When Folk Got Its Funk On

What Folk Is

The British folk revival in the 1950s emerged on the heels of skiffle and rock and roll. It existed in hundreds of clubs around the country, rooms above pubs, with some musicians going on to play to large audiences at rallies for causes such as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. ‘Folk singers, with few exceptions, did not belong to the establishment. They stuck to their ideals,’ says JP Bean in Singing from the Floor.[1]

Yet, folk music still holds a negative connotation, a finger in the ear, a chunky cardigan and all that. The stigma is not entirely unwarranted. According to Dave Swarbrick, a lot of the players on the folk scene ‘back then were a bit boring. It was about wanting to keep the music in a museum.’[2]

A shift took place in the 1960s, when, for some years, folk got its funk on.

What This Record Is

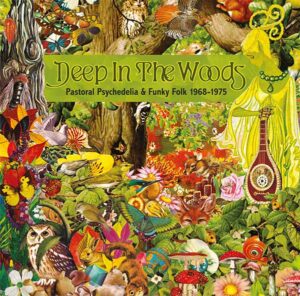

Deep in the Woods: Pastoral Psychedelia & Funk Folk 1968–1975 follows the pattern of other folk collections from Cherry Red: Dust on the Nettles, Sumer is Icumen In, and Before the Day is Done. It comprises three CDs of music by artists from the UK and Ireland, plus an informative booklet. The earlier volumes covered pagan folk, underground folk, and folk released on Heritage Records, while the theme here is a looser orbit. Deep in the Woods is what curator Richard Norris in his sleeve notes describes as ‘back-to-the-land meets LSD folk flavours’. This is my understanding: in the psychedelic sixties folk artists sonically amplified the oral storytelling tradition while evoking the ‘self’ through experimentation and inventive new studio techniques.

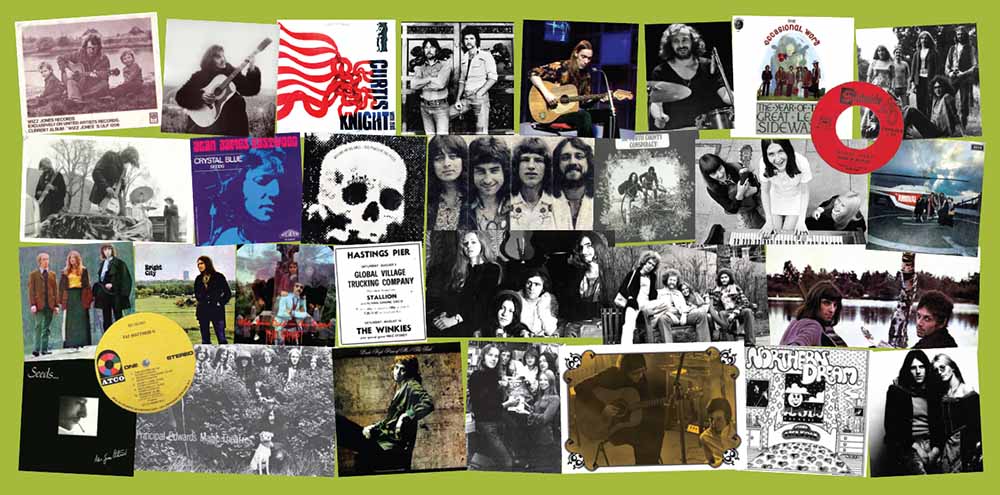

The inclusion of a track by The Deviants should give you some idea of the unorthodox selection criteria, although Bun, the track in question, is an elegiac instrumental and not out of place next to big-hitters like Trees, Mellow Candle, Wizz Jones, et al. There are others. Mike Hurst’s ‘Face from the Past’ features swirling Hammond and beefy horns, closer to Brian Auger than Ralph McTell, while ‘The Evil Venus Tree’ by The Occasional Word is dark psych pretending to be nice. The Occasional Word released one album on John Peel’s Dandelion label, and Peel would consider it fair to say that one or all members of the band may have been institutionalised at some point. Elsewhere, ‘Magician In The Mountain’ is not typical of the material on Sunforest’s Decca album, but something impressed Stanley Kubrick enough to include two Sunforest tracks on the soundtrack to A Clockwork Orange. Christine Harwood’s ‘Crying To Be Heard’ has a late-night funk-soul-jazz vibe that wouldn’t be out of place in Godspell or Hair. God rock is evidently a bigger influence on the era than it at first appears: Yvonne Elliman, another artist on Deep in the Woods, represented by the track ‘Hawaii’, would later play Mary Magdalene in Jesus Christ Superstar and have a hit with ‘I Don’t Know How To Love Him’. (Godfolk anyone?)

Tracks like these push the notion of the pastoral to its borders, but Norris makes a good argument for the collection. Folk in the high sixties had a crossover appeal and for a time was both counterculture and mainstream, as evidenced by the popularity of Donovan and The Incredible String Band. The key to success was swing, but swing in folk, argues Norris, posed a challenge:

‘Although some great drummers from the jazz, R&B and beat lineage also played in folk rock groups, they had their work cut out to make this stolid singalong anything resembling a loose groove.’

Not everything in the collection hits the mark. ‘The Death Of Don Quixote’ by Principal Edwards Magic Theatre plods while it swings. Another Dandelion signing, this lot were more performance troupe than a band but theirs is the longest track on the compilation and not much fun, despite the following spoken word interlude:

“When are they coming, Auntie Vera?”

“Shaddap, ya bastard. Watch the road.”

Norris says of invention:

‘The downside to this continual wave of ideas was a tendency towards novelty. The desire for the new and the now appeared to override almost every other impulse.’

The track is a clapped-out Hillman Imp painted with dayglo colours. Not everyone with an acoustic guitar is cut out to be a protest singer, and yet this collection encapsulates an era of music hitherto unrecognised prior to one’s arrival. This puts me in mind of Graeme, a good friend with whom I share a lot in common but for this: He has no interest in Argentinian psychedelic music and I could never understand his preference for compilation albums over ‘regular’ albums. He once burned me a CDr of artists who had all performed songs about apes at some point in their careers. Encountering a well-curated collection such as his ape-odyssey and this one, Deep in the Woods, makes me think that Graeme may have a point. I cannot picture The Deviants performing Bun in a smoky folk club in a room above a pub and yet I’d pay good money to see it.

For all its sidesteps and missteps the ‘creepiness’ manifest in the pastoral is evident throughout Deep in the Woods, despite its eclectic selection process, a grove like some audio chimera pitched too high for the human ear. I wonder whether the woods ever truly come to light without the discordant soundtrack? This collection is a fine companion to the other folk collections noted above, another fresh discourse with the ancient paths, surrounding the woods with the fabric of its own creation.

[1] JP Bean, Singing from the Floor: A History of British Folk Clubs (London: Faber & Faber, 2014), p.xiv

[2] ibid, p.215

- Music

- 1970s, Brian Auger, Cherry Red, CND, Dave Swarbrick, David Kerekes, Deep in the Woods, Donovan, Gathering of the Tribe, Godspell, Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar, John Peel, Mellow Candle, Mick Farren, Mike Hurst, Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, Ralph McTell, review, Richard Norris, Singing from the Floor, Stanley Kubrick, The Deviants, The Incredible String Band, Trees, Wizz Jones

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress