What is an Offbeat film?

David Kerekes: What is an Offbeat film?

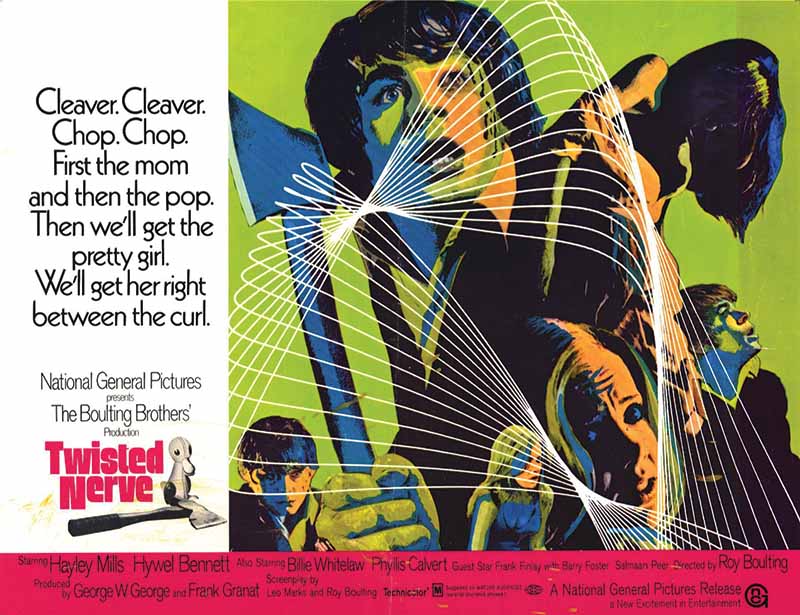

Julian Upton: Objectively, the term ‘offbeat’ can cover a lot of things, but for me the Offbeat project started as a tribute to a number of British directors who never became ‘names’—and certainly were never auteurs—but who regularly delivered good, solid films that were rarely hits but often had an enduring oddness or uniqueness to them. Directors like Roy Ward Baker, Val Guest, Cliff Owen (whose Offbeat [1961] provided our title), Michael Apted, Douglas Hickox, Vernon Sewell, Claude Whatham, Quentin Lawrence, Alfred Shaughnessy, Sydney Hayers, David Greene, John Krish, etc. We can add the early work of Michael Winner to that group. Their careers span the cheap but lively British B-movies of the late ’50s and early ’60s, through Hollywood-backed British fare of the 1960s, to the highlights of the much depleted populist British cinema of the 1970s and cover a range of exciting genres: crime, horror, sci-fi, comedy, melodrama, even the western!

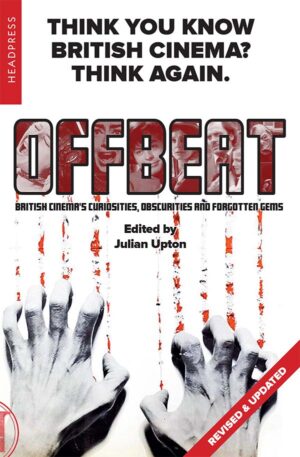

But the Offbeat project grew from there — especially as other writers came on board — and has come to include everything from ‘guilty pleasures’ to ultra-obscure films to some fairly big-budget fare. The main thing was keeping the focus on that mid-1950s-to-early-1980s boundary, which was a very productive time for British genre cinema despite the sporadic economic crises.

What inspired this revised and updated edition?

As more and more obscure and forgotten films continued to reach DVD, Blu-ray, streaming services and sites like YouTube, it was clear that the original Offbeat had only scratched the surface. We might also say that about this revised edition (and some probably will). But the book is subjective and selective; where I guess we could cover 500 films from the 1955–85 period, we’re focusing on at about 150 now. That allows for each reviewer to spend a bit of time revisiting their favourites or expounding their theories of offbeat British cinema in general, with room for the kind of individuality you wouldn’t necessarily get in a tome with much broader coverage. The essays are also important, and there are five new essays to add to the ten in the original. So there was definitely more to say ten years on. There is still more to say. I also wanted to remove some of my more embarrassing comments from the first edition.

What are the themes that run through Brit movies covered in the book (how might they differ from, say, US films of that same era)?

In the ubiquitous British crime thriller of the 1960s and ’70s, for example, I’d say the themes were very similar to the films coming from the US: honour among thieves, the ‘reality’ of a life of crime, the interchangeability of the cop and crook mentality, etc. It’s just that the British examples can either be more parochial and ‘quaint’ or, at the other extreme, in cases like Sitting Target and The Squeeze, more gritty and ugly and almost utterly resistant to glamourisation.

I think British horror and sci-fi films held their own with those from the US until films like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and, certainly, The Exorcist (1973) took US horror in a slicker and more powerfully visceral direction, leaving the British studios standing. Then Star Wars (1977) shifted the SF genre from that great dystopian era towards a multi-million-dollar industry seemingly intent on mass infantilisation, which is where we still are today.

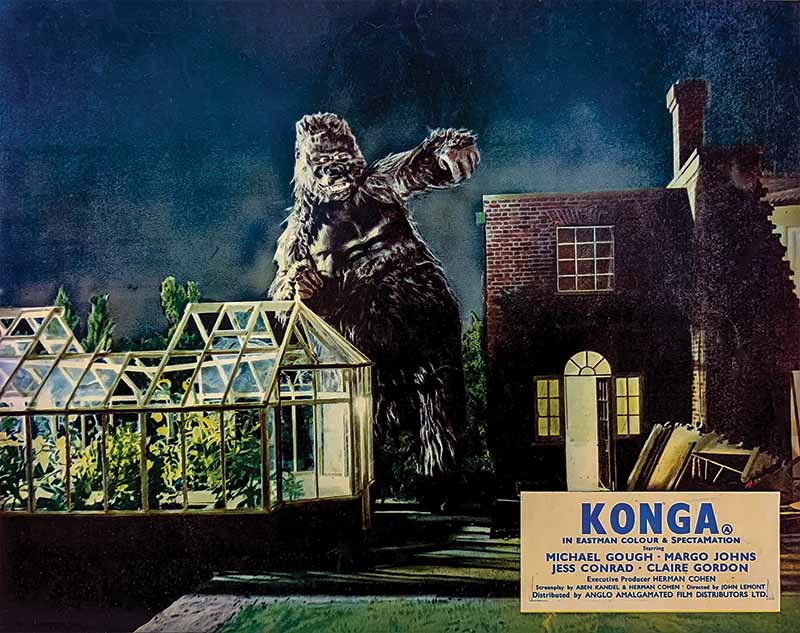

Hammer’s horror films, of course, indulged in Britain’s Gothic heritage, but I was always more fond of the contemporary-set horror and psychological thriller, and in that respect, the British films of the mid-fifties to the early-seventies were very much like their US counterparts. There were mad scientists, mutant monsters, Psycho imitators, Guignolesque chamber pieces, Satanists, sacrifices, cannibals, zombies. Britain also put out some creepy offbeat films with an unnerving power not necessarily found in US horror of the time: Never Take Sweets from a Stranger (1960), Night of the Eagle (1962), The Haunting (1963). The Hammer sci-fis and horrors of the 1950s still retain their uniquely English appeal and the Amicus portmanteau films have their quirky moments, but as I mention, with a lot of British genre films, it’s not so much how they differ from US fare but how much they were trying to do the same thing.

Five outstanding offbeat films?

That is a difficult question, but I suppose, for me, films that still stand out for me ten years after the first edition of the book are Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure (1959), Cash On Demand (1961), The Impersonator (1961) and The Squeeze (1977).

Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure shows that British cinema could make the type of exotic, rip-roaring Boy’s Own adventure of the type we usually expected from Hollywood — and could make it without stepping foot out of Britain (stock footage notwithstanding), with (mainly) British actors and on a very low budget.

Cash On Demand and The Impersonator are exemplars of that unassuming, black-and-white, low-key crime thriller of the early 1960s — the type you may have caught on TV on a rainy afternoon in the early 1980s — that nevertheless remain superior to much of the big budget fare of the time.

The Squeeze, as I’ve said to anyone who’ll listen, is perhaps the best British crime film of the seventies—and yes, I know the competition. It’s uncompromising, adult, squalid and brutal but with first-class acting and production—and yet it’s still barely remembered or discussed.

From the revised edition I think I’d add Frenzy (1972), which maybe shouldn’t really be in the book at all, being a major Hitchcock production. But it’s such a strange and perverse film — with Hitchcock so seemingly revived by his temporary move back to Britain that he felt free to push his capacity for permissive nastiness while stubbornly dismissing any concessions to contemporary London ‘realism’ — that it really occupies something of a class of its own.

-

Offbeat (Revised & Updated)

British Cinema’s Curiosities, Obscurities and Forgotten Gems

£11.99 – £37.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageThink you know British cinema? Think again.

- Interviews

- 1970s, Alfred Hitchcock, Alfred Shaughnessy, Cash On Demand, Claude Whatham, Cliff Owen, David Greene, David Kerekes, Douglas Hickox, John Krish, Julian Upton, Michael Apted, Never Take Sweets from a Stranger, Night of the Eagle, Offbeat, Quentin Lawrence, Roy Ward Baker, Sitting Target, Star Wars, Sydney Hayers, Tarzan’s Greatest Adventure, The Haunting, The Impersonator, The Squeeze, Vernon Sewell

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress