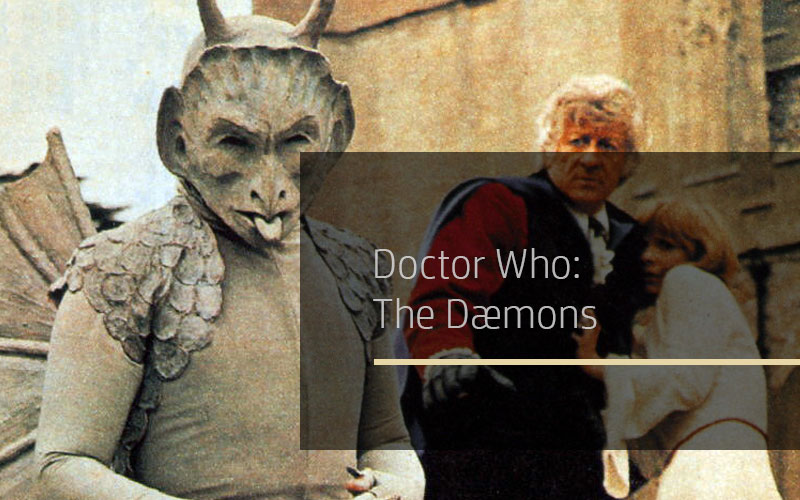

Doctor Who: The Dæmons

A televised excavation is due to commence at an ancient burial ground known locally as Devil’s Hump. A white witch in the nearby village of Devil’s End warns of terrible consequences. Fortunately, the Doctor is present when an invisible force field cuts the village off from the rest of the world. It’s up to him to break the spell the Master holds over the locals and thwart the overthrow of Earth by an alien entity that resembles the devil.

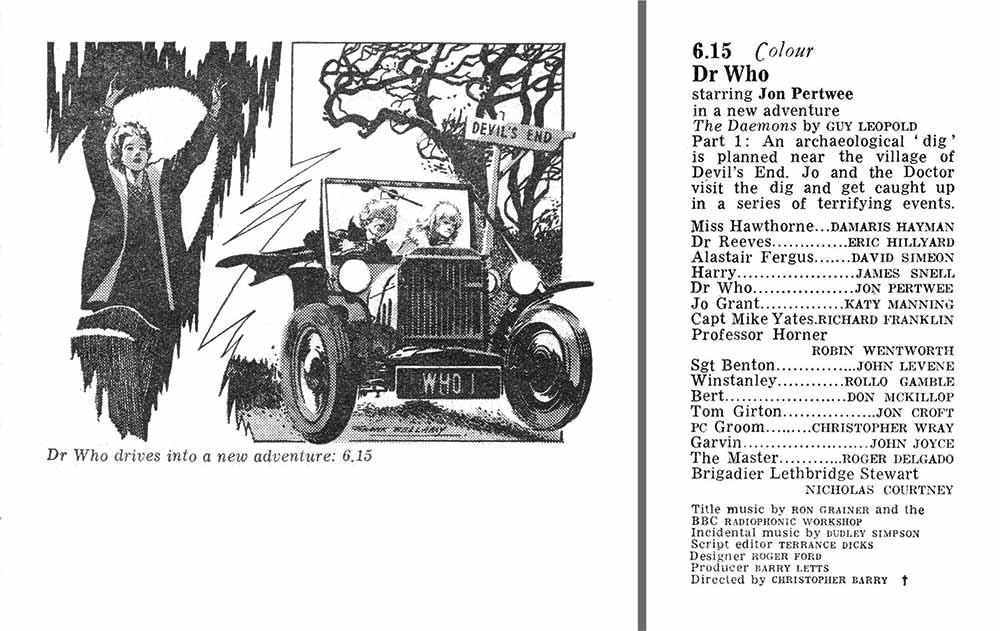

The Dæmons is a five-part Doctor Who adventure, originally broadcast May-June 1971, which stars Jon Pertwee as the Doctor and Katy Manning as his assistant Jo. The story by Guy Leopold (pen name for Robert Sloman and Barry Letts) borrows liberally from other fantasy sources, including the 1960 British movie Village of the Damned (adapted from John Wyndham’s novel The Midwich Cuckoos) and Arthur C. Clarke’s novel Childhood’s End. It also borrows from Nigel Kneale, the pioneering screenwriter who created Quatermass and a host of memorable television dramas.

Aside from this, The Dæmons is filled with occultist and magickal imagery that seems rather full-on in a show directed at children. When Robert Letts died in 2009, veteran of over 150 episodes of Doctor Who, his obituary in The Times singled out The Dæmons as ‘chilling’.[1] Doctor Who is populist television, arguably more so now than it was in the gung-ho 1970s, when it seemed for a time that all British television for kids was infused with weird or ‘dark’ elements, Catweazle (1970), Children of the Stones (1977), King of the Castle (1977), Worzel Gummidge (1979) et al. But what in the 1970s may have appeared on an even keel now seems almost capsized in the coldness of time. The rituals that take place in The Dæmons, in the basement of a church, are black masses in all but name, replete with cowled figures and the appearance of an enormous Baphomet.

These seas are choppy. The trilateral confluence of Nigel Kneale and prancing devils in a children’s drama is enough to set the good Doctor’s own head spinning. Which is one reason why, in this informal discussion, telefantasy expert and Whovian scholar Phil Tonge will be on hand to help dispense the smelling salts.

… Unfortunately, he can’t make it. Only minutes after receiving a copy of this article, before he was able to read it or add any comments, outside forces intervened and put the kibosh on that idea. ‘My PC has self-destructed,’ he texted me. We are on our own.

“I once switched on a Doctor Who and practically heard my own dialogue!”[2]

Nigel Kneale was full of mind-bending ideas and while he wrote for television and movies in a variety of genres, it is for his fantasy that he is best remembered. Like many pioneers, Kneale’s work has an almost precognitive order to it, in that what appears outlandish to begin with becomes in time the norm, helping to shape and define the culture around it. This might be because Kneale’s fiction takes a pinch of fact and peppers it with original thought. Modern ‘hauntology’ might said to have begun with him: In Kneale’s 1972 BBC play The Stone Tape, modern ghostbusters find that the spirit world is a series of events absorbed by place, traumatic incidents etched into walls like sound on magnetic tape. But while Kneale’s forte was the fantastic, he tended not to like other examples of it and he certainly did not like Doctor Who.

Writes Andy Murray in his biography of Kneale,

Kneale has famously lambasted Doctor Who for aiming to, as he puts it, “bomb tinies with insinuations of doom and terror.” He asserts, “Doctor Who was essentially a children’s show, put out at six o’clock. My own children were frightened, they really were. And I didn’t want to see that. I didn’t want to watch my children being frightened by some clown switching it on in a studio.”[3]

As Murray points out, this is rich coming from a man who himself had frightened half of Britain a decade or so earlier. Kneale’s six-part 1953 drama for the BBC, The Quatermass Experiment, is landmark television, in the way that the Beatles’ first appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show is landmark television, except that here a manned flight into space returns to Earth with a flesh-corrupting alien that promises to be the harbinger of human extinction.

It remains something of a conundrum that Kneale should hold the longest-running television fantasy franchise in such disdain. Murray notes that Doctor Who in the 1970s is ‘awash with recycled Quatermass plot devices’. Nowhere is this more apparent than in The Dæmons, which mirrors Kneale’s third Quatermass entry, Quatermass and the Pit, broadcast December 1958 through to January 1959. This too had begun with an excavation that unleashes a malignant force. So similar are the two that Murray likens The Dæmons to a Quatermass pastiche. Yet, adds Murray, it is inevitable that a crossover would exist in fledgling telefantasy. It might be argued that as much as Kneale was influencing Doctor Who he was also being influenced by it, wittingly or otherwise.

The Wicker Doctor

The Dæmons appears in Doctor Who’s eighth season. Setting aside Nigel Kneale, it is one of the story arcs with overt occult overtones and features a white witch (Miss Hawthorne, played by Damaris Hayman with customary dotty strokes). The setting is the fictional village of Devil’s End, a close-knit community with a Maypole on the village green. The Doctor is considered very much the outsider (called a “wizard”) and is unwelcome to the villagers, who are convinced he is a threat. At one point the Doctor is pursued, captured, and almost burnt at the stake. Watching this I was struck by the similarities to Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973), which The Dæmons pre-dates by a couple of years. The nature of the stories differ but underlying them both is this idea of blood sacrifice and totem secret.

The Doctor’s arch nemesis The Master (Roger Delgado) wins the confidence of the village in the guise of a parish priest. It is no coincidence he is around in time for the unsealing of the burial mound at Devil’s Hump, which takes place on the greatest occult festival of the year — a festival referenced on more than one occasion but never expanded on. He holds a ceremony to call forth Azal, last survivor of an ancient alien race that devours planets.

Film critic Leslie Halliwell has noted how Doctor Who was ‘much criticized for its horrific monsters, but they always moved very slowly’[4]. This is true. Azal is almost static. The horned god thunders on about what he intends to do, without doing any of it. He doesn’t venture beyond the basement of the church and yet remains an unsettling presence. This is often the case with cheap special effects and the ‘uncanny valley’ they inhabit, Azal clearly an actor in a costume with slit-eyes and plastic fangs. The actor behind the make-up evidently struggles with those fangs; they won’t keep still and cause him to drool.

The Dæmons offers two monsters for the price of one. Azal has a ‘familiar’ in the form of a gargoyle come to life, a creature with a fixed expression, whose tongue permanently juts from its mouth. It’s most effective when static and its first appearance, like that of Azal, is the stuff of nightmares. When it moves about it is not so good; it has a spring to its step, like a knee-slapping Dick Whittington in pantomime.

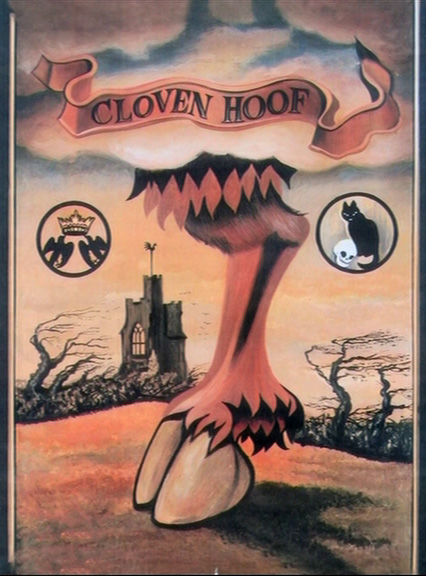

Barry Letts ‘had a fascination with black magic from an early age’, according to the booklet that comes with the BBC DVD of The Daemons. The story grew from an idea in which the Doctor confronts the devil itself, and seems more a mood piece, evoking paganism, black magic and folklore. The place names are not subtle: here is a burial mound called Devil’s Hump in the village of Devil’s End, whose local pub is The Cloven Hoof and nearby is something named Satanhall (a road sign says it’s 8¾ miles away).

The Dæmons is an unusual, gothic Doctor Who adventure. There is no TARDIS and science fiction is relegated to the periphery — literally, an invisible force field surrounds Devil’s End and a computer and berserk science are called on to penetrate it. The Doctor wouldn’t venture into this sort of territory often and not again until the Tom Baker-era Image of the Fendahl (four parts, October-November 1977). It’s nowhere near as good, yet the shadow of Kneale is again present in a story that involves ancient evil and white magic. The witch in Fendahl is played by Daphne Heard, another broad caricature, and one that steals the show. Most everyone else spends their time entering rooms and exiting them, somehow avoiding the plot and each other until the very end.

The final shot in The Dæmons pulls away into the sky to reveal a balmy English pastoral. Morris dancers and Maypole dancers (the Doctor among them) are on the village green. Panning back further we see the residents of Aldbourne itself, the village where filming took place. It’s a lovely, earnest moment. It acknowledges the façade while at the same time is cognizant of place and its own permanence within that place. Nigel Kneale did not like Doctor Who. One senses that he thought it somehow beneath him, this humble show for children. However, no one who wrote fantasy for television after Kneale could pretend he hadn’t been there first. In a way The Daemons is a fine pastiche, in that writer Robert Letts channels Kneale through a kaleidoscope of his own ideas.

[1] Anon, ‘Barry Letts: Actor and television executive who wrote, directed and produced more than 150 episodes of Doctor Who between 1967 and 1981,’ The Times, October 26, 2009

[2] Nigel Kneale quoted in Andy Murray, Into the Unknown: The Fantastic Life of Nigel Kneale (revised & updated) (Oxford: Headpress, 2017), p.162

[3] Andy Murray, p.126

[4] Leslie Halliwell with Philip Purser, Halliwell’s Television Companion, Third Edition (London: Grafton Books, 1986), p.222

-

Into The Unknown£9.99 – £25.00

Into The Unknown£9.99 – £25.00

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress