Visiting the Serial Killer World Tour: London

A time of Visitors

AT THE HOLBURNE MUSEUM in Bath recently, visiting an exhibition of art by Paula Rego and Francisco de Goya, I witnessed the anarchy of a high head count: the many visitors packed into the modest space travelled from one picture to the next in single file, a crawl dictated by the person in front. But some visitors manoeuvred recklessly, without patience, unwilling to oblige the natural flow of traffic. The lady behind me craned a long neck out of turn to look at the very things I looked at, in this instance a drawing of a man hanged by the neck with his trousers fallen down (Goya, The Disasters of War, plate 36). On it went, the creeping head next to mine, imposing itself upon a nicely coloured grotesque, a print showing people dropping food into their mouths (Rego, Untitled (People Eating), 1993), at which point I left the line for another room.

Not like that in ‘Serial Killer World Tour’. The space for this particular exhibition, disused railway arches beneath Waterloo station, is bigger than the Holburne, and while it’s a more populist attraction and confrontational like Goya in his day, the threat of a rubbernecker bottleneck is halted somewhat by the timed admission.

Vault of Horrors

‘Debunk the mysteries behind the most twisted minds of the century with an exploration of serial killers’ lives from a scientific, historical and educational perspective.’ [1]

Serial Killer Exhibition website

The Vaults prides itself on being a ‘home for immersive theatre and alternative arts’, a maxim signalled by the dense graffiti along Leake Street, the tunnel in which the exhibition is located. Two guys dip into a canvas bag filled with spray cans, adding fresh decoration to one area of the wall. Further along is the entrance to the exhibition, a doorway that barely registers on the psychedelic landscape, save for a queue of people outside it.

The Serial Killer World Tour occupies a series of soberly lit rooms of various sizes containing the artefacts of serial killers — art, letters, clothing — plus graphic representations of crime scenes and the forensic science utilised in the hunt for these killers. ‘Manson, Bundy, Dahmer and more are waiting for you!’ goads the invitation on the official website. Material of this sort has been collated before in a variety of guises, although I haven’t encountered the like in a while and rarely in the UK on such a scale — Crime Through Time in Gloucester is a notable exception. Serial Killer World Tour is presented as an edifying experience but walking through its black-walled rooms you may soon see it more as a celebration, not so much a reflection on the human condition as it is a sideshow attraction populated with distorted little people standing tall. There was more of this kind of thing in the final years of the previous century, more sideshows, more crazy mirrors. Think in terms of Lustmord: The Writings and Artifacts of Murderers, a 1997 book that compiled the art and writing of killers without fanfare or apology. Or, before that, the unapologetic tone of certain zines. Murder Can Be Fun springs to mind (“Do you really want to hurt me?” sings the blurb on the cover of issue two, beneath a photo of Sylvia Likens.) In the Vaults beneath Waterloo lies a similarly discomforting aesthetic.

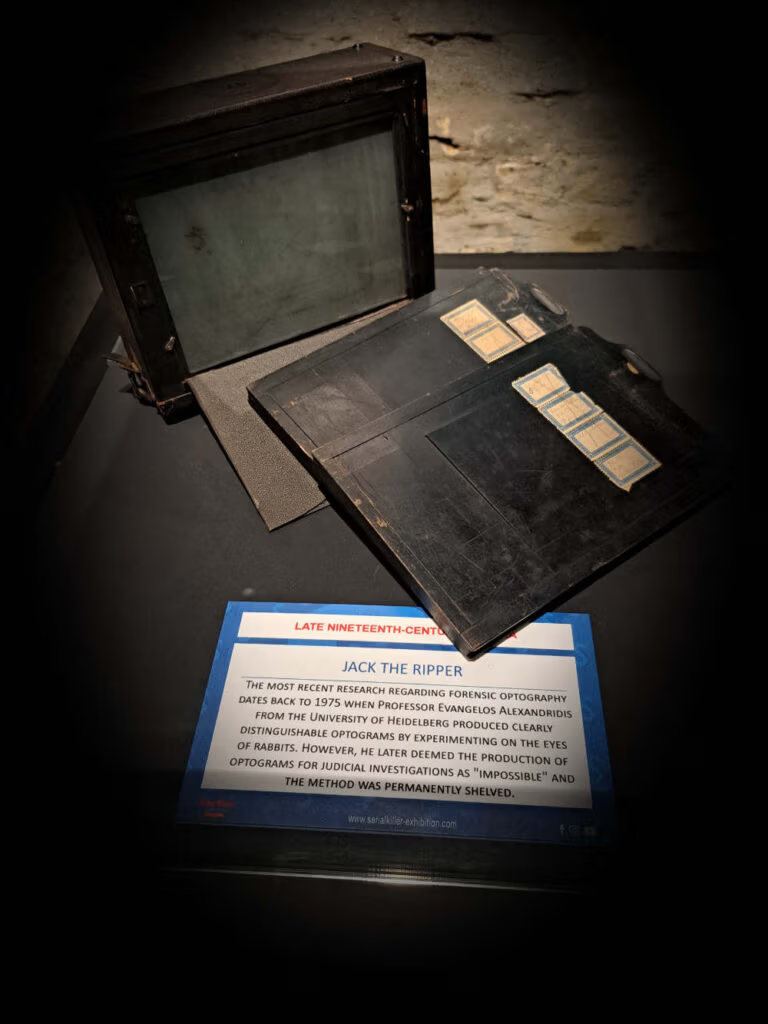

Jack the Ripper

A section devoted to the first modern serial killer opens the exhibition. A life size tableau shows Mary Jane Kelly, Jack the Ripper’s final victim, discovered in November 1888 in her rented room in the East End of London. Reconstructed from the police photograph is a scene so barbaric that it defies comprehension. Kelly is a savage primer and I wonder how many visitors, confronted with her mutilation, may not have ventured further.

Details pertinent to the Ripper case, and the cases to follow, are showcased in a variety of ways: exhibits under glass, life-size replicas of people and scenes, and charts, masses of charts, prompting one commentator to liken the exhibition to a PowerPoint presentation. The inclusion of a Gladstone medical bag conforms to the belief that the anonymous Jack was a surgeon, or wannabe surgeon. Jack’s era was one of burgeoning photography, the forensic pictures of his victims being the first of their kind, and this fact is contextualised in bullet-point notes. In the nineteenth century rose a theory that the eye might record a final image before death, thus the eyes of one Ripper victim were photographed on the pretext that the killer’s identity might be revealed. Optography is now a debunked science, but something in it I feel holds true. The world, according to F. Scott Fitzgerald, only exists in your eyes. Mine go awry shortly after this exhibition. It begins on the train journey home. In the morning, with my eyes turning to rust, Specsavers will refer me to the emergency eye hospital on a diagnosis blissfully ignorant to this parade of killers.

I leave this stage of the exhibition with the keen words of a fellow tourist ringing in my ears. In the chamber that contains Mary Jane Kelly, her poor body mashed into a totem of unbelievable horror, also sits a modest item of furniture. “This room wouldn’t have been like this in those days,” the visitor observes. “A chest of drawers would have been a luxury.”

Hunting Humans and the Decline of the English Murder

It’s unlikely that many people will wander into Serial Killer World Tour without some expectation of who and what to expect. But what might that be? The conventions of serial murder are broad enough to have thwarted any formal definition for years; even the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit, established in 1972 and having created the term ‘serial killer’ in the first place, were at pains to come up with a clear account. It wasn’t until 2005 — in a symposium titled Serial Murder: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives for Investigators — that the Bureau formally quantified what it had been studying all along:

Serial Murder: The unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s), in separate events.[2]

Author Michael Newton, in 1992, spoke of a changing face of modern homicide, ‘a new breed of “recreational killers” who slaughter their victims at random for the sheer sport of killing’.[3] Elliott Leyton, meanwhile, immersed in killers’ diaries, psychiatric interviews and statements for years, asked himself whether serial killers are insane. Published in 1989, Leyton’s book bears the same title as Newton’s — Hunting Humans — and his findings, if more pragmatic, are no less alarming. He sees their motives as so obvious

and their gratifications as so intense that I can only marvel at how few of them walk the streets of America. Nevertheless, their numbers do continue to grow at a disturbing rate…[4]

I toy with the collective noun for this modern phenomenon of serial killer but all the best ones are taken. A brace of serial killers. A siege of serial killers. A murder of serial killers. And how did we quantify this new breed and rising tide before we had a name for it? The weekly anthology magazine, Crimes and Punishment, published in the UK in the early 1970s, borrowed a theory from A. E. Van Vogt to describe those who kill without motive. Van Vogt, sci-fi author and unorthodox psychologist, while studying divorce cases reported in the press, noted that many husbands were inclined to make difficult or impossible demands on their wives and almost never admitted to being wrong. When pressed, such men flew into a violent rage and doing so they would derive satisfaction, that somehow they had been right all along. Van Vogt called this the “right man”. The author of the Crimes and Punishment article (likely Colin Wilson; none of the articles in Crimes and Punishment carry an author credit but Wilson is the series authority on ‘Crime and Society’ and this reads a lot like him) posits that the theory might also help to explain modern murder. Random killings are described as having become the most typical and frightening sort of murder, and to dismiss them as simply an act of resentment against society, as many presumably do, is next to meaningless. Thus the “right men” come into play.

George Orwell also speaks of the changing face of murder in his essay, ‘Decline of the English Murder.’ The British people love to read about murder but in 1946, when his essay was published, Orwell considered its perpetrators to be lacking.[5] He offers cases from ‘our great period in murder,’ roughly 1850 to 1923, whose reputations have stood the test of time (alas, Mrs Maybrick, I had to look you up) and compares them to the cleft chin murder of 1944. George Edward Heath, a man with a cleft chin, is one victim to this newer breed of killer, a high profile case in it’s day and an irrational one, without clear motive other than the two killers had an interest in American gangsters and pop culture. The ‘strong emotions’ prevalent in classic British murder cases, notes Orwell, are absent here.

I suppose Orwell might have said much the same of France, had he still lived in France and not moved to Wigan. France has its own golden era, La Belle Époque, and its people noted for crime passionel are twice as murderous as those living in England, according to author Rayner Heppenstall.[6]

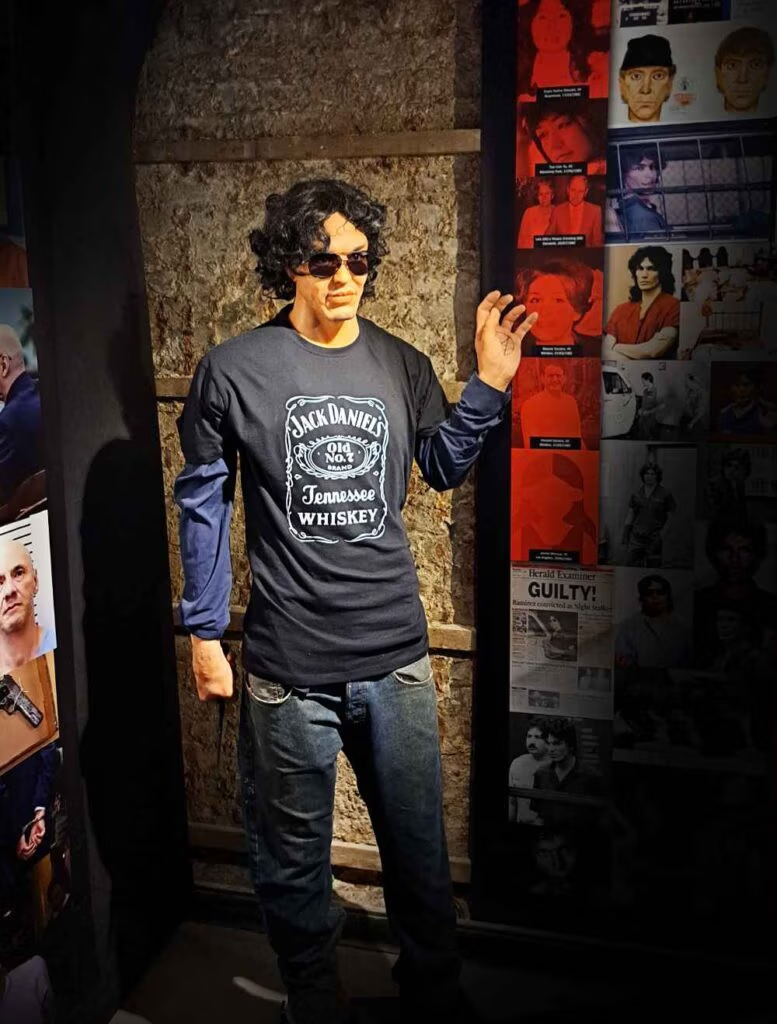

Pause a moment for Richard Ramirez. Ramirez, the so-called Night Stalker, is represented in one corner of the exhibition by an uncanny life-like dummy. Smirking behind sunglasses, dressed in Jack Daniels t-shirt and jeans, he displays the pentagram engraved on the palm of one hand. A visitor peering too closely at Ramirez, a lady with a frown, soon gets over the fact that Ramirez, the killer of at least thirteen women in Los Angeles in the 1980s, is much shorter than she imagined. Soon, she volunteers to her companion forensic details in the case, gleaned from a Netflix documentary that is evidently exciting to recall. The details are harrowing but in her skittish delivery they sound a little bit naughty and saucy, like a plot line in Emmerdale.

‘What the detective story is about is not murder but the restoration of order.’

P.D. James

Stephen Milligen, in his 2006 book, Better to Reign in Hell, determines that serial killers are a fabrication of the FBI and nothing more than a moral panic. Serial murder constituted an attack on American society, says Milligen. Compounded by the media and the political manipulation of Ronald Reagan and America’s New Right, the threat of serial murder instilled fear, serving to ‘legitimize and perpetuate the existing social order and to persuade individuals passively to accept the values of society’.[7]

On my way to Krispy Kreme in Waterloo station I pass WHSmith, where for sale is a special edition of the Daily Mirror which aggravates the idea of serial murder as a media construct. That’s not all. Crossing busy Addington Street, I stumble on another construct, Van Vogt’s “right man”, driving a white van. In fairness, the van need not be white, and the vehicle any type. But this motorist has been on the rise for years, driving with arrogance as if eager to be angry. Wanker! — he gestures from behind the wheel of his van and, having hurled his silent abuse toward me, safe at last on the other side, he drives off at speed, satisfied he was right all along.

Published to coincide with the Serial Killer exhibition but otherwise unrelated, the Daily Mirror special — Britain’s 1,000 Unsolved Murders — presents a timeline of unsolved British murder cases, beginning in 1938 and ending in 2022 (Jinming Zhang, forty-one, is stabbed to death following a suspected robbery in Digbeth). The introduction deals primarily with serial killers — two are said likely to be active in Britain at any given time. But, calling on expert opinion, the author of the piece, journalist Richard Ault, concedes that very few of the featured cases are likely the work of serial killers. [8]

The Cannibal Cookbook

True crime statistics for serial murder can never be fully accurate because killers for the most part like not to be caught. But serial killers are popular entertainment, as indeed are the people who hunt them down, an omniscience that creates the illusion of greater numbers. Think of the vogue for murder memorabilia; John Borowski made a documentary (and later a TV series) called Serial Killer Culture (2014), which shows collectors as a sometimes ghoulish and conflicted bunch, ransacking murder scenes for altogether unremarkable souvenirs. Other collectors acknowledge a purely fiscal interest, regularly corresponding with convicted felons to procure and sell their original art, and some talk ethics and speculate on why this fascination with damage in the first place.

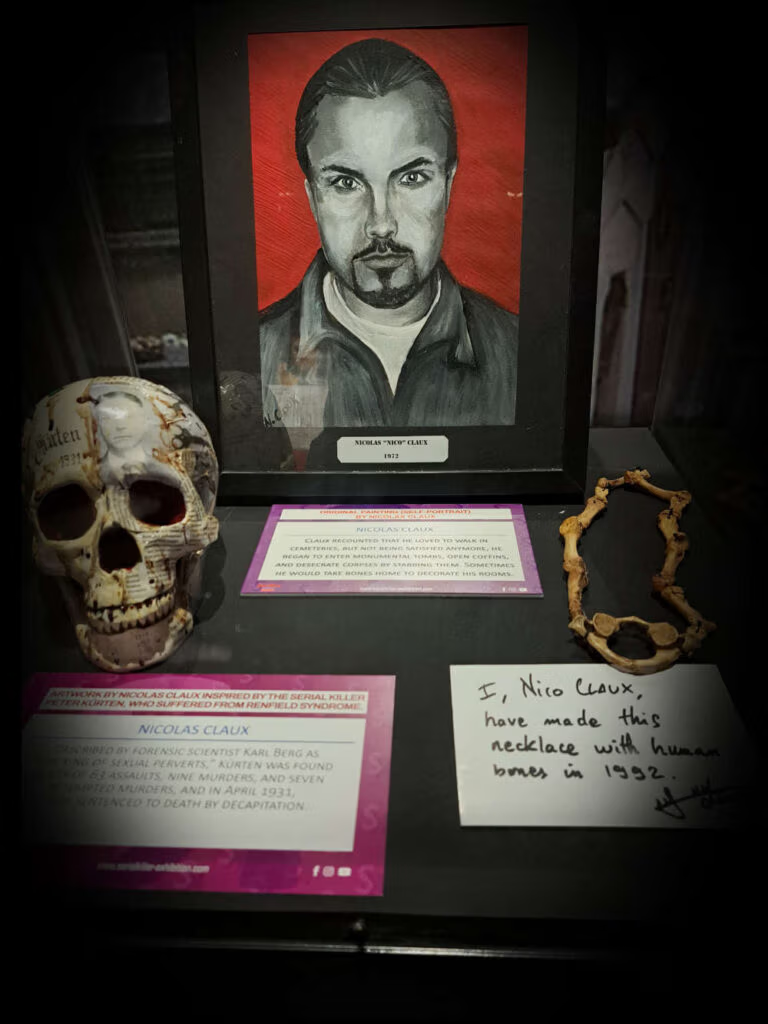

This exhibition clearly understands its market. I wonder who might be behind it, and where the exhibits have come from. The exhibition book — a stylish full colour paperback — identifies Italmostre, an Italian company specialising in the promotion of major events, including a similarly edgy sounding exhibition in Alessandria, Italy (Crimes Serial Murders Real Bodies). However, among the items displayed in London, one name crops up time and again in correspondence with other killers. Nicolas Claux derived pleasure from cannibalising and consuming the flesh of corpses while a mortuary attendant in a Parisian hospital. He was imprisoned in 2002 for the premeditated murder of Thierry Bissonnier, a man he had met online, and served four months of a seven year sentence. Given the boasts made by the twenty-two-year-old Claux — a cannibal, the desecrator of graves, that he stole and drank blood from the hospital — there was an attempt to link him to several unsolved murders in Paris.

The boasts continue in London. A cabinet displaying a Claux self-portrait also contains a necklace that Claux constructed from human bones in 1992 accompanied by a personal letter of verification. Later, in the gift shop, among the serial killer fridge magnets are postcards signed by Nico Claux (£7 each) and a variety of slim kill-themed books published by a company called Serial Pleasures. I pick up The Cannibal Cookbook and flip through it. There are a series of pencil drawings and not too many words but among them a question: Will eating human flesh will make you sick? Following this are tips on where to find human meat — morgues and funeral homes are the safest bet — and advice on how to cook and prepare it. Another section features recipes, offhandedly named after a noted killer or historic case of cannibalism. For instance, Dennis Nilsen’s Bacon-Cheese Dip … David Harker’s Macaroni and thighs salad … Fritz Haarmann’s shoulder spam … It’s a queasy read.

I don’t purchase The Cannibal Cookbook but I do the exhibition souvenir book, a purchase that entitles me to a free poster of Ted Bundy, whose smiling portrait bears the legend ‘Lady Killer’. I thank the member of staff serving me and ask where in the home one would ordinarily display a poster of Ted Bundy. It’s rolled up for convenience, with an elastic band. Then I ask:

“Is Nicolas Claux behind this exhibition?”

She replies, tentatively. “I think so, yes. He was here when it opened, signing autographs. I don’t know if he will be here again. Would you like a receipt?”

Signing autographs? Comments on the exhibition Facebook page are mixed. The prospect of meeting the Vampire of Paris — described by the organisors as ‘a reflective session’[9] — is evidently a thrill for some people. But for others a genuine murderer is unwelcome. I sympathise with the lady for whom an otherwise enjoyable visit is spoiled by Claux waiting near to the exit. She considers it unethical and in poor taste, which itself is interesting, as if a display of bad things can be in good taste but the arrival of a genuine murderer is altogether bad. Scratching my head I type ‘taste’ into Google and at the top of a long list is ‘taste’ in relation to cannibalism and human meat. Algorithm be damned, that’s not I want. So I type again, arriving now at a YouTube clip for Sabrina Carpenter, whose top forty-five song called Taste features in a music video I listen to on mute, that so happens to be a grand guignol gorefest not without charm.

Notes

[1] https://www.thevaults.london/serial-killer-the-exhibition

[2] https://www.fbi.gov/stats-services/publications/serial-murder#two

[3] Michael Newton, Hunting Humans: The Encyclopedia of Serial Killers Volume 1. New York: Avon, 1992 p.1

[4] Elliott Leyton, Hunting Humans: The Rise of the Modern Multiple Murderer. London: Penguin, 1989 p.12

[5] George Orwell, Decline of the English Murder, London: Penguin, 2009, p.15

[6] Rayner Heppenstall, quoted in J.H.H. Gaute and Robin Odell, Murder Whereabouts. London: The Leisure Circle Ltd, 1986, p.14

[7] Stephen Milligen, Better To Reign In Hell: Serial Killers, Media Panics and the FBI. London: Headpress, 2006. p.126

[8] Richard Ault, Britain’s 1,000 Unsolved Murders, a Daily Mirror undated but purchased November 2024. 64pp (p.2)

[9] Serial Killer The Exhibition Facebook post, September 18, 2024

The exhibition’s next stop is BERLIN at the end of August 2025.

- Event Report

- 1000 Unsolved Murders, A. E. Van Vogt, Better to Reign in Hell, Britain’s Charles Manson, Colin Wilson, Crime Through Time, Crimes and Punishment, Crimes Serial Murders Real Bodies, David Harker, David Kerekes, Decline of the English Murder, Dennis Nilsen, Elliott Leyton, F. Scott Fitzgerald, FBI, Francisco de Goya, Fritz Haarmann, George Edward Heath, George Orwell, Holburne Museum, Hunting Humans, J.H.H. Gaute, Jack the Ripper, Jeffrey Dahmer, Jinming Zhang, John Borowski, Lustmord: The Writings and Artifacts of Murderers, Mary Jane Kelly, Michael Newton, Murder Can Be Fun, Murder Whereabouts, Netflix, Nicolas Claux, Optography, Orbis Publishing, Paula Rego, Rayner Heppenstall, Richard Ramirez, Robin Odell, Ronald Reagan, Sabrina Carpenter, Serial Killer Culture, Serial Killer World Tour, serial killers, Serial Murder: Multi-Disciplinary Perspectives for Investigators, Stephen Milligen, Sylvia Likens, Ted Bundy, The Cannibal Cookbook, the Night Stalker, the Vampire of Paris, Thierry Bissonnier

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress