Ladies and gentlemen, the “practically unsinkable” man!

Picture the scene. It’s an autumn afternoon in 1883, and you’re walking down Exhibition Road in London. You enter the International Fisheries Exhibition at the north end of the street, the whole afternoon ahead of you. Inside is everything you could ever wish to learn about the fishing industry, life at sea, and marine flora and fauna. There is a bright aquarium of fishes, a pool of swimming seals, a flamingo pond, and – hanging over the central hall – a 60-foot whale skeleton lent to the exhibition by the Marquis of Exeter. After you’ve looked at the model of Canterbury Cathedral made out of 300,000 seashells, and had your fish dinner in the restaurant, you wander to the corner of the exhibition dedicated to life-saving apparatus. Standing in front of a display of inflatable waistcoats and cork jackets is a small crowd. Craning your neck, you see a smartly-dressed man giving a lecture, occasionally gesturing to a tank of water beside him. Pushing your way forward to get a better look, you find yourself fascinated and appalled by the sight within: a small dog, its mid-section ballooned to comical proportions, is paddling up and down inside the tank like a portly canine dinghy.

This was a demonstration by Henry Silvester, a Clapham doctor. He was most renowned for a resuscitation technique – the imaginatively-named ‘Silvester method’ – that compressed the chest by using the patient’s arms like levers. His work with inflatable dogs is, for some unfathomable reason, less well known. The dog in the tank was part of Silvester’s experiments into what he called “hypodermic inflation”. He was apparently inspired by an Assyrian monument in the British Museum that showed people crossing a river on inflated animal skins. By introducing air beneath a dog’s skin, Silvester suggested he had improvised a buoy: the dog appeared able to support its own weight in the water quite easily.

So far, so weird. Silvester wasn’t satisfied with a mere inflated dog, however. Surely, he thought, the same method could be used on men. He had seen cases of emphysema in his patients that had been caused by broken ribs: air escaped into the subcutaneous tissue and puffed up the patient’s neck “like an air pillow”. Just imagine: if there was a simple way of inflating a person, there would be an end to needless drownings – an inflated man would be “practically unsinkable”. Besides his animal experiments, Silvester went on to inflate a human subject at King’s College Hospital by introducing air beneath the skin of the wrist. But how to make the procedure easy enough that anyone could do it – if they found themselves in imminent danger of falling overboard a ship, for instance? Thinking back to his human “air pillows”, Silvester suggested that making a hole inside the mouth with a penknife (or the teeth) before inhaling forcefully a few times would get sufficient air into the subcutaneous space of the neck to keep a person afloat. It would be a “perfectly harmless and almost painless” procedure, he assured readers in an article for medical journal The Lancet.

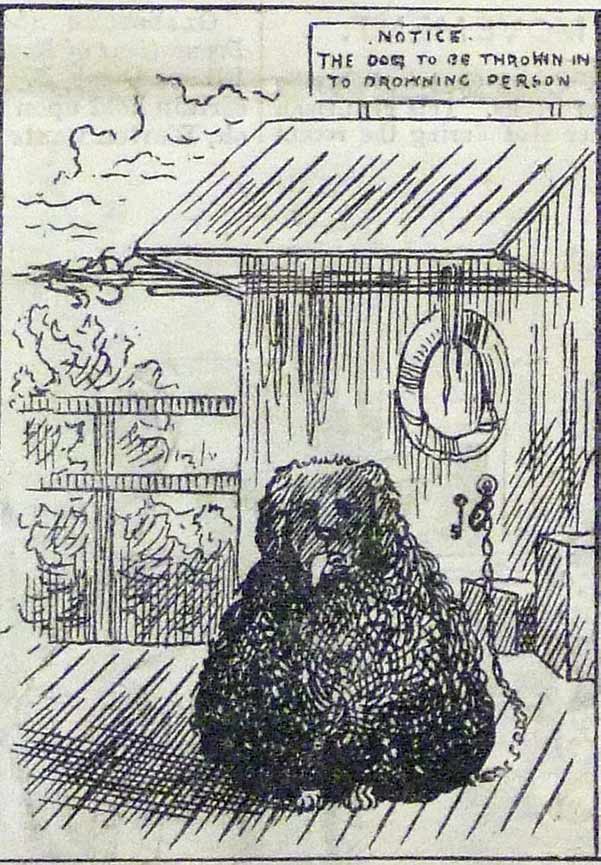

You might be unsurprised to learn that interest from Silvester’s fellow medical men was minimal. Where Silvester’s work got a fair bit of coverage, though, was in the comic and satirical press. Punch is perhaps the most well-known of the Victorian humour magazines, but there were several others, including Scraps and Funny Folks. Many of these were more free-form than Punch, kind of 19th-century versions of MAD – and they were quick to spot the comic potential of Silvester’s invention. Funny Folks ran a strip on the possible uses of the method at the seaside: inflated donkeys that could be ridden in the sea, and inflated life dogs to be thrown to swimmers in difficulty. Scraps envisioned a man self-inflating when his ship sinks. Having floated happily home through crashing waves, his sweetheart no longer recognizes her rotund suitor and flees in terror. Now a bona fide man of the sea, he returns to the waves to shack up with a beautiful mermaid. And in Gil Blas, a French literary newspaper, a fictional piece gave readers the basic instructions for self-inflation via one Commander Laripete, who tests out the procedure on himself. He balloons up to Mr Creosote proportions in his sleep, and it’s a somewhat horrific image: ‘The stomach of Laripete reached nearly to the top of the bed and his arms had taken such a swollen form that they floated above the sheets like balloons’. A doctor has to be called to deflate him.

There was a serious side to all this: more people were going to the seaside but couldn’t necessarily swim, and there were regular calls to put more life-saving devices at popular swimming sites like London’s Serpentine. It’s not clear how much readers of Funny Folks or Scraps knew of Silvester’s experiments, or how seriously they took the possibility of inflating themselves in a sticky situation. But I do love the fact that Silvester saw the cartoons as being of equal merit as newspaper and journal articles about his experiments: he pasted all of them into his scrapbook. I’m still not sure how seriously he himself believed in the prospect of self-inflation, but — regardless — don’t try this at home, kids.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress