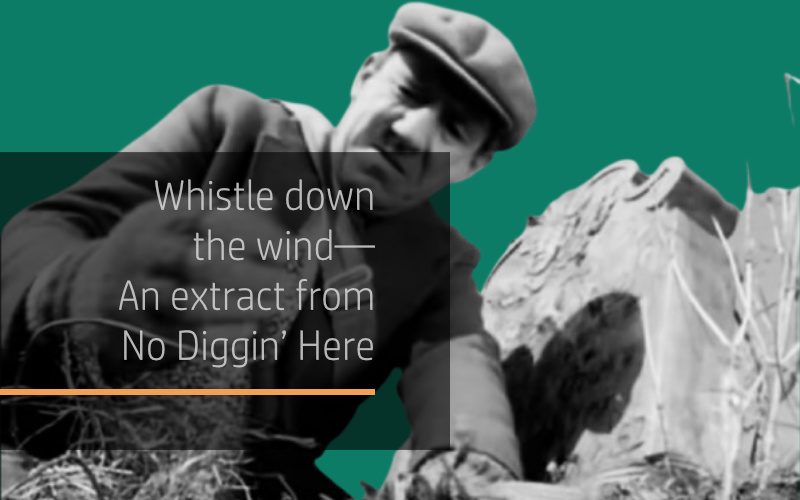

Whistle Down The Wind — An Extract From No Diggin’ Here

The film you are about to see is a tale of the supernatural. Strangely enough it was written by man who only wrote ghost stories as a side-line. M.R. James is one of England’s most distinguished medievalists and a great expert on classical Archology and the early history of the Bible. He was, in turn Provost of King’s College Cambridge. He is known to the general public, however, for a very special brand of horrifying ghost stories all of which conjure up beasts of darkness and the vague irresistible forces of the unseen world. Perhaps the grizzliest of these stories is the one called “Whistle and I’ll Come to You”.

It is a story of solitude and terror, but above all, it has a moral too. It hints at the dangers of interlectual (sic) pride, and shows how a man’s reason can be overthrown when he fails to acknowledge those forces inside himself which he simple cannot understand.

First draft of the introduction to Whistle and I’ll Come to You by Jonathan Miller, dictated over the telephone by his secretary.

12:45, 1 March 1968

The Last Grave is cut off from human visitation by a barrier. The nearby interpretation board identifies JACOB FORSTER “who departed this life March 12th 1796 Aged 38 Years”. Of course, the barrier isn’t really there to protect the grave from human vandals, it’s to stop people going over the cliff (a warning to the curious if you will), and Jacob is the wrong side of the fence. Either way it’s too late for him. Jacob’s bones may have been laid at All Saints church but that will not be their final resting place.

Dunwich is on the Suffolk coast, and the history of the major shipping port that is now no more than a quiet village, thanks the severe effects of coastal erosion over the last thousand years, is well documented. Our interests here are a little more focussed. Where I stand on the crumbling bank that was once the foundation of a small city nearly two miles to the east is where Jonathan Miller and Dick Bush filmed Michael Hordern finding a whistle by a grave in December 1967. It’s not Dunwich’s first brush with ghost stories. E.F. Benson references the town and its fate in The Dust-Cloud first published in the Pall Mall Magazine in January 1906. At the time of writing the whole of All Saints had yet to disappear into the North Sea but it was known that it would, as it was known that the odd bone and other human remains would occasionally ‘weather’ down on to the beach. This is a location made to show the beauty in the macabre and the eerie. The landscape of Dunwich is generous in giving up its secrets.

In Chapter VI of his seminal text of psychogeography, The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald discusses how the people of Dunwich kept what little remains of the place alive by building inland, to the west. “The east” says Sebald “stands for lost causes.” Thinking also of the American settlers and the end of the Cold War. This part of the British coastline can certainly feel bleak and hopeless, the call of the omnipresent curlew is both mournful and lonely, and yet it’s just down the road from the extremely popular tourist town of Southwold. Home to the Adnams brewery and The Ship hotel, where the cast and crew of Miller’s groundbreaking interpretation of M.R. James’s Oh Whistle and I’ll Come To You, My Lad! were based[i].

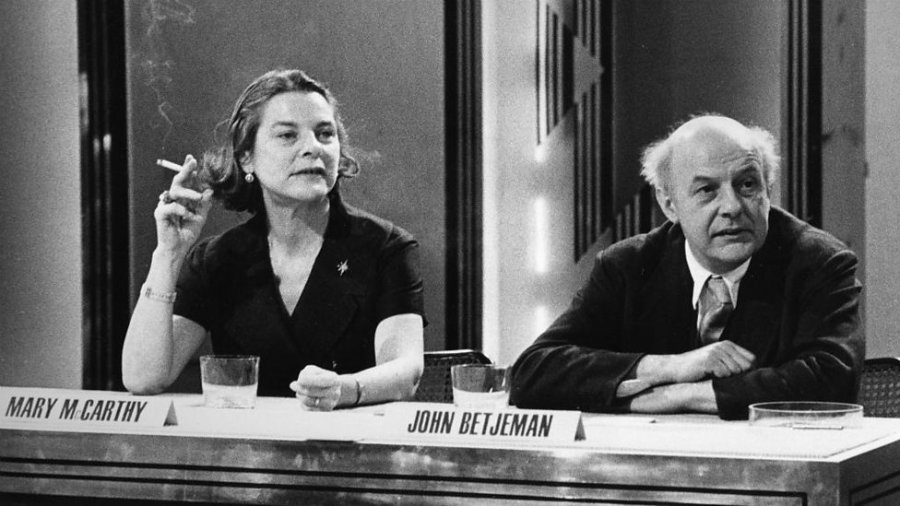

This 1968 film is of course, not a BBC Ghost Story for Christmas. It’s not even a ghost story for Christmas, being first broadcast on 7 May 1968. But this most famous episode of Omnibus, from its first series, sandwiched between a look at China and the Barbarians, and a biopic of Florentine sculptor Benvenuto Cellini (portrayed by future Ghost Story for Christmas alum Peter Vaughn) is undoubtedly the progenitor of the series, and the film’s success would aid Lawrence Gordon Clark in convincing Paul Fox to fund an adaptation of M.R. James’s The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. In any case Whistle… has been rather retconned into a ‘pilot’ for A Ghost Story for Christmas and is mentioned in the same breath and released in the same collections by the BFI on DVD and Blu Ray (I hear the commentary is *very* good). So while, as I have discussed, this is not the first M.R. James adaptation made for television. It’s not even the first M.R. James adaptation made for television that was broadcast in 1968. It is the beginning of a new way of looking at the work of M.R. James, and of how ghost stories are told, and it remains the go-to approach to this day. This journey can be traced to one man’s appearance on television: John Betjeman.

But before we get onto that, let us briefly turn to an earlier adaptation that WAS made for Christmas and so is a BBC ghost story for Christmas (although still not a BBC Ghost Story for Christmas).

Mollie Greenhalgh worked as a BBC radio announcer during the Second World War. The Radio Times listing from 28th September 1944 for the General Forces Programme informs us that she “introduces massed brass bands (conducted by Harry Mortimer) playing at the Town Hall, Huddersfleld.”[ii] This was part of Strike a Home Note, a series of regional transmission recorded for British service personnel abroad, made up of local bands, choirs and variety performers. After the end of the Second World War, Greenhalgh worked for the BBC script department, beginning in children’s programming. Her first broadcast script was The Trough of Bowland on 16th June 1946. She quickly graduated to adult drama and became one of the Home Service’s most prolific writers, proving herself as a skilled adaptor on series such as Lark Rise to Candleford, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, starring a young Prunella Scales, and the ubiquitous A Book at Bedtime. In 1961 she married fellow writer John Michael Drinkrow Hardwick who was best known for his Sherlock Holmes adaptations on The Light Programme.

I spoke to Sherlock Holmes adaptation expert Dr. Mark Jones about their early days of working together.

“They were staff writers at the BBC, in adjoining offices as I recall, before they became a couple. Michael had written a couple of radio adaptations in the ’50s which brought him to the attention of Adrian Conan Doyle (Sir Arthur’s youngest), who seems to have held them in esteem as he kept putting them forward for things. In 1962, they wrote The Sherlock Holmes Companion which sold out almost immediately and was proof of the burgeoning commercial appeal of Sherlock Holmes.”[iii]

In 1963 they began writing for Mystery Playhouse, adapting ghost stories from the likes of Eleanor Farjeon, E. Nesbitt and of course, M.R. James. Their first James tale was Martin’s Close, broadcast on 20th August 1963 (an appropriate date for a more summery tale) but producer Charles Lefeaux knew what would make the perfect story for Christmas Eve of that year. Oh, Whistle and I’ll Come To You was broadcast at 11:30, it’s write up in the Radio Times simply stated ‘Easy enough to whistle – but there’s no telling what will answer.’ The production featured many familiar names from the BBC Radio Repertory Company, including Hilda Kriseman, the superbly named Earle Grey, the slightly more awkwardly named Rolf Lefebvre and Sheila Grant. But most strikingly, four years before he crossed paths with Jonathan Miller, Lefeaux cast Michael Hordern as Prof. Parkin.

A recording of the play survives and what becomes immediately apparent is how different this is to Miller’s film both in terms of the overall production – this adaptation is told in flashback and is topped and tailed, as the original story is, with the scenes at Cambridge University – and in Hordern’s performance, which is comfortably within the expectations the listener would have from reading the original short story. Essentially this is a faithful adaptation and thus makes the contrast with Miller’s film all the greater.

Radio is of course a more straightforward medium for prose adaptation, narration is more easily integrated with speech, and this cosy, Christmas broadcast in the freezing winter of 1963 was perhaps not the place for experimentation. Nevertheless the concept of ghosts is introduced early and somewhat arbitrarily and it features a number of instances where characters rather obviously describe what they’re seeing (plus a rather weak Colonel Bogey joke). And having the apparition say “No, it’s me…hahahaha!” at the climax is more comical that frightening. In short nothing about this production will revolutionise the ghost story adaptation.

That’s where the likes of Omnibus come in, and the fact that Miller was watching the Robert Robinson fronted literary quiz show Take It or Leave It where poet laureate John Betjeman discussing M.R. James. And this gave Miller an idea…

“Film subjects usually occur to me without much warning. One evening last autumn I was watching John Betjeman on “Take It or Leave It”. He was talking about the ghost stories of M.R. James and I was reminded of the grisliest of them all – “Whistle and I’ll Come To You”. I knew that this would have to be my next film for the BBC.”[iv]

To be continued…

Notes

[i] The lighthouse at Southwold was also visited by director Paddy Russell in preparation for the Doctor Who serial Horror of Fang Rock (1977).

[ii] Radio Times Issue 1095, dated 24th September 1944.

[iii] In conversation with the author, 20 October 2024.

[iv] Radio Times Issue 2321, dated 4th May 1968.

- News and Book Excerpts

- 1970s, A Book At Bedtime, A Ghost Story For Christmas, Adrian Conan Doyle, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Benvenuto Cellini, Dunwich, E.F. Benson, Jacob Forster, John Betjeman, Jon Dear, Jonathan Miller, Lark Rise to Candleford, Lawrence Gordon Clark, M R James, Michael Hordern, Mystery Playhouse, No Diggin' Here, Oh Whistle and I’ll Come To You, Peter Vaughn, Prunella Scales, Sherlock Holmes, The Haunted Box, The Rings of Saturn, The Stalls of Barchester Cathedral, W.G. Sebald

Jon Dear

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress