Books of the future: RedBlackInfinite and The Anything Box

ALEXANDER KATTKE’S REDBLACKINFINITE (2022) is, the blurb proclaims, ‘a work of atrocity and horror’. It wears its influences on its sleeve with quotations and references throughout: Burroughs, De Sade, and obsessions of the 1990s underground from JonBenét Ramsey to the Unabomber. Sotos-esque in its intensely personal and unflinching journey into the inner recesses of the mind, it’s often cringe-inducing. ‘YOU DON’T WANT TO BE INSIDE MY MIND’, Kattke writes, where squish films, mass suicides, and torture porn jostle for attention:

In a factory, a bound couple kiss in their final moments, a gigantic knife twice the size of their bodies impales both of them in an instant where they bleed to death. There is an assembly line of elderly people utilizing the cadavers of infants to build new machinery.

What is most interesting about RedBlackInfinite to me, though, is its sci-fi sensibility. The sections dealing with violent post-apocalyptic worlds are reminiscent of mid 20th-century offerings like J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World (1962) or Pat Frank’s Alas, Babylon (1959). Primitive horrors are set loose upon Earth. Demonic riders cavort on horseback. Dead bodies are used to fertilise crops. The occasional bit of surreal dark humour is a welcome touch:

We have developed techniques to bring people back from the dead utilizing the work that they’ve left behind … The subject selected in my division is Albert Einstein. We have scanned all of his materials and finished the reconstruction. When our Albert Einstein first spoke, it was a rambling speech that made no sense even to our best therapists. We monitored him and noticed traits not realized in his works such as a cannibalism fetish. He also groped a female assistant feeding him where he had to be restrained before he could do worse to her. Before we exterminated our test subject, he was raving about building nuclear bombs for World War 3, World War 4, and so on. We recreated the experiment and saw the same results each time.

In another segment, the works of Nietzsche are imagined as being repackaged for a juvenile audience:

I take on the bold task of reinterpreting Nietzsche in the form of children’s books. I will be the next Heidegger. I dedicate an entire book to the idea of Eternal Recurrence with a happy child being informed by a laughing dragon. The book sells moderately but children that have read the book have been reported with severe depression.

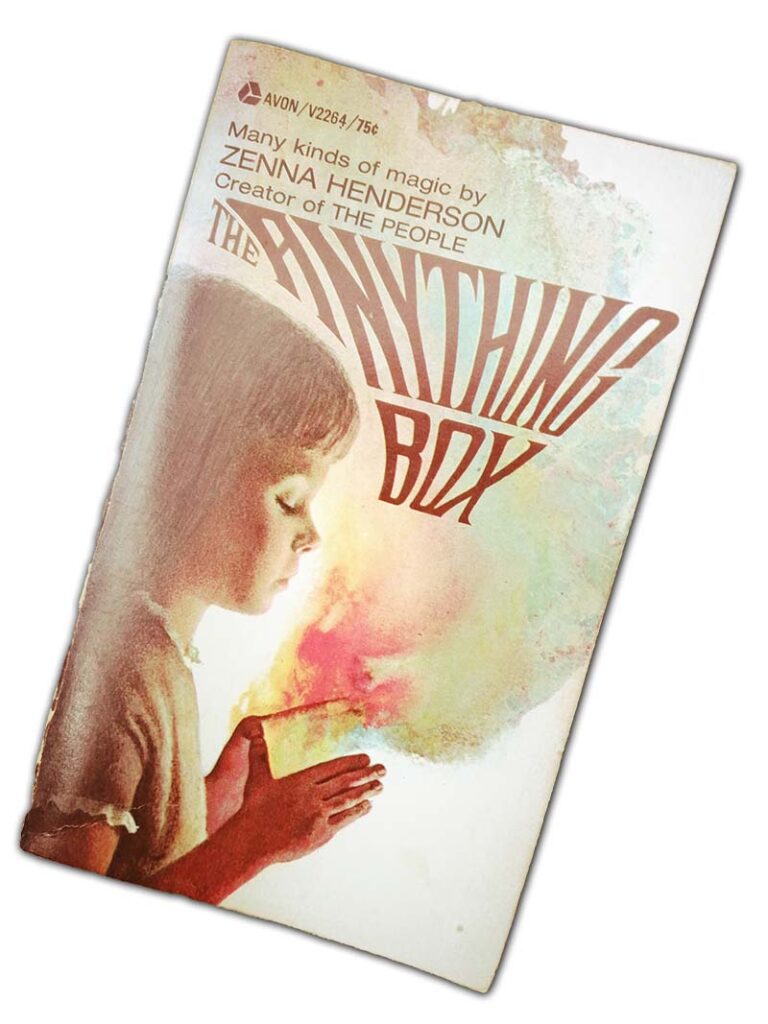

It’s simultaneously fractured and unrelenting (intentionally so), something to be read in small doses. And so alongside RedBlackInfinite I was reading Zenna Henderson’s The Anything Box, a collection of short sci-fi stories published in the 1950s and early sixties. Henderson, a schoolteacher from Arizona, is perhaps best known for her ‘People’ series, in which a humanoid alien race encounter fear and suspicion on Earth. Henderson’s work typified what Brian Aldiss and David Wingrove termed the ‘American Post-Technology Pastoral’. This was a branch of sci-fi that was ‘traditional, comforting, and deeply humanistic’, an approach that many sci-fi readers will associate with the work of Wisconsin-born Clifford Simak. Shying away from modern urban environments, Simak’s stories often took place in rural areas, where ordinary people – farmers, teachers, veterans – underwent extraordinary experiences involving aliens and windows into hidden worlds.

Like Simak, Henderson’s characters are down-to-earth and empathetic, easily accepting difference and strangeness. In ‘Subcommittee’ (1962), for example, a young boy and his mother befriend an alien mother and son. The group prove to be insightful and diplomatic enough to avert a full-scale world war, using their new friendships as a basis for intervening in government-level negotiations about how to deal with the ‘alien’ invasion. In the endearing yet distinctly unsettling ‘Stevie and the Dark’ (1952), a young boy tries in vain to contain The Dark that lives in a hole in a sandbank where he likes to play:

The Dark twisted itself into a thing so awful looking that Stevie’s stomach got sick and he wanted to upchuck. … The Dark screamed so hard that Stevie screamed, too, and ran home to Mommy and was very sick.

Reading Henderson’s stories alongside Kattke’s book was a pretty stark contrast. Although RedBlackInfinite isn’t billed as sci-fi (indeed, I’d struggle to categorise it at all), some of its most arresting segments fit into the sci-fi bracket. There is none of Henderson’s reassuring voice here, however. There are no saviours or supporters in Kattke’s world; we are all lost in the void of our own obsessions and predilections, however warped they may be. RedBlackInfinite feels even more resonant, more disturbing, because so much of it now seems possible. Many of the AI-oriented themes of RedBlackInfinite – digital immortality and VR simulations of the dead, for instance – seem less fantastical by the day. Case in point: Korean company Deepbrain now offers the Re;memory service, which allows customers to create an avatar of themselves to be visited by family and friends after their death.

‘In the future there are no more stories to tell’, Kattke writes. But perhaps, in the future, what will be most shocking will be those stories that return to the homely sci-fi worlds of Simak and Henderson – where the horrors are otherworldly rather than man-made.

- Reviews: Books

- Alas, Alexander Kattke, Babylon, Brian Aldiss, Clifford Simak, David Wingrove, Deepbrain, J.G. Ballard, Jennifer Wallis, JonBenét Ramsey, Marquis De Sade, Nietzsche, Pat Frank, Peter Sotos, RedBlackInfinite, sci fi, The Anything Box, The Drowned World, Unabomber, William Burroughs, Zenna Henderson

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress