Hoagy Carmichael’s Music Shop

Nearing 30, Wall Street stockbroker Hoagy Bix Carmichael knew it was time for a change of career. Something more worthwhile, a vocation. He had resisted any expectation that he would follow his father into showbusiness or a musical career, figuring one famous member of the family was quite enough. But during his college years in Los Angeles, he had acquired valuable experience in Hollywood working as an assistant to Burt Lancaster on films such as Elmer Gantry, and some sources say he worked as an assistant director for Columbia Pictures and Universal Studios.

In the late 1960s, WGBH was a Public Service Broadcasting Company based in Boston with a growing reputation as one of the most progressive in the US. Hoagy Bix had found the answer to his dilemma, and he travelled to Boston to volunteer his services. His prior experience in the movie world ensured he was snapped up, soon becoming an on-staff producer.

His father, Hoagland (Hoagy) Howard Carmichael, had been one of America’s best-known singer/songwriters since the 1920s; world-famous for jazz and Tin Pan Alley standards such as ‘Stardust’, ‘Georgia On My Mind’, ‘Heart and Soul’, and several hundred more during his long career.

While studying law at Indiana University in 1922, Hoagy Sr. befriended famed jazz cornetist and composer Bix Beiderbecke who inspired and encouraged him to write music instead. Bix proved such an influential figure in his life that Carmichael named his eldest son in his memory; Beiderbecke died of pneumonia aged just 28 in 1931.

In 1968 Hoagy Jr. met WGBH’s resident ‘music man’ Monty Stark, a 28-year-old white Oklahoman tasked with recording a big-band style theme tune for their new public affairs TV programme Say Brother. By, for, and about African Americans, it was the first of its kind in the US and is still running today under the title Basic Black.

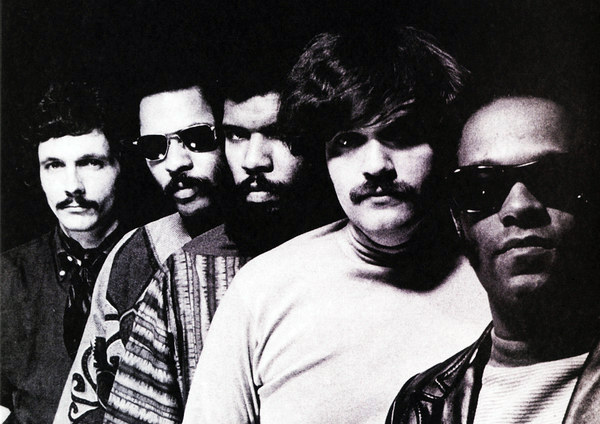

Stark, a graduate of Boston’s Berklee School of Music, was well acquainted with the local jazz scene. He set about forming a multi-racial jazz-funk group for the job. Christened the Stark Reality, this early incarnation consisted of 9 musicians: Monty on vibraphone and vocals, Phil Morrison on bass, Vinnie Johnson on drums, and a brass section with three saxophonists, two trumpeters and a trombonist. Footage exists of this line-up on the show and can be viewed on YouTube.

Soon after, Hoagy Jr. and The Stark Reality collaborated on composing and recording music for On Being Black, the first television drama series to portray life in America from a black perspective. They worked on the fly and virtually for nothing, using members’ apartments to record the music for the show.

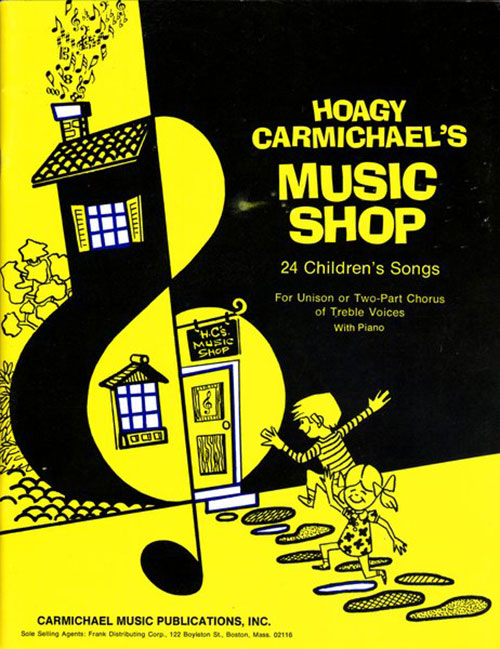

Never one to miss an opportunity to promote his father’s music, Hoagy Jr.’s next venture for WGBH, Hoagy Carmichael’s Music Shop was to give Dad a starring role — playing himself. Junior envisioned using songs from the 1958 children’s album Hoagy Carmichael’s Havin’ A Party for an educational children’s programme.

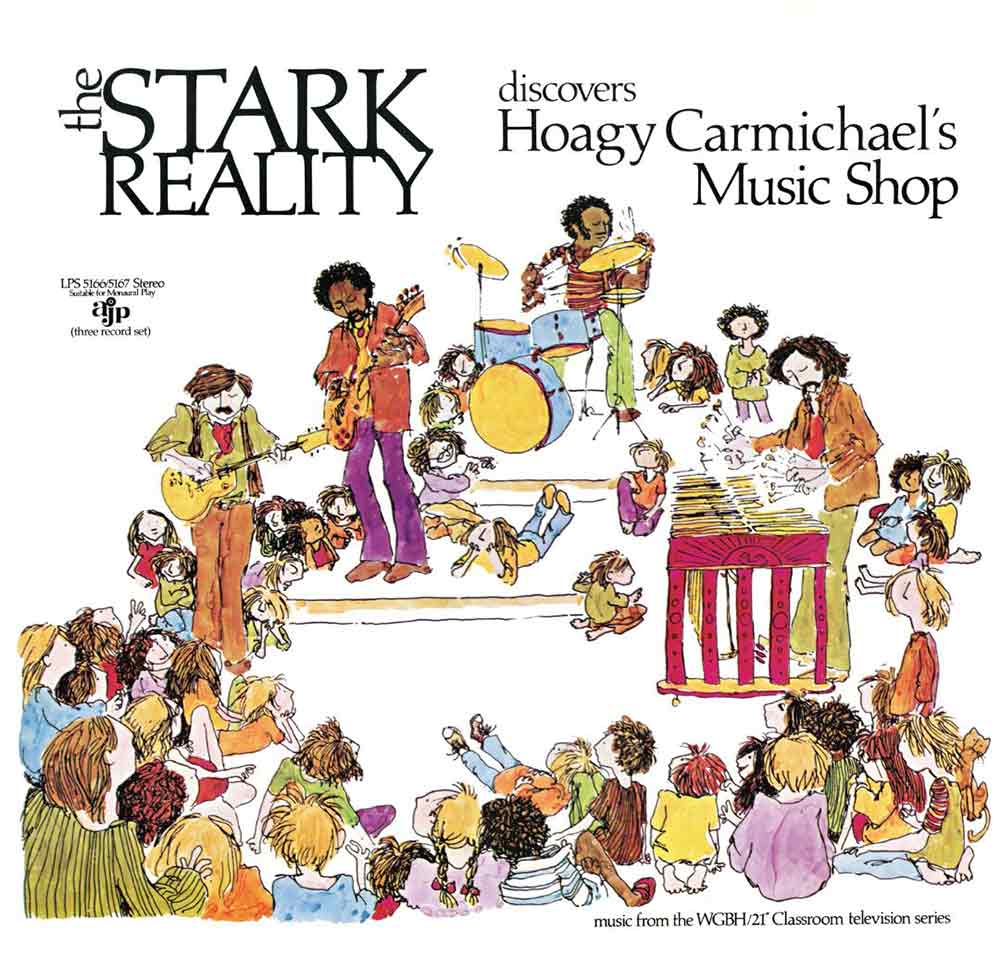

The LP’s concept had been Hoagy Sr. hosting a soiree for neighbourhood brats and regaling them with his more kiddie-centric ditties, such as ‘Rocket Ship’, ‘Merry Go Round’, ‘Sing Me A Riddle’ and ‘Grandfather Clock’. The TV version would add ‘modern pop’ renditions that would play over educational cartoon sequences, thus appealing to a broader audience. The Stark Reality was the obvious choice. Plus, they were cheap.

By this time, Monty Stark had reduced the band to a core line-up, retaining one of the saxophone players Carl Atkins, bassist Phil Morrison, drummer Vinnie Johnson, and recruiting a guitarist, fellow Caucasian and Berklee graduate, John Abercrombie. This version of the band recorded an album’s worth of demos that eventually saw the light of day in 2003 with the 1969 album.

The demos impressed jazz pianist Ahmad Jamal enough to sign the group to his short-lived AJP label, funding the Hoagy Carmichael recordings for an intended album release. Monty Stark went full-steam ahead “re-harmonising the living daylights” out of the songbook, coming up with a startling and unique take on these once child-friendly tunes.

Recording took place in April 1970 using a Scully 8-track stereo recorder and a homemade mixing desk. The personnel were minus Carl Atkins, who had left to found his own group the New Music Ensemble. They worked very quickly — the backing tracks, vocals and final mix completed in just three days. Most of the finished tracks were first takes and represent the only time the group ever played these songs.

The result of these sessions, The Stark Reality…Discovers the Hoagy Carmichael Music Shop is, without doubt, one of the strangest records of the 1970s.

Interviewed in 2003, Monty Stark said the intention was to play “beautiful melodies with an ugly sound… these were screaming times, there was Nixon, the war, cities burning down… a whole lot was going on, there was a lot to scream about.”

Stark was in the habit of individually miking his vibes then running them through a series of fuzz tones and pedals, allowing him to change their sound radically. He went for the jugular on this album, hurtling headlong into the avant-garde by producing heavily distorted effects that often rendered the source unrecognisable.

With John Abercrombie’s searing, dissonant shards of fuzz-tone and wah-wah drenched electric guitar; Phil Morrison’s supple, meandering basslines; and Vinnie Johnson’s accomplished jazz drumming, the Stark Reality conjured up a lurching, queasy, sometimes unsettling, often hypnotic, mood.

It is hard to imagine anything much further from the concept of children’s music and is undoubtedly many light-years from the 1950s schmaltz of the originals. Rumour has it that a cabal of sociopathic babysitters would play the album to disturb the minds of their young charges. Bed-wetting ensued; parents flummoxed. Or so I would like to believe. That said, I can imagine some kids enjoying the more anarchic moments; they occasionally remind me of the old Roobarb and Custard theme tune.

Hoagy Carmichael’s original lyric and melody would typically account for a short section of each completed track. 10 of the 17 recordings clocked in at over 6 minutes long, allowing the players to stretch and entwine, mostly going off on tangents completely unrelated to the core material. Not that their noodlings were entirely free form; each arrangement was finely structured with in-built room for manoeuvre. The programme would use only the vocal passages, so they were free to do whatever they wished for the rest of the recording. On ‘Rocket Ship’, Phil Morrison’s bassline was a Morse Code message sending peace and love.

Before I was aware that Monty Stark had sung all the vocals (“overdubbed four times” according to Hoagy Jr.), I thought the singer was black. It sounds like the black rhythm section of Phil and Vinnie is at least part of the vocal multi-tracking, especially when compared to older recordings that Monty sang alone. He is much less off-key here in any case!

Somehow the children’s lyrics make the songs more sinister. And does Monty really trill “Charles Manson” during ‘Junkman’s Song’? Twice? Sure sounds like it! Manson was awaiting trial for the Tate and La Bianca murders in April 1970. Perhaps he was alluding to Manson’s song ‘Garbage Truck’ (released the previous month on the cash-in album Lie: The Love and Terror Cult), but who knows?

Hoagy Jr. wrote to his father on May 11th, 1970, enclosing tapes of the finished record. Hoagy Sr. recalled his reaction in the double LP’s liner notes which are worth repeating here in their entirety:

A strange thing happened recently when my piano playing son Randy and I were on our way through a couple of scotch and sodas. A late afternoon delivery, and there I stood with all the tapes of the pre-recorded music for my children’s songs TV series.

“By the Stark Reality, it says here.”

“Who’s the Stark Reality?” asked Randy.

“Some group your brother Hoagy Jr. has been touting”, I said wearily.

But how to play them? Oh yes, that big tape recorder a college chum had given me for Christmas. A measly gift, and I had almost forgotten about it.

Luckily, Randy knew how to use it and out rolled some of the damnedest music either of us had ever heard. This is children’s music!? OK, Sera Sera – and Randy and I poured one quickie after another as we sat there losing our middle-class minds.

“Weird, man.”

“Stark mad.”

Monty’s voice? Somewhere between the filings on the edge of a pie pan and the singing of a guru during one of his most exalted moments.

I tell you that Monty is something else.

Despite his seeming reservations, Carmichael appreciated the musicianship and interpretive skill of the young band, even going so far as doing some writing with Monty and inviting them to accompany him on The David Frost Show. Astonishingly, they performed their lone single from the album, ‘Junkman’s Song’, somehow getting away with the Manson namecheck on national TV.

The Hoagy Carmichael Music Shop TV series was a modest success, and the Stark Reality received some local radio airplay. They played some club gigs in nearby Cambridge, Massachusetts, but they were under-publicised, resulting in more bodies on stage than punters in the audience. Ahmad Jamal secured them a week’s residency at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco with similar results, followed by a successful gig at Los Angeles’ Troubadour Club. Sadly, work dried up after this, and the group folded.

The vinyl-only album soon disappeared following the demise of AJP in 1970 and remained out of print until its 2003 re-release on Now-Again Records. In the meantime, its rarity value and reputation sky-rocketed, partly due to sampling by hip hop artists like Black Eyed Peas, Large Professor, J-Live and Madlib. As of writing, original copies of the 1970 vinyl double album are selling on Discogs.com for over £1,000 in less than mint condition.

The demise of The Stark Reality was a real shame and loss to 1970s music. Their album is a genuine lost classic, by turns joyful, humorous, intense, anxious, psychedelic and subversive.

Leigh Bushell

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress