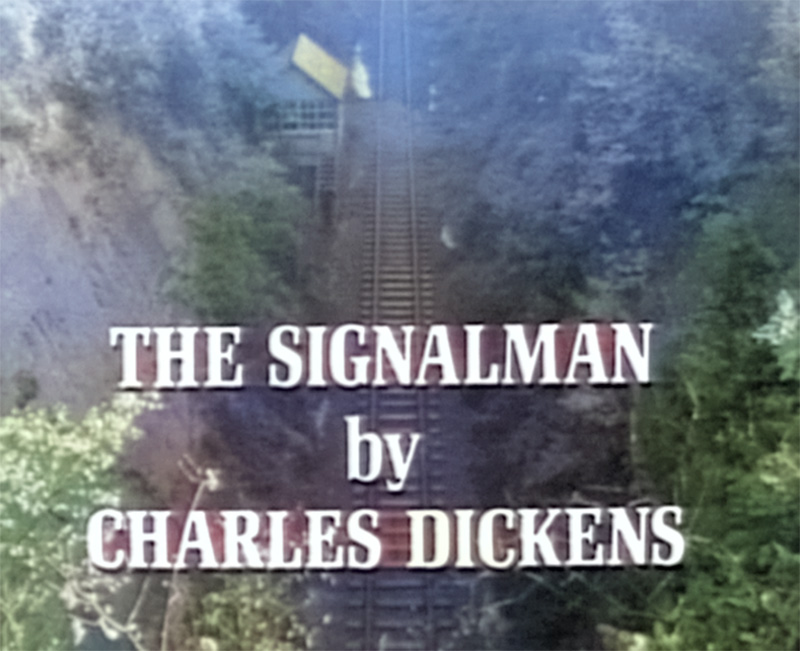

A Ghost Story For Christmas — The Signalman

The Signalman by Charles Dickens

A television version by Andrew Davies

Denholm Elliott (The Signalman)

Bernard Lloyd (The Traveller)

Jessup (The Engine Drive)

Carina Wyeth (The Bride)

Production Assistant Vee Openshaw-Taylor, Makeup Toni Chapman, Costumes Christine Rawlins, Music Stephen Deutsch, Sound Recordist Colin March, Dubbing Mixer Brian Watkins, Film Editor Peter Evans, Designer Don Taylor, Cameraman David Whitson

39 minutes

Producer Rosemary Hill

Director Gordon Clark

Broadcast

BBC1 10:40pm–11:20pm, Wednesday December 22, 1976

Repeated

Wednesday May 25, 1977

Saturday December 25, 1982

Saturday December 21, 1991

Tuesday December 2, 1997

Thursday December 3, 1998

Monday October 23, 2000

Tuesday June 4, 2002

And several more times on BBC Four since December 2007

The Signalman is a standalone drama produced by the BBC for its late-night festive strand, A Ghost Story for Christmas. The original 1970s run of eight programmes was largely based on the supernatural writings of M R James, one of the exceptions being The Signalman, adapted from a short story by Charles Dickens.

This review originally appeared in a slightly different form in Creeping Flesh: The Horror Fantasy Film Book vol 1 (Headpress, 2003).

The images used to illustrate the article are, for posterity, the ones that accompanied its original publication in 2003. The BFI had just begun to release BBC archive material and The Signalman, alongside A Warning to the Curious, was the first of the Ghost Stories to appear in any official capacity for home entertainment. Alas, the article was already written and the images — grabbed off a third- or fourth-generation VHS copy — ready for print in Creeping Flesh in grainy newsprint black-and white. Thanks to state-of-the-art computer technology, these very images have been colourized for a modern audience…

The Signalman has been released several times since, and this month marks its Blu-ray debut in the BFI’s sterling Ghost Stories for Christmas two-volume collection. The set brings together all eight of the original episodes, Jonathan Miller’s Whistle and I’ll Come to You, a precursor of the series, and a multitude of extras. These modest little dramas never looked so good, certainly not when they originally aired, and not when fans were writing about them in the pages of Creeping Flesh, a publication that existed as a vehicle for what was considered, at the time, obscure, forgotten or ignored British telefantasy; almost every review therein concluded with the statement: ‘Not presently available in any format.’

Times change. Much of the material in Creeping Flesh will appear again in some guise — on this site, for instance. It was Phil Tonge who inspired the original Creeping Flesh and made it possible, being one of the archival scientists talking about this stuff when few were, and collating videotapes, carrying the baton for a revival to happen.

Note that this should stand as archival material. I have resisted the temptation to fiddle with it too much. Also note that more informed material now exists concerning The Signalman and Ghost Stories for Christmas. Jon Dear is the authority on such matters: he provides the commentary on the BFI Blu-ray box sets and is the author of a book devoted to the subject, No Diggin’ Here, coming from Headpress in 2025.

- Contains spoilers

Synopsis

A man strolling across fields follows the sound of a passing steam train. He ends up on an embankment, overlooking a rail track and isolated signal box.

“Helloa!” he calls to a signalman, standing by the rail track. “Below there!”

The signalman, watching a red danger-light at the mouth of a tunnel, appears startled — fearful — of the cry.

The man calls again and makes his way down the embankment.

“You look at me as if you have some dread of me,” he tells the signalman. “I am simply a man.”

At first a little hostile, the signalman warms to the stranger and invites him to the signal box for a hot drink and to share the fire. When he becomes distracted, the traveller asks, “Is everything as it should be?”

“What brought you here?” responds the signalman.

“I was drawn here,” replies the traveller.

The signalman rounds out the evening with gruesome details pertaining to what he calls the worse kind of rail accident: the catastrophe of the tunnel accident.

The traveller arranges to visit again the following day and, at the request of the signalman, agrees not to call out in the manner he did earlier. He returns to his lodgings, a room at an inn, and that night peers from his window into the darkness, listening to the sound of a passing train. His sleep is uneasy: a dream about a tunnel collision and the signalman’s request that he doesn’t call out.

The following evening, the traveller meets again with the signalman, who reveals that what troubles him is a spectral figure that sometimes stands at the mouth of the tunnel. The figure covers his face with one hand and waves slowly with the other, as if in warning. The same cry always heralds his appearance: “Helloa! Below there!”

The first sighting was about a year ago, and within six hours “a memorable accident on this line occurred” — a collision in the tunnel.

The traveller, a man of some learning, dismisses the spectre as a trick of the mind, a deception. “We are men of good sense —” he begins to say. But the signalman isn’t finished. Six or seven months later, the figure appeared again at the mouth of the tunnel, beneath the red danger-light. The signalman implored: “Where is the danger? What can I do?!”

The spectre dropped the arm from its face to reveal a mask frozen in an empty scream. Then the train emerged from the tunnel, and a bride was thrown from it to her death.

He concludes the story with the revelation that the spectre last showed itself a week ago. “I have no rest or peace for it,” he says, knowing that this third appearance foreshadows yet another calamity and that he remains powerless to do anything about it.

“Take comfort in the discharge of your duties,” consoles the traveller. “You cannot be to blame.”

The signalman is consoled by the traveller’s words. They arrange another meeting, and the traveller heads to the inn and again falls into a troubled sleep. He wakes with a start to find the door to his room ajar.

Out walking the next day, the traveller stops in his tracks on hearing an ethereal whistle. It’s clearly the whistle the signalman has spoken of; a communication from the grave. He bolts for the rail track. Meanwhile, having heard the familiar refrain of “Helloa! Below there!” the signalman stands at the mouth of the tunnel, transfixed by the spectral figure, and fails to heed the oncoming train. The traveller arrives in time to see the signalman hit by the train and killed.

A shocked train driver laments how he tried to call out but the signalman didn’t seem to notice. His words to the signalman: “Helloa! Below there!” as he waved his hand in warning. “Look out! Look out!”

The traveller is overcome — by realisation, by shock, by fear — and his face becomes a mask, frozen in an empty scream.

Critique

The Signalman is a claustrophobic work so isolated, so estranged, that it might well be taking place in a vacuum. It’s a two-man piece, with the closing credits referring to Denholm Elliott simply as the “signalman” and Bernard Lloyd as the “traveller”. But the play itself dispenses with even these base references, and nowhere in the production is anybody referred to by any name at all.

The setting is perfect: a signal box locked on each side by a steep wall embankment, which has only one hazardous means of negotiation, up or down. The rail tracks that cut through the landscape disappear into a black tunnel at one end, while in the opposite direction they appear to slip into infinity. Both directions are foreboding and neither suggests the slightest hint of escape for the men caught between the two.

The claustrophobia and ambiguity take on a surreal quality. The inn where the traveller is boarding (described only as “a fair walk” away) is shrouded in perpetual fog. There are no guests or anyone else that the traveller encounters, and even the name of the place is veiled by swirling mists.

The only other people in the whole production are perfunctory characters, who — save for the engine driver at the end — say not a word. They behave as though they belong in a completely different time zone. Their actions (if they have any; most are static) are laboured. After the bride is thrown from the train, one of the mourners at the trackside clutches his face in such a precise way that the viewer supposes the action must convey some significance. Well, it does and doesn’t — it really depends on how deeply you wish to interpret The Signalman’s odd denouement.

The framing of The Signalman is carefully considered, with the camera lingering a couple of seconds more than it should on many scenes, compounding the surreal quality. A particularly masterful shot features the signalman walking from the tunnel after the first accident, standing in a near perfectly symmetrical landscape, smoke billowing out behind him.

Although the part of the traveller appears at first to be ‘straight man’ to the signalman’s ramblings, i.e. the voice of reason, his exact role becomes less obvious over time. When he first introduces himself, he empathises with the signalman’s solitude, stating, cryptically, that he himself is a man used to confinement, but now is free. Nothing in this play has any true history or value; everything is in a limbo of the here and now. Or purgatory. Could it be that the traveller is a channel for the supernatural — as the signalman seems to think at one point, given his first words of greeting? And what of the creaking open door that he discovers on waking at the inn — what is implied in that? A visitation? It isn’t clear. But the ending, in which the traveller’s face takes on the attitude of the spectre, appears to signify that the traveller himself is the unwitting harbinger of death. Indeed, in his description of the accident, the engine driver uses the same curious words uttered by the traveller days earlier: “Helloa! Below there!” All told, not likely the thing one would shout in desperation to clear the path of a fast-approaching train.

There is never any doubt the supernatural is playing a part in the whole play, which makes the traveller’s attempts at rationalising what he considers a deception of the mind a little unnecessary. The signalman is aware that he has too much time on his hands; there is so little to do, he acknowledges, and yet so much depends on him. At the same time, he wonders what might be the purpose of trying to build knowledge (in the signalman’s case, through books on mathematics) if he has no outlet for that knowledge? Here The Signalman skips around some deep philosophical concepts, and again it isn’t clear what role any of it plays in the grand scheme of things. The spectre is clearly not a deception of a bored mind, neither is it a reaction to scientific conceit — a direction in which we appear headed at one moment.

The dramatization is close to Dickens’ short story, ‘The Signal-Man,’ first published at Christmastime 1866 as part of a series of railway-themed stories under the collective title, Mugby Junction. The significant difference is that Gordon Clark’s dramatization plays up the supernatural element. The traveller in Dickens’ original story doesn’t witness the death of the signalman, only the aftermath, neither does he suffer bad dreams or mysterious goings-on at the inn. There is only a perfunctory reference to the traveller’s lodging, and most of the time is spent with the two men talking. Tonally this changes the story, makes the ‘reality’ of a spectral presence ambiguous and puts the onus on the signalman as a potentially unreliable narrator.

The Signalman — Gordon Clark’s dramatization — has the markings of an allegorical tale (the “signalman”! the “traveller”!), but then nothing is quite what it seems and there is no allegory, no pearl of wisdom upon which the viewer might ruminate.

The whole episode works with its restrictive budget remarkably well. The spectral face is simple and enormously effective. Points of action, such as the bride falling to her death and the signalman’s own demise, are insinuated rather than shown. The only time the play does overreach itself is the catastrophic accident in the tunnel, which is simply a series of train wreck noises over a blank screen. (I’m sure I used to have that BBC sound effects record!) This scene brings an unintentional element of humour.

Outside of natural noises, the soundtrack uses no music or incidental sound beyond the ghostly warning, which takes the form of a subtle hum. Again, effective. Elliott and Lloyd play their parts admirably, with Elliott bringing his customary weight and dignity to his role (there is a wonderful moment when he might be cribbing his lines from a note on the palm of his hand!).

Of all the BBC Ghost Stories, this is the only one I have any recollection of having sat through on its original airing in the seventies. It impressed me a lot, and when I came to see it a second time, many years later, courtesy of a BFI DVD release, it impressed me over again. I was surprised at just how vivid and accurate my memories of it had been. But then, every scene is precious, without a wasted moment in the whole production.

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress