Godsends and Bad Seeds: Evil Children and Child Deaths in Horror

AT OCTOBER’S Festival of Fantastic Films in Manchester, one of the films on offer to festival-goers was a rather unlikely one: 1980’s The Godsend. Directed by Gabrielle Beaumont, with a screenplay by Olaf Pooley, The Godsend was briefly introduced by I Spit On Your Celluloid author Heidi Honeycutt as part of a Headpress tie-in screening. Heidi described the film as a ‘sophisticated’ and ‘gut-wrenching’ example of the ‘tragedy porn’ genre.

It is, certainly, a distinctly unsettling film, and my mind has repeatedly wandered back to it since viewing it in October. There is no elaborate preamble, as we jump straight into the life and home of the Marlowe family. Parents Alan and Kate (Malcolm Stoddard and Cyd Hayman) live with their four children in a large rural house where, almost immediately, they receive a visit from The Stranger, played by Angela Pleasence (always somewhat unsettling in her own right, I find). Rather like the way a cat turns up at an unknown door just before giving birth to kittens, the white-robed Stranger delivers a baby daughter in the spare room before swiftly disappearing and leaving the Marlowes with an unexpected addition to the family. We jump from month to month as we see baby Bonnie grow into a quiet toddler with a shock of blonde hair (if one thing ruined The Godsend slightly for me, it was this rather obvious allusion to Village of the Damned that seemed somehow out of sync with the rest of the film).

The interesting thing about The Godsend, for me, was that it seemed that much of what happened may or may not have been the work of a homicidal child. Soon after Bonnie’s arrival, the Marlowes young baby dies in its cot. Although we are encouraged to believe that Bonnie caused this, we never witness her direct involvement in this or the other deaths in the film (though she most definitely does maliciously launch a playground swing at someone). The Godsend plays not only on the evil child trope, but also on genuine anxieties about child death in the period. The Godsend was made when fears of ‘cot death’ (now referred to as Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, or SIDS) were at their height. The period between the 1970s and early 1990s saw much debate about the condition, culminating in 1991’s Back to Sleep campaign which advised parents to place babies on their back, not front, when sleeping. (SIDS remains a somewhat mystifying condition, likely with multiple causes, as the label ‘SIDS’ simply refers to the context of death.) The death of one of the Marlowes’ sons, too, drowned in a pond, is more reminiscent of 1970s public information films than supernatural horror (one can almost hear Angela’s father’s doom-laden voice narrating the scene of ‘dark and lonely water’). No explanation is ever given for the appearance of Bonnie as the cuckoo in the nest, nor any resolution offered, even as we witness Pleasence’s character reappear at the end of the film, pregnant again and approaching another unsuspecting family in a park.

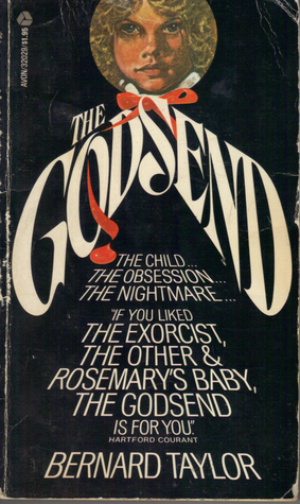

Perhaps this lack of clarity is why the film wasn’t particularly well received upon release. Although the 1976 book it is based on, by Bernard Taylor, is explicitly billed as horror (unsurprisingly so, in a decade that also gave us sinister child novels The Exorcist and The Other), the film version is less explicit. No doubt it disappointed some viewers who saw it as a double feature with the Klaus Kinski vehicle Schizoid. There is more than a little of Don’t Look Now about it, albeit without the Venetian splendour and visual flair of Roeg’s film – though there is some interesting use of B&W film. The bucolic English countryside seems desolate and threatening, only to be replaced – towards the end of the film – by an equally dangerous urban environment.

It is a film perhaps more in keeping with The Bad Seed (1956), based on the 1954 book by William March. The Bad Seed sees the nauseatingly sweet Rhoda Penmark (Patty McCormack) calculatingly dispatch whoever she feels has wronged her, or who has something she would like – pushing an old lady down the stairs to inherit a keepsake, and pitching a schoolmate into a fast-flowing river in her desire to possess a school medal. The Bad Seed is a wonderfully uneasy film, in large part due to the raw emotion of the actors. When Mrs Daigle (Eileen Heckart) – descending into alcoholism after the death of her young son – breaks down in the Penmarks’ home, her anguished distress is discomfiting to watch. Just as central to the film as the sinister actions of the pigtailed Rhoda, are the appalled realisations of her mother and the gradual mental breakdown of the other characters. In both The Bad Seed and The Godsend, we are shocked by how easily death may arrive in the ordinary homes of ordinary middle-class families, and how quickly the domestic idyll can be shattered.

Playground danger in The Godsend; and Rhoda and her mother in The Bad Seed.

Like The Bad Seed, The Godsend seems to me less about ‘evil children’ than about human grief and the turbulence of family relationships. Although at face value they are a wonderfully happy couple, Alan Marlowe demands that his wife Kate make her choice between Bonnie and their biological daughter Lucy, and throughout the film we are reminded of Kate’s frustration at having to make all-or-nothing decisions, like abandoning her career to play the ideal homemaker. The matter-of-fact depiction of child death verges on the documentary rather than the fantastic, appealing to those real-life worries that were so present in public discourse of the 1970s (SIDS) as well as the everyday anxieties of parents of young children (falling into ponds, or out of windows). It is, as Heidi Honeycutt says, a sophisticated film that works on multiple levels, encouraging the viewer to draw their own conclusions.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress