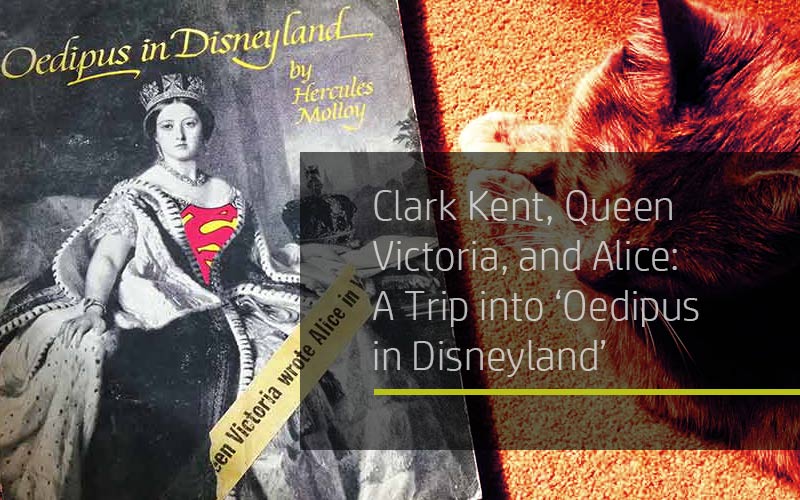

Clark Kent, Queen Victoria, and Alice: A Trip into ‘Oedipus in Disneyland’

We all have those books on our shelves that we bought solely because they looked like they were just out there enough to be interesting. Oedipus in Disneyland: Queen Victoria’s Reincarnation as Superman is one of these books, which I picked up at the Henry Pordes bookshop on Charing Cross Road in London about ten years ago. It had Queen Victoria on the cover, a Superman ‘S’ superimposed on her bosom, and the title was utterly mystifying. I had to buy it.

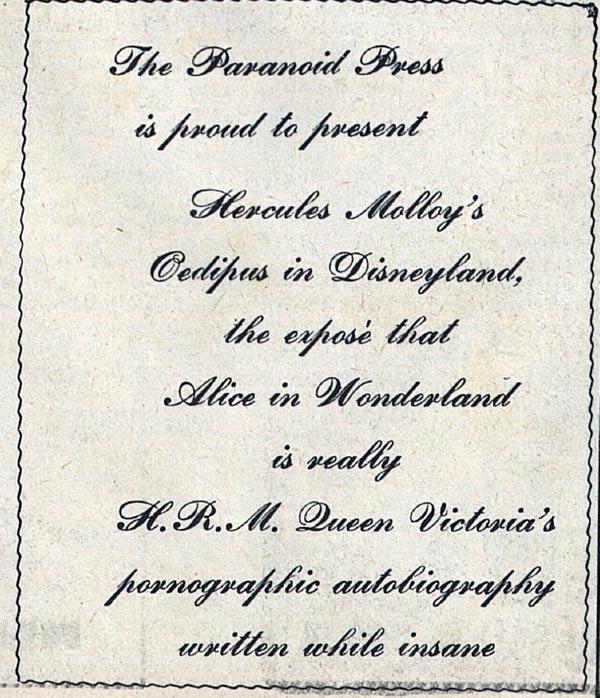

Oedipus in Disneyland was published in 1972 by The Paranoid Press, a press that – as far as I can tell – existed simply to publish this volume. Author Hercules Molloy, signing himself ‘Minister of U.S. Propaganda’, starts the book with a Foreword, Introduction and Prologue, all of which bamboozle more than they enlighten (though I am quite enamoured of his thoughts about tedious citation practices: ‘I won’t quote the pages, you arrogant, supercilious ignorant bastards! Fuck you’). Clark Kent is introduced as a ‘paranoid schizophrenic… The other half of his split personality is the famed American comic strip hero, Superman’. The Prologue, riffing off of McCarthy-era concerns about popular culture, has Chairman Mao and members of the Politburo in the Kremlin listening to the Minister of U.S. Propaganda as he explains that Alice in Wonderland is part of a ‘diabolical series of five-year-programs in sex education’.

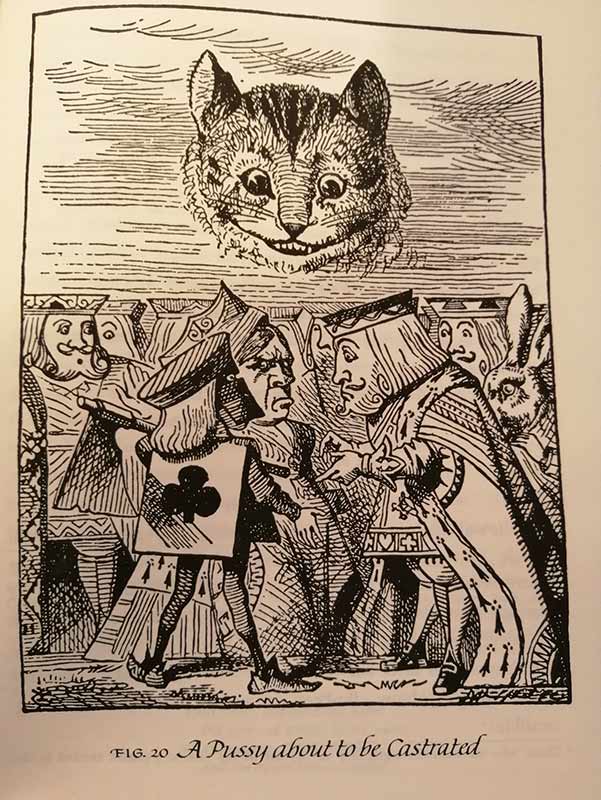

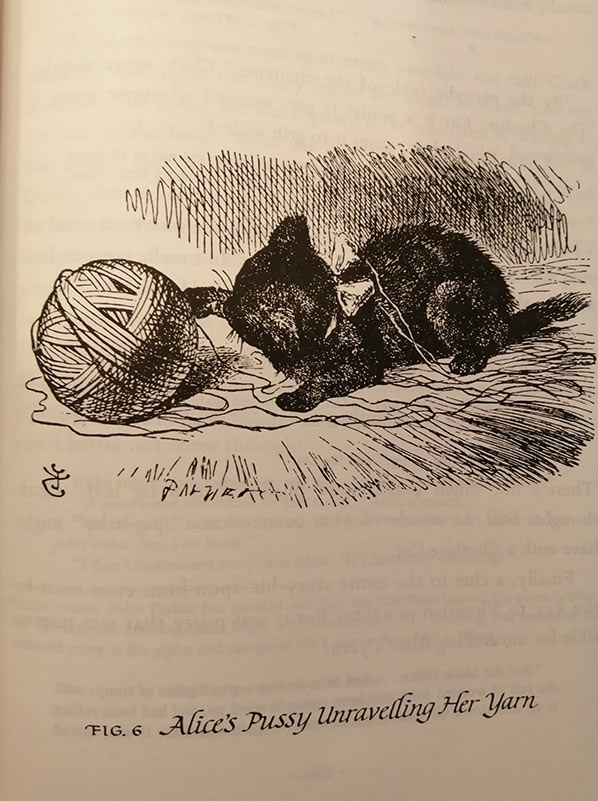

John Tenniel’s original Alice illustrations appropriated by Hercules Molloy.

The first part of the book sees Clark Kent indulging in copious amounts of sex and drugs after his graduation from Yale University. When his exploits land him in a Mexican jail, Kent spots ‘a fuck book’ lying on one of the beds in his cell, which turns out to be Alice in Wonderland. Kent then takes us on a whistle-stop tour of Alice, deconstructing the book’s ‘real’ messages with the help of Freudian psychoanalytic theory and uncovering the truth about the book’s author in the process. Alice in Wonderland was not written by Lewis Carroll, he realizes, but is in fact the pornographic autobiography of Queen Victoria! With me so far?

It’s nothing but a fuck book! It’s unadulterated pornography! If fucking’s dirty, Alice in Wonderland’s got to be the filthiest book around! It’s all about Alice’s pussy!

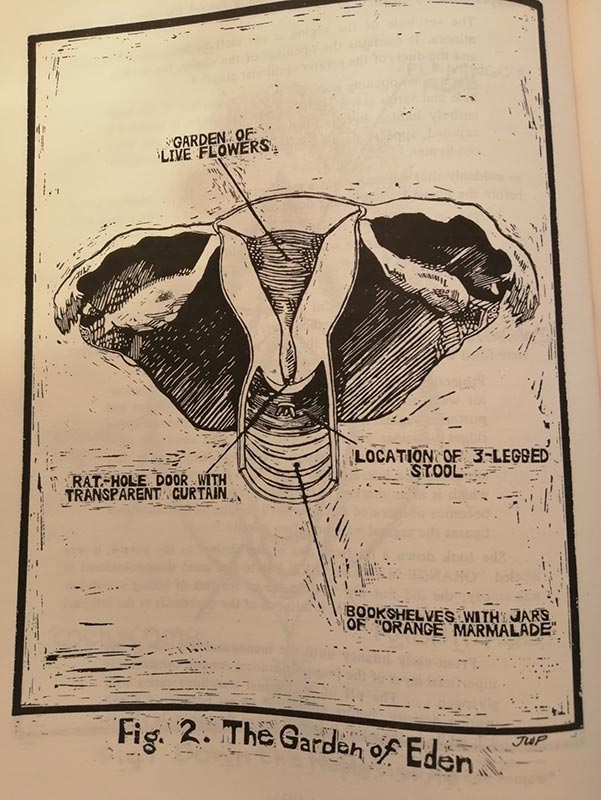

If you’re confused, imagine how I felt reading the whole thing. The text jumps – presumably intentionally – between the third and first person, and shouty sub-headings appear midway through paragraphs (‘SUPERMAN FIGHTS FOR MENTAL HEALTH’, ‘A GOOD, GOOD STORY’). References to pop culture are scattered throughout, from Robert Crumb’s Whiteman to the Little Blue Engine (the latter interpreted in a suitably phallic light, of course). As Kent deconstructs the hidden messages of Alice, it’s hard not to revel in the sheer unbridled madness of it all. The Dodo’s race is an orgy. The Cheshire Cat is a penis. The Rocking Horsefly is a sex maniac. The White Rabbit is Alice’s father image: ‘That’s why she follows him down her (*blush*) “rabbit hole!”’ The pig-baby is a ‘penis-child’. The croquet match is masturbation. Several of John Tenniel’s original illustrations are reproduced and re-captioned: Alice ‘Shaking her Pussy’, ‘A Pussy about to be Castrated’. Alongside the Tenniel illustrations are impressionistic diagrams of the female reproductive system labelled with the geography of Wonderland – you’ll never look at a jar of orange marmalade in the same way again.

What the hell did people make of this upon its publication? American Libraries journal described it as ‘an experience in the power of the word like unto the mad laughter of the Marquis de Sade contemplating the Mona Lisa while editing an incomplete volume of the collected and illustrated werke of Freud’. They recommended it to librarians who were fiction completists as well as ‘hardy acquisition people’. (A letter purporting to be from ‘John B. Quick’ of The Paranoid Press was printed in the next issue expressing disappointment that the journal’s review had, however, neglected to mention the main thesis of the book.) Penelope Balogh, reviewing Oedipus for the International Journal of Social Psychiatry (oh, how I love that a copy was sent to an academic journal for review), was less amused:

It is positively insulting to put these gorgeous drawings made by Tenniel for Alice in Wonderland into this vast paperback which, in places, is pornographic … balderdash in big print … I will not add to a Library but shall happily give [it to] my child patients to cut out the Tenniel pictures.

In Oedipus, Clark Kent surmises that Alice in Wonderland was ‘a secret message to some unknown reader across the centuries who one day would decipher [Queen Victoria’s] secret code and learn the real tragedy of her life!’ This theory isn’t confined to the pages of Oedipus in Disneyland. Although Hercules Molloy is (unsurprisingly) a pseudonym, the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction identifies him as San Francisco-based doctor and author Howard Thornton. Thornton presented his case for Queen Victoria’s authorship of Alice in a rather less eccentric vein in the 1980s, when he published Queen Victoria’s Alice in Wonderland (under another pseudonym, David Rosenbaum). This was later expanded and republished as Queen Victoria’s Secret, and the mantle has also been taken up by James Saint Cloud (is Cloud a real person, or is he Thornton as well…?).

Controversies and conspiracies surrounding Alice in Wonderland’s contents, and Carroll’s authorship, rumble on. But more interesting than the veracity of Molloy/Thornton’s claims, for me, is the presentation of his theory in a volume like Oedipus in Disneyland. It’s a smorgasbord of smut and earnest psychoanalytical theorizing, with flashes of comic brilliance, that adamantly refuses to make the reader’s task an easy one. Given that reading some of Freud’s original case histories can be a bit of a trip in itself (jewellery boxes as vaginas, thick woods as … well, what do you think?), the readings of Alice presented here aren’t that far out in comparison. Coupled with snippets of newspaper cuttings, fantasy anatomical illustrations, and Clark Kent, though, Oedipus in Disneyland becomes an almost hallucinatory journey.

For the determined scholar, Molloy includes a set of study questions at the back of the book that hold the promise/threat of a similar treatment of The Wizard of Oz:

If you take the “po” out of potatoes, you get “taters.” If you take the “to” out of tomatoes, you get “maters.” What happens if you take the “fuck” out of Wizard of Oz?

Answers on a postcard, please.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress