Figures in the Landscape: Rituals, Wilderness, and Canadian Cinema

Wilderness is not as straightforward as it seems. Though ostensibly a noun, the word ‘wilderness’ almost acts as an adjective; environmental historian Roderick Nash notes that the ‘-ness’ suffix suggests some kind of quality. In Canada ‘wilderness’ is a recognised legal term: there, wilderness is consciously managed via a series of protected areas that account for over 12 million hectares of Canada’s land mass.

As much as it is celebrated, wilderness is also feared. The renowned Canadian novel Wacousta by John Richardson, published in 1832, encapsulated what many saw as a specifically Canadian experience of wilderness: isolation, vulnerability, and entrapment. Images of the hostile wilderness in Canadian culture range from the Franklin expedition of 1845-46, to the mysterious drowning of landscape painter Tom Thomson in 1917. There is a tension in these fictional and real-life narratives between a glorification of landscape and fear of the dangers it holds.

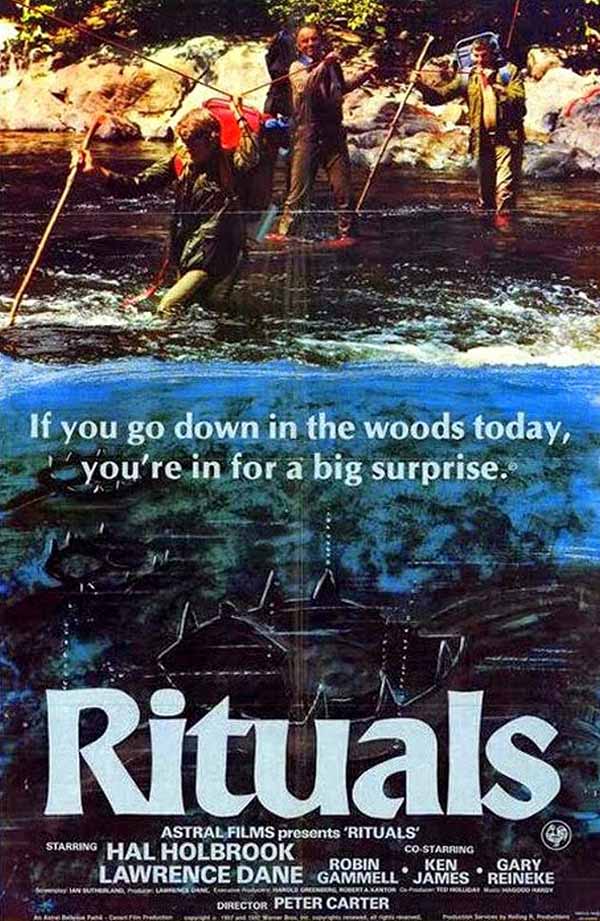

The landscape looms large in Canadian film too. In the tax shelter era of film production this was often a generic – not specifically Canadian – landscape. To attract audiences beyond Canada, American actors were brought in and Canadian locations downplayed or disguised. Peter Medak’s The Changeling (1980), for example, is largely filmed in British Columbia but presented as taking place in ‘upstate New York’ in the opening sequence. Such subterfuge had an economic rationale, as a way of drawing in wider audiences, but it often ended up glossing over markers of national and historical identity. It’s one of many forms of absence or deception that characterise Canadian films of this era, and Peter Carter’s Rituals (1977) is an interesting example.

In Rituals, the wilderness unleashes madness. Five city doctors go on their annual vacation, which takes them far away from their familiar urban lives. This modern idea of wilderness as a sublime, restorative, and transformative experience owes a great deal to the Romantic writings of Henry David Thoreau, as well as early conservationists like John Muir. The ability to escape the city was a major factor in national park development. In the 19th and early 20th centuries several national parks were created across the US and Canada, commodifying the landscape by making an explicit contrast between urban and rural: people could have their fix of the great outdoors before returning to their city desks on Monday morning.

The city-dwellers in Rituals, however, are ill-equipped for such an adventure. They lose their walking boots and have no spares. One of the most level-headed of the group descends into incoherent muttering. The threats that the wilderness poses are physical and mental, and the film’s tagline plays up this descent into primitivism: ‘In a world suddenly turned savage, the answers have become – brutally simple!’ By the end of Rituals, only one of the group is still standing. We last see him, exhausted, in the middle of an empty road with no guarantee that he will be saved.

From their inception, national parks were presented as preserving wilderness ‘for the people’. For the national park pioneers, though, wilderness depended not only on vast spaces, but also the absence of people. Indigenous residents were often evicted or barred from the spaces that they called home, including Yellowstone in America in 1872 and Rocky Mountain in Canada in 1885. In Rituals, the wilderness facilitates contact with the historical: the trek constitutes something of a journey backward in time, away from the modern world. Yet the men do not encounter the historical residents that one might expect. Instead, it’s revealed that they are being stalked through the forest by a deranged ex-serviceman who lives in the forest, hermit-like, re-living his traumatic memories of war.

The men’s trek in Rituals takes place in a forest basin known as ‘the cauldron of the moon’, named after an Indian legend about the moon touching the earth. The references to Indian myth contrast with the absence of any indigenous people themselves. The landscape in Rituals is empty, the deranged ex-serviceman is an anomaly; wilderness is defined by the absence of people. The one sign of ‘civilization’ the men find – a dam – has been abandoned. In erasing the indigenous figure from the landscape, the wilderness in Rituals is a place where one doesn’t encounter Others, but instead re-establishes contact with oneself. This is perhaps a more ‘primitive’ self, as we see the men dance and chant in a faux ritualistic way around their campfire.

The creation of wilderness in Canada, as depicted in Rituals, constitutes a re-drawing of the landscape as a place of escape for city-dwellers, glossing over the experiences of those who previously lived there. Perhaps this is because the historical experiences of indigenous people in this landscape have themselves been subject to significant manipulation and erasure. The establishment of Rocky Mountain Park in 1885, billed by the Canadian government as a way of protecting bison, was partly informed by vague eyewitness accounts that appealed to stereotypical notions of indigenous ‘destructiveness’. It was claimed that bison numbers were dwindling due to Indian blood-lust, and indigenous groups were promptly banned from hunting in the park. Similar ideas would resurface in the 1950s in response to the ‘caribou crisis’, when it was assumed that the decline in caribou numbers in the Northwest Territories was due to wanton slaughter by indigenous hunters.

The environmental and conservationist movements of the 1970s were alert to the colonialist attitudes that underlay earlier conservation movements. The ‘70s saw the establishment of three ‘national park reserves’ in Canada, a response to the land claims movement of the ‘60s and ‘70s. These reserves recognised the land claims of indigenous peoples for the first time, allowing for traditional hunting, fishing, and spiritual practices. From 1972, all new national parks had to be ‘reserves’, recognising that the state could not simply lay claim to the land.

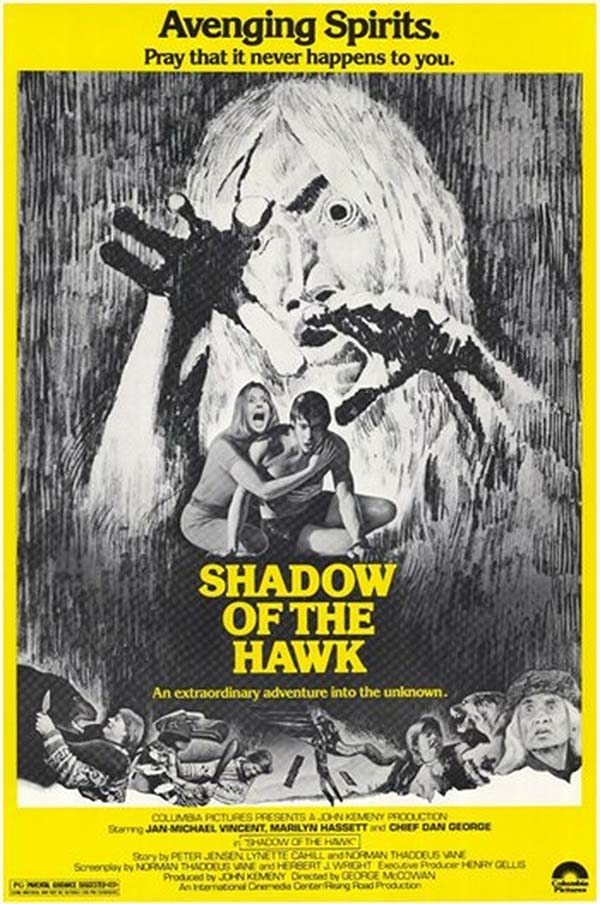

Where does this leave the wilderness in Canadian film, then? Rituals (and films set in similar locations like 1976’s Shadow of the Hawk) highlight how the Canadian wilderness may be ‘a geography of exclusion’ despite its apparent expansiveness and openness. The forest wilderness of Rituals nods to the past presence of an Indian population, but also shows the space to be inhospitable for city professionals. The missing ‘Canadian-ness’ of many films of the tax shelter era is twofold, then: the absence of recognisable Canadian landscapes was a marketing ploy, but the absence of credible, non-stereotyped, indigenous Canadian characters was also a reflection of longer historical practices of erasure. In place of the indigenous figure in the landscape, in many films of the era the wilderness itself becomes the central character.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress