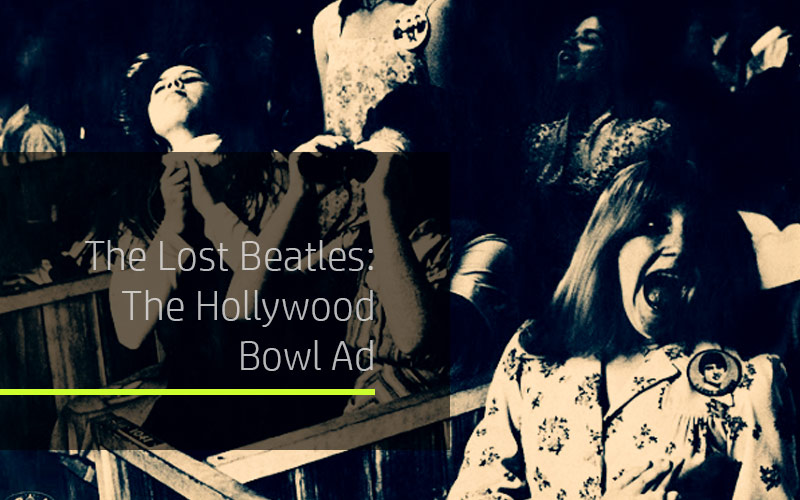

The Lost Beatles: The Hollywood Bowl television ad

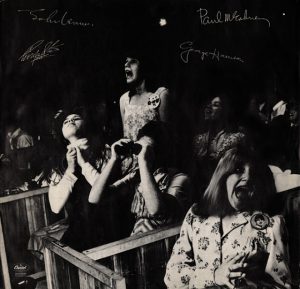

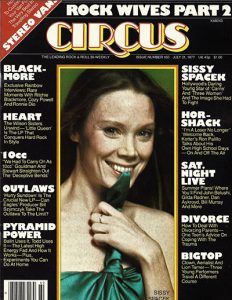

Record producer George Martin was asked by his young daughter whether the Beatles had been as popular as the Bay City Rollers. Probably not, he answered, which saved him a lot of explaining. The anecdote appears on the sleeve of The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. Journalist Lester Bangs repeats it for his review of the album in Circus magazine (July 21, 1977) but Bangs is not so accommodating. Bangs likens a Beatles performance to a ‘real Living Theatre’, the emotional unity between adoring fans and musicians akin to experimental theatre and the dissolution of the ‘fourth wall’. Yet, wrote Bangs, it was difficult to equate the Beatles phenomenon with the sound of this record, specifically the photographs of ecstatic faces on the inner sleeve. He asked readers to take the record from ‘inside the sleeve and play it, and wonder how what you’re hearing could possibly have inspired what you’re looking at.’

Beatles performance as ‘Living Theatre’

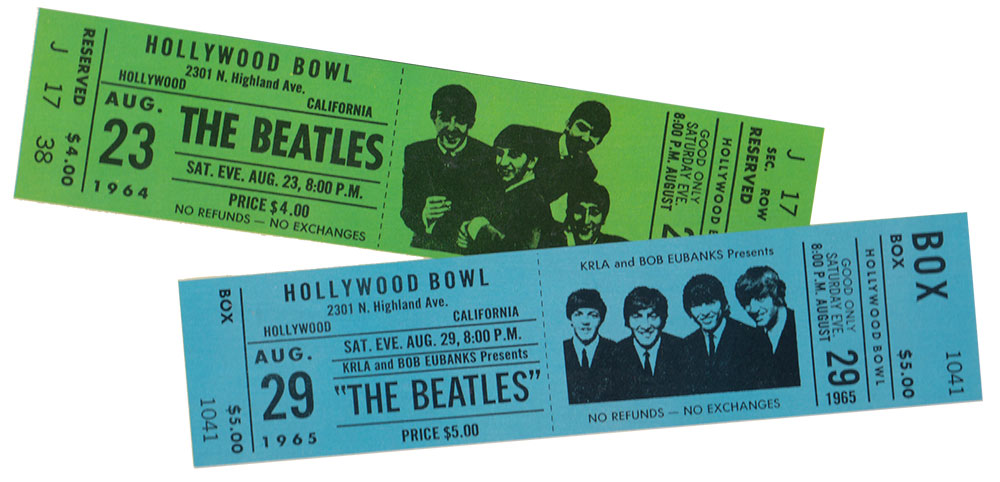

During the Beatles’ 1964 and 1965 American tours, Capitol Records recorded three performances at the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles with the intention of releasing a live album. But the quality was lacking, and the project was shelved until 1977, when George Martin remastered the tapes and compiled the best versions of songs into The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl.

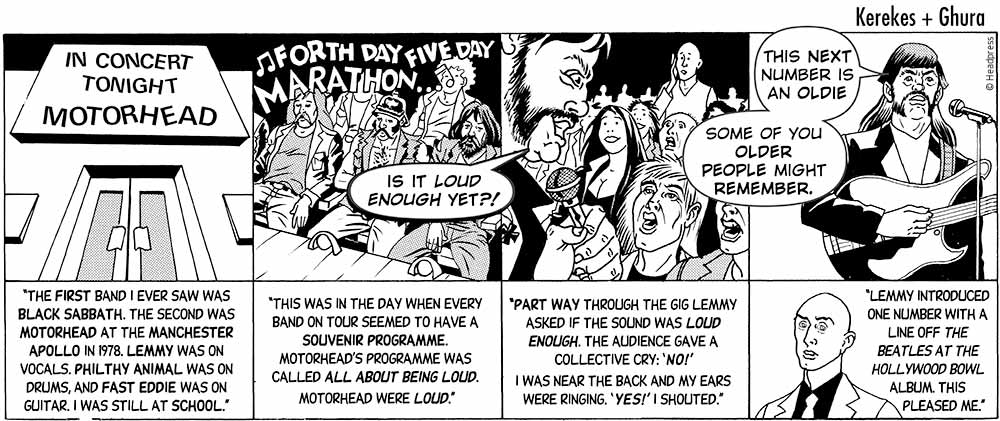

Motörhead expressed an interest in volume

In 1977 the Beatles as a creative unit had come and gone. The first UK Beatles convention was still a few years away and interest in the Beatles at my school was something uncool. The first concert I attended was Black Sabbath at the Apollo in Ardwick Green, Manchester. The second, also at the Apollo, was Motörhead. Patchouli and volume were the common denominator. Motörhead were promoting their album, Bomber. Lemmy asked the audience whether the sound was loud enough and turned up his amplifier in any case. Being loud was the deal. The Apollo, an all-seating venue, doubled as a cinema and, when the occasion arose, also featured CCTV from major sporting events. These were the days before satellite television and pay-per-view. Although I wasn’t much interested in sport, I recall ads for live screenings of Ali’s next big fight, usually in the early hours because of the different time zones. Even at a dozen or so rows back from the stage, the sheer volume of Motörhead rattled my ribcage. The souvenir programme—all major bands had one—was titled ‘All about being loud’ and in it Motörhead expressed an interest in volume. Ted Nugent, known for being loud, wasn’t loud— he wore ear protection. I found Motörhead irresponsible and exciting. But I liked it best when, during the concert, Lemmy started quoting the between-song banter from the Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. I turned to my pal, who wasn’t a Beatles fan, and tried to explain. But it was too loud.

Bangs, in Circus magazine, spoke not so much of the music contained on Hollywood Bowl — he says nothing about it at all, in fact — but rather the Beatles phenomenon as a ‘secret shared’: either you get the Beatles or you don’t. And getting the Beatles isn’t necessarily the same as liking their music. Bangs speculates how it must feel for the posthumous Fab Four, collectively revered but as individuals not so much, and quotes a statistic relating to the enormous sales of posters, specifically those of the Fonz and Farrah Fawcett. He uses this information as the media uses it: a cultural barometer of how famous the Beatles once were. But shifting units has nothing to do it. For Bangs, hearing Lennon introduce songs on Hollywood Bowl, which he does with humour and irreverence, ‘triggers vistas’. The Beatles, writes Bangs, seemed to be ‘code to a private, yet internationally shared, universe.’

A barometer of how famous the Beatles once were

I feel that was the case with Motörhead at the Ardwick Apollo, with Lemmy paraphrasing Lennon when introducing one of their own songs (Overkill). “This next song is an oldie,” Lemmy told the Manchester audience, “some of you older people might remember.” At school a small handful of friends were as obsessive about Beatles lore as me. They had other interests, but the Beatles were a litmus by which all else could be measured, so it seemed. I did not attend any of the Hollywood Bowl concerts. (Bangs did.) My Beatles experience is not lived experience in that respect, as I was rather too young for the phenomenon as it unfolded. The Beatles have always been history to me, and as history they remain both real and unreal.

What I did witness first-hand was the Beatles Renaissance, the reinvented popularity that has seen super deluxe album reissues, a videogame, and the Disney bankrolling of the revamped Beatles swan song Let It Be, released theatrically later this year. Arguably it started with The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl, which met with critical and commercial success on its release.

When the Beatles Book spoke of the 1965 US tour it was in its usual incumbent way. The fan monthly for all things Beatles offers a brief account of the Hollywood Bowl concerts in its twenty-seventh issue (October 1965). The concert on Sunday, August 29, the first of two nights at the Bowl that year, is said to have been preceded by ‘one of the largest and most efficient press conferences of the tour’ and an award of gold discs from Capital Records for Help! Nothing in the Beatles Book is likely to upset the lovable mop top image. The account continues with the boys being driven from Capital Records in an armoured truck, a fan in the Hollywood Bowl car park giving birth to a baby boy, and 17,999 people in attendance at the concert. There’s a nice moment in Ron Howard’s documentary Eight Days a Week. Among the celebrities who recount the impact the Beatles made on their lives, an interview with actress Sigourney Weaver cuts to b&w footage of one of the Hollywood Bowl concerts, the face of a little Sigourney Weaver in the crowd, caught by the camera in passing.

There are missing bits of this coded history

There are missing bits of this coded history. One is an ad campaign for the release of the Hollywood Bowl album which played on British television in 1977. The campaign, as I recall it, focused exclusively on the cacophonous roar of the crowd, an element as much part of a Beatles live performance as the music itself. One reason Capitol Records are said to have shelved the album the first time round was the poor quality of the recording. I wonder if by poor quality they actual the fans, the screaming permeating the album like a jet plane unable to take off. Some contemporary reviewers, Bangs among them, heralded this aspect of the album — the ecstatic fans — as important. The ad, which appeared on British television, showed no footage of the Beatles, as I recall, but instead footage lifted from b&w horror films of the silent era. The unmasking of Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera was among the clips, as I recall, so too images of mobs carrying flaming torches out for revenge. All of this was to the accompaniment of the Hollywood Bowl soundtrack — specifically the cacophonous screaming. I am at a loss to find any trace of this ad. Even in the age of YouTube and the Internet Archive there is no record of it, nor any reference to it.

Lester Bangs did not review the Hollywood Bowl album. He pointed at it and showed why it made no sense to compare the Beatles to the Bay City Rollers, or debate whether posters of the Fonz and Farrah Fawcett outnumber sales of Beatles records. What he was saying was that something more profound exists: a code, a secret shared, a television ad for The Beatles at the Hollywood Bowl. And that, at some future point, I would not find it.

Note: At the top of the page is a flavour of what the television ad looked like, a rough impression of what I recall of it. This is not an authentic ad but a loose facsimile. It includes the soundtrack of screams and silent film imagery. As noted, I am pretty sure Phantom of the Opera was in there. However there was no Lennon soundbite — that’s included for a bit of fun. The whole thing is a bit of fun but perhaps it might encourage further investigation or jog some memories.

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress