from impatient motorists trapped in the side roads as we cross their junctions. They hush their horns when recognising the procession for what it is. Our route funnels us thinly against parked cars and stationary traffic. Motorists trapped behind sweating glass look up at us, their faces ethereal.

Fire fighters form an honour guard under the bridge at Latimer Road tube. A woman in the procession lays a blessing hand on each of them in turn, as if anointing, while others shake hands or bow their heads in acknowledgment. The walk comes to its conclusion in Bramley Road under the welcome shelter of the Westway, where everyone gathers to face the tower and to observe the call for a final minute’s silence. Grenfell Tower stands against the night, black on black, monolithic, ominous, alienated from the neighbouring sentinel blocks where there are lights, and people at home.

Tonight’s route was a fraction over two miles and has taken just over two hours. They say that over 1,000 people took part. That feels generous, but not excessively so, and it’s hard to tell for sure in the dark from the back.

Zeyad Cred, organiser of the Grenfell Silent Walk thanks everyone for the support, recognising that so many people frozen and wet-through just goes to underline their resolve. They will need it, because there’ll be many more cold wet walks in the years to come, long after the tower itself has been demolished and a memorial put in place. But they know they’re in for the long haul. Manchester staged a companion walk today, for which a round of applause is called for and received. Next month Bristol, perhaps Liverpool will join in.

Karim Mussilhy from Grenfell United says a few words, about how they are disturbing the peace with peace. Then there is a speech from ‘Lowkey’, a rapper and political activist who also witnessed the fire. He says the walk along High Street Kensington has interrupted and disrupted the flow of money. Someone tries to talk over the top of him. They say they’ve been coming for three months, that the organisers told them to stand at the back, so they stood at the back, but now they want to have their say. Someone tries to shush them. The camera pans away from the contretemps as Zeyad leads the walkers in a final rising chant of “Justice!, Justice! Justice!”

What would Grenfell accept as justice, and will they ever receive it? If it takes as long as Hillsborough, then I won’t be around to find out. And in truth I’d already slipped away for the warmth of the tube before they started their rallying cry. I watched the addresses delivered under the Westway, once home, on the Grenfell Speaks Facebook page, which streamed the walk in its entirety. I rewind and follow it from start to finish, but it’s not like actually being there. Next month, perhaps the month after, I’ll return and walk with them again.

*

The regular monthly peaceful protest of the Grenfell Silent Walk reminded me of Argentina’s Madres de Plaza de Mayo, where mothers gathered every week opposite the presidential palace, demanding answers for their children, who disappeared under the military dictatorship during 1976–1983. It is estimated that as many as 30,000 were abducted during this period, when belonging to a student union was considered sufficient provocation to warrant arrest, detention and death.

The mothers walked in protest every week from April 1977. Initially just fourteen, in pairs, as it was forbidden to walk in larger groups. They wore white headscarves, symbolic of nappies, bearing the names of their missing children. Their movement gained momentum and brought human rights abuses in Argentina to global attention, despite the loss of some founding members, who also disappeared, kidnapped by the military junta and thrown to their deaths from aircraft over the sea.

Pregnant detainees amongst ‘Los Desaparecidos’ were held until they gave birth, their baby then adopted by childless military couples, after which the birth mother was killed. Estimates suggest 500 children were ‘stolen’ in this manner. The grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, having lost their own children, set about tracing their unknown grandchildren.

After military rule ended in 1983, the mothers continued to campaign. Their efforts have resulted in 700 sentences being passed, with over 100 ‘stolen’ children being identified. Having walked for forty years, some now parade in wheelchairs, and the global media continues to recognise their commitment, presence and impact.

H.E. Sawyer is the author of I Am The Dark Tourist: Travels to the Darkest Sites on Earth. ‘The Silent Walk’ is not taken from that book, but is a standalone essay/observation.

H.E. Sawyer is the author of I Am The Dark Tourist: Travels to the Darkest Sites on Earth. ‘The Silent Walk’ is not taken from that book, but is a standalone essay/observation.

H. E. Sawyer

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress