Taking Tobe Hooper’s Comment That Watergate Inspired ‘Chain Saw’ and Running With It

A friend of mine has a theory about Forrest Gump. It’s kind of brilliant.

“Forrest Gump was a serial killer who took on his victims’ lives,” my friend claims. “The box of choc-o-late was poison. Unreliable narrator.”

If you humor my friend, he’ll fill in details for you.

“He took his mama’s house, Jenny’s son, Bubba’s livelihood, Lt. Dan’s legs,” he explains. As further evidence, he’ll remind you how Forrest “led a group of disciples into the desert… and left them there,” a reference to how the character abruptly concludes his years of running near the end of the story.

My friend’s tongue is firmly in cheek, to be sure. But still, it’s fun to jog behind him down that weird interpretive highway. The further he goes, your faith in his vision can’t help but grow stronger. Soon you’re a believer.

Forrest is a maniac!

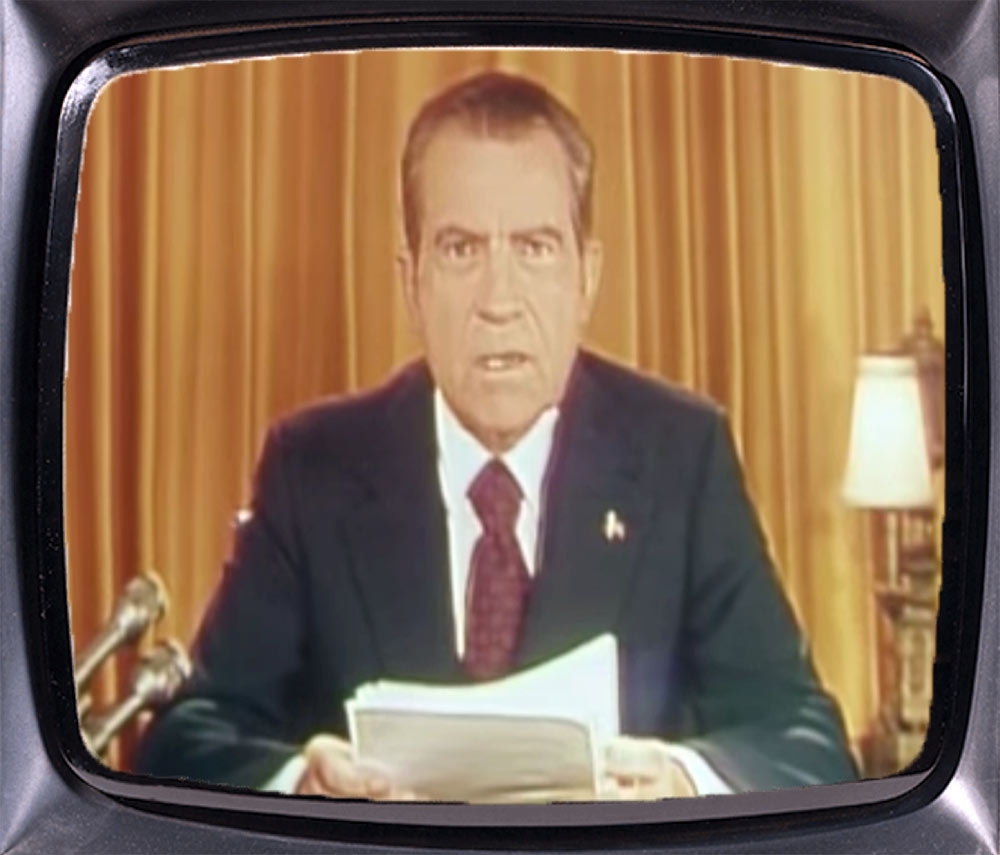

A corrupt U.S. president and a chainsaw-wielding murderer

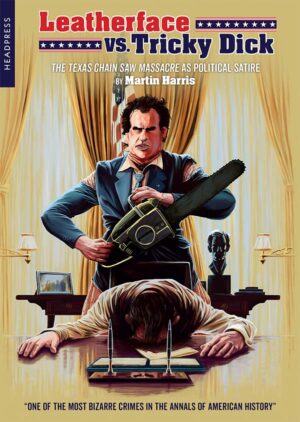

At first glance, my book Leatherface vs. Tricky Dick: The Texas Chain Saw Massacre as Political Satire might appear a similar exercise, a kind of aggressively idiosyncratic reading of the film that likens a corrupt U.S. president to a chainsaw-wielding murderer.

Early in the book I do refer to so-called “immersive criticism,” a term Chuck Klosterman has employed to describe a type of response that seeks to shoehorn a film into a particularly strange or unexpected interpretive box. The category includes conspicuously outlandish readings of films based on especially thin evidence (or none at all), a type of response most viewers rightly dismiss as fanciful.

For instance, you’ve probably heard of the inventive reading of The Shining as representing Stanley Kubrick’s confession he helped fake the moon landing. It’s an entertaining and inspired approach that nonetheless forces upon the film not just one but multiple subtexts that are certainly untrue. That’s not to say such a reading doesn’t uncover items of interest and even thematic relevance. But it does require a suspension of disbelief that resembles what creators of fiction often require of their audiences.

Political allegory and comedy

By contrast, seeking political commentary in Chain Saw isn’t nearly as great a stretch. In fact, the filmmakers themselves encouraged such a reading with their own comments about inspiration and intention.

Director Tobe Hooper frequently alluded to Chain Saw’s political messaging, both when making the film and when discussing it later.

“When we were talking about the film, Tobe always considered it a political allegory and comedy,” recalls cinematographer Daniel Pearl, as reported by Gus Hansen in the latter’s Chain Saw Confidential. Hooper echoed that point in commentary he recorded for Chain Saw a couple of decades after the film was made.

“This film kind of came out of the Watergate times,” says Hooper. “It was kind of inspired by it, in a lot of ways.”

Hooper’s collaborator Kim Henkel who co-wrote the screenplay would confirm such statements about the thinking behind Chain Saw. As one later feature on the film put it, “To the film makers, it was the blackest of black comedies, with some wry commentary on what Henkel called ‘the moral schizophrenia’ of the Watergate era.”

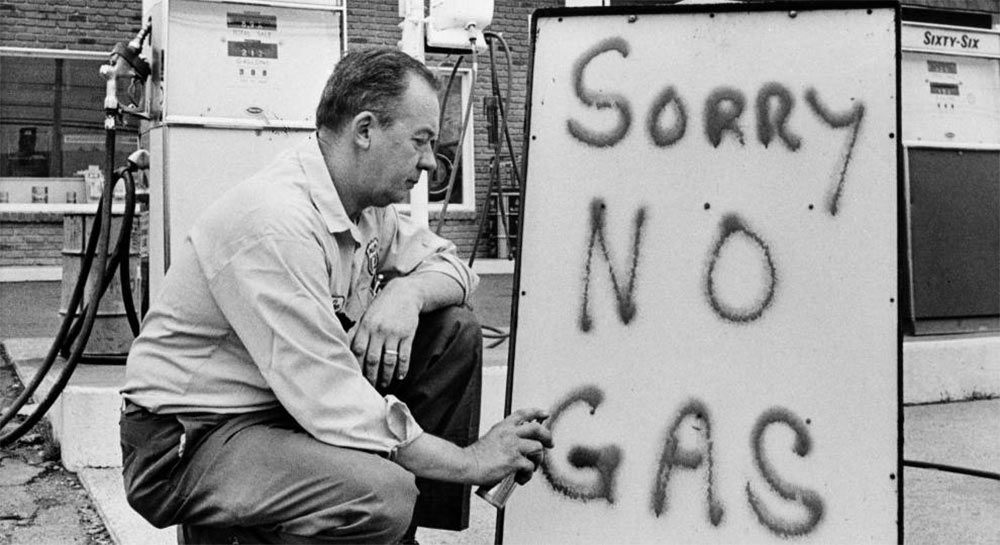

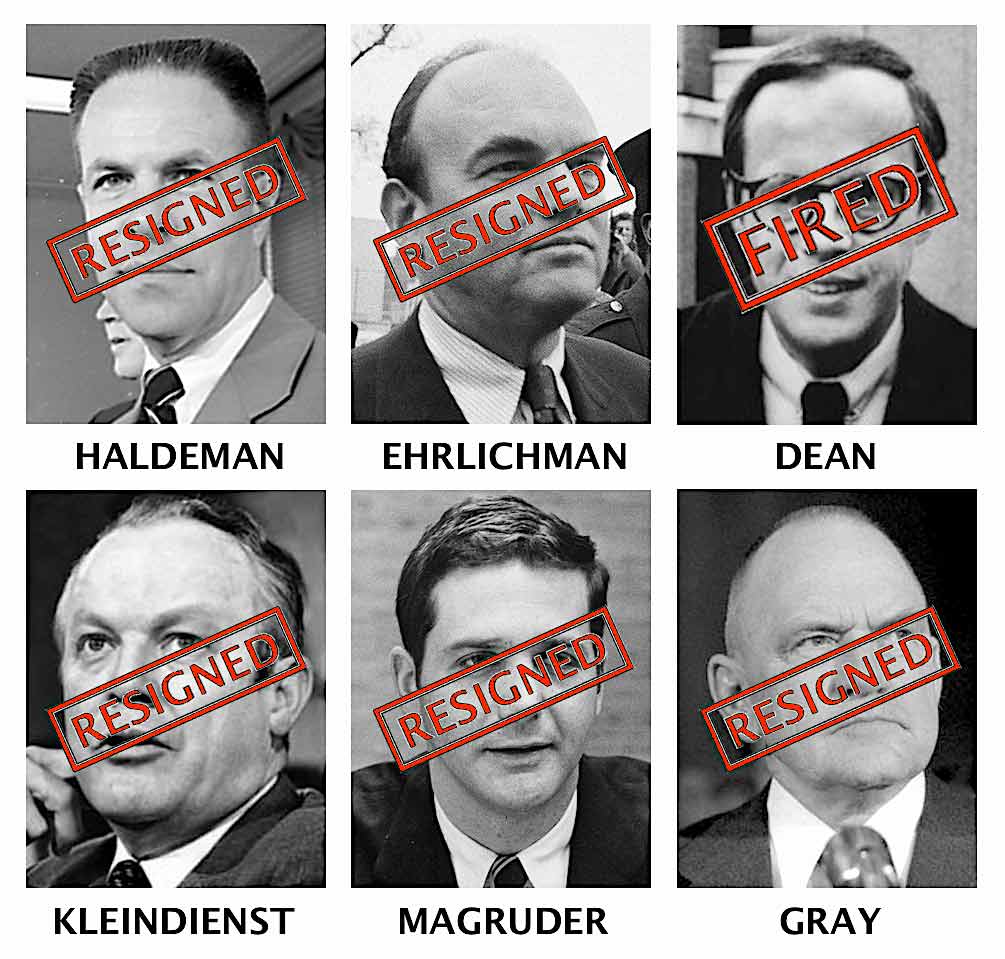

Saturday Night Massacre

Hooper first conceived of Chain Saw in late 1972, shortly after Nixon’s re-election. He and Henkel wrote the screenplay during early 1973 when the Senate Watergate Committee first formed and stories of the break-in and cover-up began taking off. The film was shot during the late summer while the hearings captivated millions and new revelations dominated headlines.

Editing and post-production took up the rest of 1973 and the first few months of 1974, a period when Americans continued to be shocked by events like the “Saturday Night Massacre” (Oct. 1973), the “I’m not a crook” press conference and discovery of the 18-and-a-half-minute gap (Nov. 1973), the indictments of the “Watergate Seven” (Mar. 1974), and publication of the Nixon-curated White House Transcripts (Apr. 1974).

As impeachment proceedings began (in May), All the President’s Men was published (in June), the House Judiciary Committee voted in favor of three articles of impeachment (in July), and the “smoking gun” recording was made public (in early August), the filmmakers worked on and finally secured a distribution deal for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. After Nixon resigned in August and was pardoned in September, the film was finally released in October.

In other words, “the Watergate times” formed an immediate context for the entire project, from the moment the idea for The Texas Chain Saw Massacre was first envisioned right through to when the first audiences saw the finished product. Meanwhile the film itself includes dozens of references supporting Hooper’s suggestion the scandal “kind of inspired” the film, too.

Some of these allusions are conspicuous. In fact the very first words spoken in the film, a radio news report, appear to be an unsubtle allusion to Watergate. “It is believed that the indictment is only one of a series to be handed down as the result of a special grand jury investigation,” says the announcer.

Other references are less explicit, including the implied “political allegory” likening Leatherface and his family of co-conspirators to the president and his men whose criminal behavior thoroughly traumatized an American public represented by poor Sally, Franklin, Kirk, Jerry, and Pam.

Reading Watergate

When it comes to the film’s political references and themes, Leatherface vs. Tricky Dick tries to explore all of them, and then some. It’s a minute-by-minute dissecting of Chain Saw that seeks and often finds evidence to support the filmmakers’ claims about wishing to provide a kind of “wry commentary” on a contemporary political crisis.

I think most will agree it doesn’t require a Forrest-Gump-was-a-serial-killer-sized interpretive leap to find that the makers of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre were more than a little politically aware. And while their primary purpose was certainly to scare the holy hell out of their audiences, it’s pretty clear they also wished to criticize a corrupt government and through satirical means comment on the grievous harm it had inflicted.

Some claim seeking subtexts in this way takes the fun out of horror. For many, though, doing so can provide another way to enjoy a film, especially one they have seen many times before. That said, I won’t be bothered if when you consider how much mileage can be gained from someone trying to “read Watergate” into Chain Saw, you find yourself asking a question once asked about Forrest Gump.

How far can he run?

-

Leatherface vs. Tricky Dick£11.99 – £25.00

Leatherface vs. Tricky Dick£11.99 – £25.00

Martin Harris

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress

2 responses

The Forrest Gump theory is marvellous – it has rendered the film watchable for me. And that is the point, isn’t it? Interpretation is a wonderful exercise, a parlour game. It’s as if we are telling ghost stories, jokes or tall tales to each other – alternatively think of the ancient Greek ‘cafe society’, entertaining each other with satire, the most outrageous point of view delivered convincingly. The object of the exercise is to offer the most convincing theory. The Shining moon-landing idea, though tiresome, delivers the knockout punch through manipulation of internal evidence, which may be entirely circumstantial – Danny ‘lifting off’ from a launch pad and journeying to Room 237. You’ve seen the sequence maybe dozens of times, and to suddenly perceive what in retrospect seems like a blatant signpost has the same thrill (greater, even) of reaching the climax of an impeccably contructed twist short story, or murder mystery. Kubrick subscribed to the ‘when you say what it means, it means nothing’ school, therefore his films demand interpretation, and their ambiguity and openness allows for a multiplicity of readings. That said, some interpretations are more compelling than others. The thrill of discovery is part of it, too – this stuff is distinct from Freudian, Marxist or Feminist ‘readings’ of films, though not so far removed as rarified academia would admit. ‘Reading’ in a similar way to palmistry, Tarot cards, Runes, goat-intestines or whatever other organising principle one uses as a repository of faith. ‘Meaning’ isn’t an inherent quality, the signal-senders intentions may be rendered screwy and subject to much noise-interference by the receiving apparatus.

My point, you say? I cannot lay my hands on the exact quote, my files are currently being reorganised, but a line I can attribute to Hooper sticks in my head. Something about him declaring he is ‘not really a political filmmaker’? Something like that. ‘Course, Hooper was but one of my many on the TCSM crew, and others may have had other ideas, Hooper may even have been being revisionist himself. I do recall, though, that Joseph Lanza spends a chapter expounding on the Watergate-Chainsaw Massacre parallels in his TCSM book – the theory is interesting, credible and persuasive but not entirely convincing.

I’m fine with contemporary political themes being perceptible in genre films – as I say, it’s entertaining and a stimulating intellectual exercise (similarly, I know some who maintain certain films predict the future!), but it isn’t the whole story, and I find it limiting. When i was a youngster, I swallowed all the chatter about fifties sci-fi being cold war communist paranoia. But because I was young, these ideas were rather abstract to me anyway. I love Invasion Of The Body Snatchers – when I watch it know, I think ‘how dull this great film seems when considered solely as an allegory for a specific historical political moment’. Those things are something to consider. But films that are obviously allegorical of their time can only seem kitsch in retrospect.

Joe Lanza makes hay about jim Siedow having a ‘Nixonian’ grin – maybe. I’d rather reflect on a more expansive film – with it’s indelible, incredible image of bone-monuments, remarkable, primitive music score, an apocalyptic journey more compelling than the bloated, worthy ‘The Road’ (first the gas runs out, then the descent begins into a pervesely mannered savagery (crumbling white houses (that plays into your theory!))), the savagery of the frontier so reudely sidelined by AMerica’s children of affluence … Our hero, Leatherface, is much the product of neglect and abandonment …

I agree 100% that the film is a black comedy – feminist nightmare comedy … The sexual politics should be rich pickings for todays commentators – it’s an alternate reality, a world without women that poor Sally Hardestry and her mystery machine chums tumble into – somewhere where the south thought it never fell, like The Bed Sitting Room’s Queen of ENgland presiding over a landscape of broken crockery and gutted washing machines …

It is the true Scooby-Doo movie. It’s a gosh darn work of art. We got the best of it in England. The film was so potent, it couldn’t be shown, but the title alone was like a magic spell – that particularly conjunction of words compressed an instant-movie into the mind. My friends and I were fascinated. It also carried the ominous weight of something completely forbidden. It was tantamount to crime, sin – something unspeakable and sordid. We discovered this creature ‘Leatherface’, and with only these meager raw materials we understood. One day at school, my friend told me about TCSM2, how it was banned (no idea how he found out this information, we were about 8 or 9 years old), and how there was a sequence in which Leather face takes his chainsaw to a posh car – a Rolls or similar. The picture it created in my ehad stays with me to this day. I somehow got the idea that in TCSM2 Leatherface arrives in Beverley Hills, or maybe well-to-do areas of Dallas or Austin, and goes on a binge of destruction. Beautiful, bright sunshine, green leaves, well polished car, sparks spewing off the metal work as the teeth of the chain saw chew into it, Leatherface’s mask a putrid patchwork of moldering, decaying flesh.

The (callous) old saw about flamboyant criminality being just another facet of american celebrity is done to death, but we know that every idea has an afterlife that goes many times beyond redundancy into a kind of Zen-zombiehood in contemporary culture. Maybe this will have a positive effect, and rob the horrible of it’s cloak of dark glamour. Or maybe it will destroy us all. The Biden-burp is but a pacifying salve. Janus’ head will spin again! Leatherface for President! Bone chairs in the White House. (And after that, Regan McNeill as the first Lady Prez).

Thanks for letting me on a spew-spree. i’m going to buy a copy fur shaw!