‘This happy place’: The uncanny appeal of The Sentinel

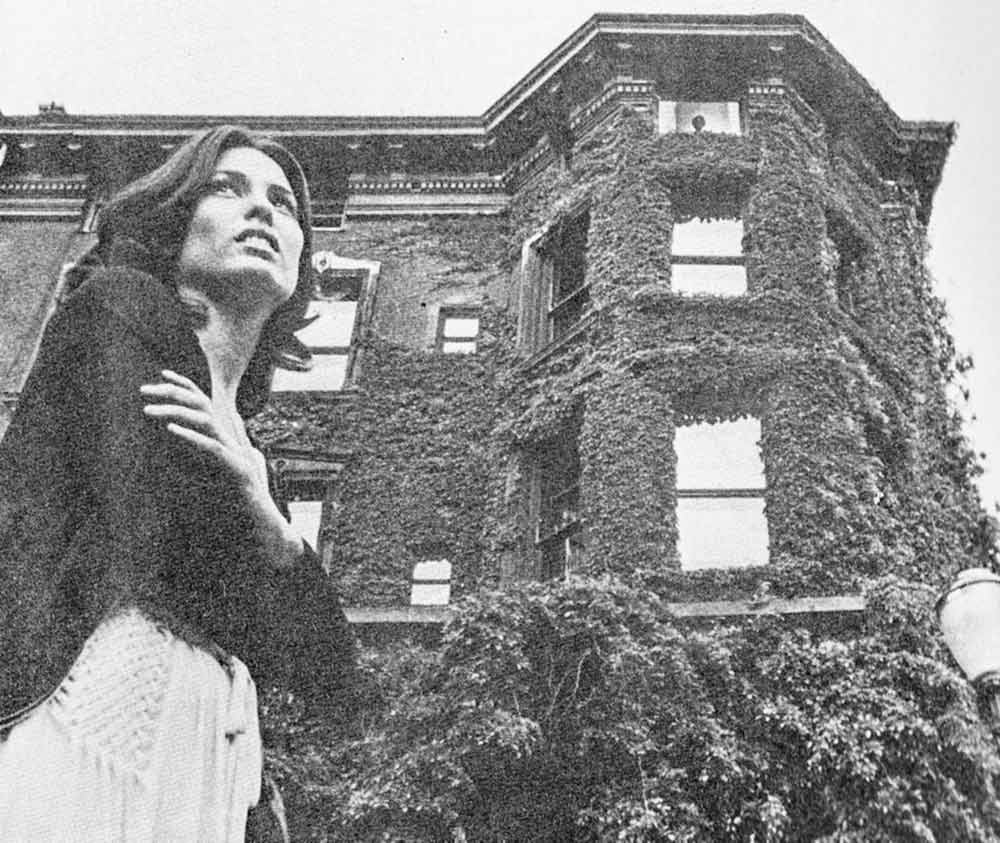

Two or three times a year I watch The Sentinel, the 1977 horror directed by Michael Winner and based on Jeffrey Konvitz’s 1974 novel. The Sentinel’s heroine, model Alison Parker (Cristina Raines), moves into a grand New York apartment to make a fresh start following a suicide attempt. All is not well at 10 Montague Terrace, however. Alison is plagued by eccentric neighbours, unexplained noises, and flashbacks to traumatic events in her past. It transpires she is to be the next ‘sentinel’, guarding the entrance to Hell that is concealed within the unassuming Brooklyn brownstone.

It’s not a flawless film by any means, but I love it. It’s one of those films that I put on when I feel a bit out of sorts and want to watch something comfortingly familiar. I know every twist of the plot, every scene, but it still holds my attention. I’m possibly in the minority here. Phil Hardy, in the Aurum Film Encyclopedia, bemoans Winner’s ‘clumsy sensationalism-at-all-costs direction’, calling the film ‘heavy-handed and mechanical’. In Nightmare Movies, Kim Newman likens the film’s ‘tastelessness and pretension’ to Burnt Offerings (1976), both films described as ‘the dregs of a genre more or less created by Roman Polanski in Repulsion’.

Okay, I’m not about to argue that The Sentinel is highly original, but to me it is more than mere schlock. Scottish film writer Brian Pendreigh is more on my wavelength: he calls it ‘genuinely creepy and arguably underrated’. Why is it that I find myself coming back to this film again and again, immersing myself in its familiar malevolence?

‘To this happy place, no evil thing approach or enter in’

Following an establishing shot of ecclesiastical goings-on in rural Italy (surely obligatory in occult-themed films of the 70s), the action switches to New York’s Central Park. Unsubtle contrasts – old and new, beauty and ugliness – permeate The Sentinel. The first few minutes of the film see Alison and boyfriend Michael Lerman (Chris Sarandon) viewing apartments, with Alison keen to secure a place of her own. The doomed apartment on which Alison finally settles is in stark contrast to Michael’s bright and modern bachelor pad. The exterior of the imposing brownstone is covered with ivy and accessed by a heavy wrought-iron gate; inside are polished wood staircases, chandeliers, and surfaces strewn with fussy ornaments.

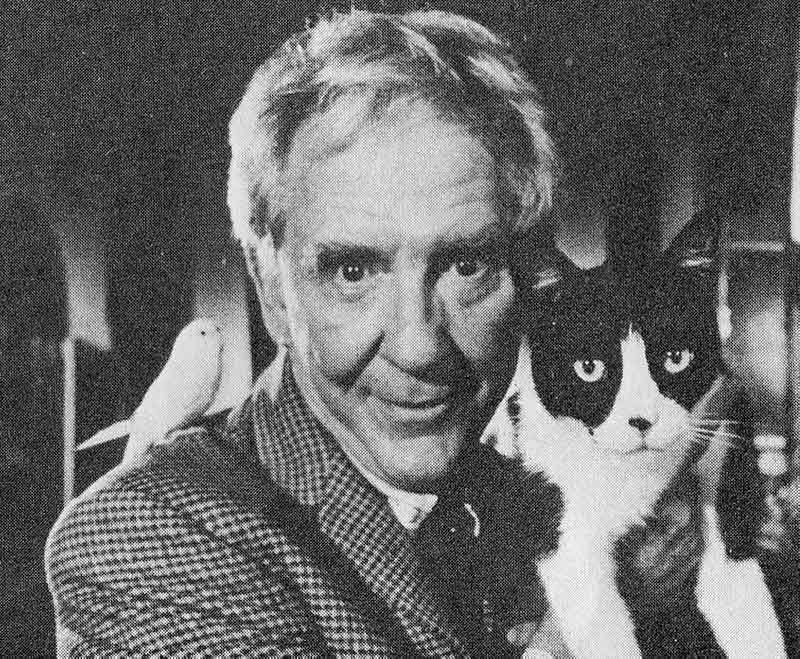

The building mirrors Alison’s family home, where – in a flashback a mere 10 minutes into the film – we see the teenage Alison walk in on her father, cavorting naked on a bed with several women and gorging on cream cakes. It’s the first of several truly weird and unexpected scenes in the film. Later, Alison attends a party for neighbour Charles Chazen’s cat. The black and white moggy, disgruntled in a paper hat, presides over a table that groans under the weight of drinks, cake, party hats, and noise-makers.

Chazen, played by Burgess Meredith, is a standout of the film: cutting, impatient, and shameless in his fascinated poking about in other people’s homes. Alison’s other neighbours include the sinister couple Gerde and Sandra (Sylvia Miles and Beverly D’Angelo). Miles would describe her character as ‘a mad, dead, crazed German zombie lesbian ballet dancer’ – and if that doesn’t make you want to watch the film then I don’t know what will. There are plenty of familiar faces joining Meredith and Miles. Christopher Walken, though he has very few lines to deliver, stands around looking charismatic; Ava Gardner swans about looking glamorous; Jeff Goldblum is harassed and moody, and Arthur Kennedy characteristically condescending. The least interesting character is boyfriend and lawyer Michael, whose arrogant self-assuredness is slightly annoying. Indeed, Alison’s glamorous circle of New York friends begin to look positively dull compared to the charming Chazen and his gossipy familiarity.

It’s within the old, ivy-clad house that Alison seems increasingly at home. The sense of the uncanny is nodded to in the tourism posters that decorate Michael’s hallway, beckoning travellers to a place where ‘you can be comfortably not at home’, somewhere ‘foreign but familiar’. The consistently blurred lines between the familiar and the unknown, and reality and imagination, in combination with the surfacing of traumatic memories, turns the film into a kind of Freudian nightmare.

‘I am one of the legion’

In a contemporary review in Films and Filming, Gordon Gow described The Sentinel’s shocks as ‘blood-freezers’: ‘a series of knowing jabs to the psyche’. Indeed, the film contains one of my favourite jump scares, second only to that scene in William Peter Blatty’s Exorcist III (and similar in its execution). Exploring the empty apartment above hers (in the middle of the night, in her nightdress – hey, I didn’t say the film was original), Alison lets the light of her torch play across the empty room. We wait for the moment when something horrific is illuminated in its beam, but it never happens. Only when the camera has panned back to Alison, do we see a silhouetted figure in the doorway that promptly strides across the room and disappears through a door on the other side.

The stop-motion quality of some of the effects adds to the film’s off-kilter quality: a nose is cleanly sliced through like butter, Michael’s face is suddenly ravaged, whip-like, by bloody scars. Films and Filming, on location in 1976, was spot-on in describing The Sentinel as an ‘out-and-out Grande [sic] Guignol horror movie’. Seen through the Grand Guignol lens, the film’s in-your-face effects and mutilations make a little more sense.

It’s the climactic scene, though, that generates most critical comment. Chazen summons up the demons of Hell to thwart Alison’s appointment as the next sentinel. They crowd the hallways and staircases, leering at Alison with twisted grins as they reach out with scaly, peeling, hands. David Robinson, writing in 1977, seemed particularly struck by this demonic ‘parade’. He pondered how the film would have turned out had Don Siegel (said to have considered directing) been at the helm instead of Winner:

‘It is hard to imagine how his version would have turned out, but it is reasonable to suppose that he would have treated it with a more sophisticated scepticism; that he would have made it sinewy where Michael Winner’s film has the awful pappiness of decayed flesh; and that he might have left something to the imaginations of his audience, instead of leaning so heavily on the special effects men with their confections of spurting wounds, slashed off noses and disgusting plastic surgery for the parade of hobgoblins at the end of the film.’

I’m not sure if Robinson appreciated at the time of writing that many of the physical conditions depicted were real: Winner had cast people with physical disabilities and facial differences (including Bob Melvin, best known for his part in the 1981 mondo doc Being Different). Several contemporary reviewers dismissed the film as ‘exploitative’ for this reason. ‘Offensive and repressive’, said one; a film for people ‘who like to slow down and look at traffic accidents,’ said another. One reviewer, more honest than most, said he would have viewed the casting of people with genuine disabilities differently had it been a Fellini film. It can’t be disputed that the demons of The Sentinel look, from our modern standpoint, spectacularly misjudged. It is a near-perfect example of the ‘Othering’ of physical difference that Martin Norden describes in The Cinema of Isolation (1994): disability and difference as a signifier of evil. At the same time, I’m cautious of simply assuming exploitation, which we could argue is a form of ‘Othering’ in itself.

‘Enter into full bliss’

Like Audrey Rose (also 1977, also based on a popular novel, also in my opinion under-rated), The Sentinel has an understated flair. It’s a stark contrast to the brash slashers that would follow in the 1980s. It has its problems, like many other horrors of the era, but it’s not bad. To some degree, I suspect the bad feeling directed towards The Sentinel is a consequence of who its director was, a sense of distaste that Winner was somehow encroaching on horror territory that wasn’t his. There are several beautiful sets and shots; some serious 70s fashion eye candy; an incredible cast of larger-than-life characters, and some wonderfully creepy moments. Watch it and be uncomfortably charmed.

- Reviews: Film

- 1970s, Aurum Film Encyclopedia, Ava Gardner, Beverly D'Angelo, Bob Melvin, Burgess Meredith, Burnt Offerings, Chris Sarandon, Christina Raines, Christopher Walken, Don Siegel, Exorcist III, Jeffrey Konvitz, Jennifer Wallis, Michael Winner, Repulsion, Roman Polanski, Sylvia Miles, The Sentinel

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress

One Response

Thank you for a very enjoyable article. I have a long and complicated relationship with The Sentinel. It has the same hold on my imagination you describe here. The simplest way to describe it is that The Sentinel has a genuine sense of the uncanny, a dreamlike quality many films aspire to but few achieve. It’s not terrifically original, being an amalgam of Polanski’s apartment horror (especially Rosemary’s Baby) and the likes of The Omen and The Exorcist. It seems to have a strongly reactionary morality as well – I think this is just Winner playing the genre as he thinks it ought to be rather than a heartfelt cri de couer. (Make that definitely). Anyway, this quality adds to the appeal in a strange way. In a very old fashioned way, it suggests that our time on this earth is brief and subject to all manner of worldly corruption. Get thee to a nunnery. You realise eventually we are all living our own Haunted House story. Winner’s unsubtle approach puts him more in line with some of our continental favourites rather than the American way of horror (which, with it’s projectile vomiting and glass pane decapitations is hardly genteel anyway). It’s certainly a film that gave us the creeps and fascinated when we were kids, so Mike must have been on to something. In a roll-call of big budget late seventies horror (Eyes Of Laura Mars, The Legacy, The Manitou, Prophecy, The Amityville Horror(s), etc), it ranks highly. That dreamy disconnect – Nights Of Terror (Burial Ground) has it as well – gives it an off-kilter feel that some more overtly surreal films don’t achieve.