Singalongacharlie: The Music of Charles Manson

[su_quote cite=”Charles Manson”]If that judge asks for my life I’m going to give it to him…but first of all he is going to have to deal with my music[/su_quote]

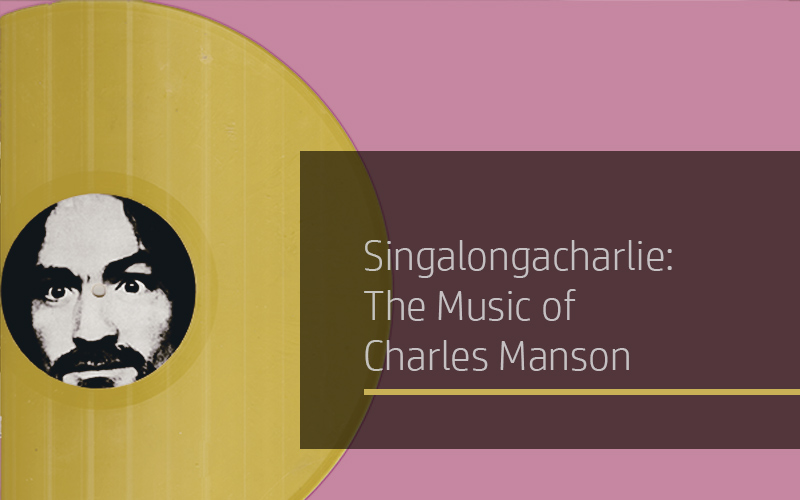

A photograph records a man, perhaps in his mid thirties, with shoulder length hair, parted in the centre, and a neatly trimmed goatee beard. The man’s wide-open eyes are fixed just off to the side and seem to convey a fierce mania. To some the picture is silly; to others it is a terrifying portrait of evil. This image of Charles Manson, the ultimate hippie leader with a difference, began as a police mug shot and then became the cover shot for Life magazine. While the story of his life and times is well known (the arrival of each Manson ‘anniversary’ is marked with feature films, documentaries, magazine articles and more interviews) those once close to Manson — chief prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, stars like Dennis Wilson, Sharon Tate, Doris Day — have come to be defined by their proximity to his potent presence. Manson = pure evil: Mike Tyson famously once stated: “Look, I’m a bad guy, but I’m not Charles Manson.” The advent of the internet has seen an explosion of Manson goods, trivia and opinion. The malevolence of Manson’s cult has entered cyberspace. Manson, because of the bizarre nature of the killings associated with him, now more than ever epitomises the notion of ‘apocalypse culture’.

A photograph records a man, perhaps in his mid thirties, with shoulder length hair, parted in the centre, and a neatly trimmed goatee beard. The man’s wide-open eyes are fixed just off to the side and seem to convey a fierce mania. To some the picture is silly; to others it is a terrifying portrait of evil. This image of Charles Manson, the ultimate hippie leader with a difference, began as a police mug shot and then became the cover shot for Life magazine. While the story of his life and times is well known (the arrival of each Manson ‘anniversary’ is marked with feature films, documentaries, magazine articles and more interviews) those once close to Manson — chief prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi, stars like Dennis Wilson, Sharon Tate, Doris Day — have come to be defined by their proximity to his potent presence. Manson = pure evil: Mike Tyson famously once stated: “Look, I’m a bad guy, but I’m not Charles Manson.” The advent of the internet has seen an explosion of Manson goods, trivia and opinion. The malevolence of Manson’s cult has entered cyberspace. Manson, because of the bizarre nature of the killings associated with him, now more than ever epitomises the notion of ‘apocalypse culture’.

Yet despite the ubiquity of the legend of Charles Manson, Manson’s recorded music remains somewhat indistinct. It’s easy to forget that the picture described above is also a record sleeve — of one of the most infamous records of all time. Despite the internet Manson’s music still contains an ‘underground’ vibe. While everyone knows of ‘Charles Manson’ few have actually listened to his recordings. Music is the glue that sticks Manson to his friends, his fellow travellers, his ‘Family’, his enemies. It is through music that Manson connected (via the group The Milky Way) with Bobby Beausoleil (composer of Kenneth Anger’s Lucifer Rising soundtrack and according to Truman Capote “the real mystery figure of the Charles Manson cult”). Also with the Beach Boys, Neil Young and the Beatles. You could argue that the Manson story (to quote Beausoleil) “is all music”. Those that speak of Manson do so not with words but, according to David Felton and David Dalton, in “noises, guttural sound effects, gasps, shrieks”. The musicality of such expressions mirrors the coyote yips and yells that Manson and his followers utilised for communication while awaiting trial for murder.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

It’s all music

Music is the principle reason for why Manson is still a figure of intrigue and obsession

One of Manson’s purest legacies is his audio recordings. Manson is described as a ‘man with a thousand faces’ and this is reflected in his music. The many studies of Manson’s crimes claim to pay due attention to his musical output. But all too often the writer is distracted back to the vivid and still shocking killings that belong to the Manson legend. Music is the principle reason for why Manson is still a figure of intrigue and obsession and maintains the countercultural credibility that other killers patently lack.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

Helter Skelter

Groups like the Rolling Stones packaged and resold violence and revolt in an immature and egotistical way

Manson’s association with the giants of rock music became a kind of creepy subconscious epitomising the time when rock met the counterculture, the moment when revolt rubbed shoulders with wealth. With the Beach Boys (through their drummer and hidden genius Dennis Wilson, who called Manson “the wizard”) this was a physical connection. With the Beatles it was psychic, imaginary. Manson deliberated over the Beatles’ eponymous 1968 LP (aka the ‘White Album’) with the studious devotion of a monk. It’s no surprise that he and his followers became obsessed with that record and that Beatles’ lyrics were repeated in Manson ‘sermons’ (“The glass onion is the door of water and the hole in the ocean is the pool in Death Valley”). Manson quoted The Ballad Of John And Yoko — identifying himself with the Christ figure in the song. The Manson reading of the ‘White Album’ was the first of many such fascinations with the record’s sound, image and content. Early Manson historians such as Bugliosi and Ed Sanders detected the eerie power of the record. Its minimalist blank white cover invites open interpretation, the kinds of experimental freethinking that the epoch — through mind-altering chemicals and radical head theories — invoked. The LP seems to speak to the future of rock music whilst detonating the idealism and egotism of the 1960s pop explosion. Importantly, both followers of Manson and Manson himself have noted how he did not otherwise draw on the music of sixties counterculture for inspiration; he was a disciple of the post war crooners (Sinatra, Perry Como, Bing Crosby etc) and like the composers of the ‘White Album’ drew on whatever felt right to express feeling and emotion through song. Charles Watson claimed that when he first listened to the ‘White Album’ with Manson in December 1968 he “ran from him” and devotion to the record was intense. Author Joan Didion named her account of the madness and paranoia of the age after the record (the most disturbing thing about the Tate-La Bianca murders amongst Didion’s LA tribe was her recollection that “no one was surprised”). Groups like the Rolling Stones packaged and resold violence and revolt in an immature and egotistical way. The Beatles’ form of the occult was more complex, hidden and more profound. ‘Lance Fairweather’ made an interesting comment when he said that: “If Abbey Road had come out sooner, maybe there would not have been a murder, maybe Sharon Tate would be alive today.” But then Abbey Road had its dark moments, too.

Manson’s association with the giants of rock music became a kind of creepy subconscious epitomising the time when rock met the counterculture, the moment when revolt rubbed shoulders with wealth. With the Beach Boys (through their drummer and hidden genius Dennis Wilson, who called Manson “the wizard”) this was a physical connection. With the Beatles it was psychic, imaginary. Manson deliberated over the Beatles’ eponymous 1968 LP (aka the ‘White Album’) with the studious devotion of a monk. It’s no surprise that he and his followers became obsessed with that record and that Beatles’ lyrics were repeated in Manson ‘sermons’ (“The glass onion is the door of water and the hole in the ocean is the pool in Death Valley”). Manson quoted The Ballad Of John And Yoko — identifying himself with the Christ figure in the song. The Manson reading of the ‘White Album’ was the first of many such fascinations with the record’s sound, image and content. Early Manson historians such as Bugliosi and Ed Sanders detected the eerie power of the record. Its minimalist blank white cover invites open interpretation, the kinds of experimental freethinking that the epoch — through mind-altering chemicals and radical head theories — invoked. The LP seems to speak to the future of rock music whilst detonating the idealism and egotism of the 1960s pop explosion. Importantly, both followers of Manson and Manson himself have noted how he did not otherwise draw on the music of sixties counterculture for inspiration; he was a disciple of the post war crooners (Sinatra, Perry Como, Bing Crosby etc) and like the composers of the ‘White Album’ drew on whatever felt right to express feeling and emotion through song. Charles Watson claimed that when he first listened to the ‘White Album’ with Manson in December 1968 he “ran from him” and devotion to the record was intense. Author Joan Didion named her account of the madness and paranoia of the age after the record (the most disturbing thing about the Tate-La Bianca murders amongst Didion’s LA tribe was her recollection that “no one was surprised”). Groups like the Rolling Stones packaged and resold violence and revolt in an immature and egotistical way. The Beatles’ form of the occult was more complex, hidden and more profound. ‘Lance Fairweather’ made an interesting comment when he said that: “If Abbey Road had come out sooner, maybe there would not have been a murder, maybe Sharon Tate would be alive today.” But then Abbey Road had its dark moments, too.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

Outsider Music?

The process of recording music kills spontaneity

Manson’s recording sessions were few. The release of his music has been covert and, in terms of quality, erratic. This is a symptom of the general conflict between Manson and the music business. As a free spirit, guided by whim, Manson is the sort of musical artist that confounds the production of highly commodified recorded music. Manson believed that music was the key to communicating ideas: “Music doesn’t know time, music is soul… it stays in your infinite unconscious.” On Manson’s first recordings it is discernible that he feels, like most first time recording artistes, uncomfortable: giggling nervously; self conscious. The process of recording music kills spontaneity and so in this respect Manson was in accord with the key figures in the folk revival of the 1950s who detested the reduction of love and communal forms of music-making by the industrialisation of folk music to another product for mass consumption. The intrusive aspect of studio recording frustrated Manson. “I never really dug recording. You go into the studio and it’s hard to sing into microphones,” he said. The obsession with a perfect recording, with total separation, making mixing smoother, was impossible to apply to the manner in which Manson and his ‘group’ liked to perform. An insight into the spontaneous nature of Manson’s creativity is sometimes captured in filmed interviews. During one interview for example, Manson attempts to launch into a spontaneous percussive improvisation with a plastic waste bin. As might a jazz musician, Manson improvises his way out of a corner. “I am my music. I play my music for me,” was his refrain.

Manson’s recording sessions were few. The release of his music has been covert and, in terms of quality, erratic. This is a symptom of the general conflict between Manson and the music business. As a free spirit, guided by whim, Manson is the sort of musical artist that confounds the production of highly commodified recorded music. Manson believed that music was the key to communicating ideas: “Music doesn’t know time, music is soul… it stays in your infinite unconscious.” On Manson’s first recordings it is discernible that he feels, like most first time recording artistes, uncomfortable: giggling nervously; self conscious. The process of recording music kills spontaneity and so in this respect Manson was in accord with the key figures in the folk revival of the 1950s who detested the reduction of love and communal forms of music-making by the industrialisation of folk music to another product for mass consumption. The intrusive aspect of studio recording frustrated Manson. “I never really dug recording. You go into the studio and it’s hard to sing into microphones,” he said. The obsession with a perfect recording, with total separation, making mixing smoother, was impossible to apply to the manner in which Manson and his ‘group’ liked to perform. An insight into the spontaneous nature of Manson’s creativity is sometimes captured in filmed interviews. During one interview for example, Manson attempts to launch into a spontaneous percussive improvisation with a plastic waste bin. As might a jazz musician, Manson improvises his way out of a corner. “I am my music. I play my music for me,” was his refrain.

More broadly, anyone familiar with the machinations of the music business will recognise the way in which Manson was ‘ripped-off’ by producers, the administrators and legal guardians of the industry. The entertainment industry in California found Manson and his followers interesting and various film projects capturing their crazy lifestyle and behaviour were planned. “I really appreciate your talent Charlie, but there’s nothing I can do for you,” Terry Melcher eventually told Manson. But was it Manson’s limitations that were at fault or the music business’ lack of imagination? Despite allowing the Beach Boys permission to use one of his songs Manson was never paid. “You know what Manson? You’re a flaky little nothing,” he was told when he went to recoup the royalties that he was owed. Manson did not forget the way he was treated by the music industry. “If you’ve lied and broken someone’s trust, I have no control over what happens,” he told one disgruntled bootlegger of his music. Manson’s official psychiatric diagnosis is that he is a “passive-aggressive personality with paranoid tendencies”. I can think of few better descriptions of the psychology of pop and rock stars.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

Jail Guitar Doors

Before the killings linked to Manson, his music was a meandering search for a timeless, spiritual life

Manson’s guitar playing is worth scrutinising in greater detail. A guitar has always been one of his most prized possessions. His guitar is supposedly buried somewhere in Death Valley “awaiting his escape”. Unlike most folk rock of the time and the blues tradition of steel string guitar playing, he prefers to use a nylon strung Spanish guitar and never finger-picks his guitar. This kind of guitar is difficult to impose in a dominant way over vocals and other instruments as it is clearly designed to be played solo or with a single vocal accompaniment (think of the British singer-songwriter Jake Thackray). While Manson is often associated with psychedelic rock guitarist Bobby Beausoleil, it is clear to see that he was never a pop or rock musician in the traditional sense. In addition to the type of guitar Manson used, his chord progressions go beyond the usual forms of pop and rock music. He makes use of the sixth and unresolved major seventh chords that are more commonly found in Latin music. Manson frequently uses open chords that ring out more forcefully (E and A major and minor chords). This style marks Manson’s music as out of the ordinary. There are elements of blues in Manson’s music but it is nearer to the blues of the desert, a sacred place for the Family. But then traditional blues music is an assertion of an aggressive form of male sexuality, something not clearly exhibited in Manson’s songs. Manson performed as a troubadour, as Life magazine dubbed him: a “roving minstrel”.

Manson’s guitar playing is worth scrutinising in greater detail. A guitar has always been one of his most prized possessions. His guitar is supposedly buried somewhere in Death Valley “awaiting his escape”. Unlike most folk rock of the time and the blues tradition of steel string guitar playing, he prefers to use a nylon strung Spanish guitar and never finger-picks his guitar. This kind of guitar is difficult to impose in a dominant way over vocals and other instruments as it is clearly designed to be played solo or with a single vocal accompaniment (think of the British singer-songwriter Jake Thackray). While Manson is often associated with psychedelic rock guitarist Bobby Beausoleil, it is clear to see that he was never a pop or rock musician in the traditional sense. In addition to the type of guitar Manson used, his chord progressions go beyond the usual forms of pop and rock music. He makes use of the sixth and unresolved major seventh chords that are more commonly found in Latin music. Manson frequently uses open chords that ring out more forcefully (E and A major and minor chords). This style marks Manson’s music as out of the ordinary. There are elements of blues in Manson’s music but it is nearer to the blues of the desert, a sacred place for the Family. But then traditional blues music is an assertion of an aggressive form of male sexuality, something not clearly exhibited in Manson’s songs. Manson performed as a troubadour, as Life magazine dubbed him: a “roving minstrel”.

Before the killings linked to Manson, and before the sixties dream fell the wrong side of the razor’s edge, his music was a meandering search for a timeless, spiritual life in place of the exterior controls of the state mechanism. Manson himself eventually said: “How are you going to get to the establishment? You can’t sing to them.” Jeff Nuttall suggested of this time that the outlaw’s gesture and his honesty might “lead to public murder”. So it proved. Manson’s music is the perfect expression of how when “pleasure is outlawed, and people who celebrate love openly are jailed, violence has become a way of attaining intimacy with other humans” (George Paul Csicsery). Perhaps there is some glimpse of this in the songs that Manson composed, but what we hear is not the adolescent worship of a death cult that his imitators have turned out. His statement: “Music seldom gets to grownups. It gets through to the young mind that’s still open,” reveals the importance of sound in communicating ideas and thoughts. Hence the fearful power of music: to alter consciousness and open minds to influence like a drug.

Charles Manson’s own opinion of his forays with and without other Family members into the world of rock stardom are sanguine: “I guess the girls and I blew it.” “Manson was striking out at the establishment,” Bugliosi told me and the music establishment was clearly part of that target. An early review of Manson’s LIE LP ended “Charles Manson, the record industry welcomes you with open arms.”

They never did.

Of the recordings currently available of Charles Manson’s music none are official releases. Even LIE is a collection of high quality demos elevated to the status of a proper LP. This is one reason why it is easy to dismiss Manson’s music: it sounds rough and incomplete. But perhaps this is how Manson should be confronted. Manson was never about capturing an essence on tape but about the expression of a moment. There follows a review of the key Manson recordings. It is not exhaustive as many recordings have been sneaked out of whichever prison Manson resides. It is still better to listen to Manson’s original music than anything that came after.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

LIE (1970)

ESP-Disk/Awareness ESP 2003

[su_spacer size=”40″]

[su_quote cite=”from the sleeve notes to LIE”]I got some music that says what I like to say if I ever had anything to say[/su_quote]

LIE was recorded in Sound City studios, Van Nuys exactly one year before the date of the Tate-La Bianca killings. The recording were initially issued by Phil Kaufman and of the original 2,000 copies, by 1972 less than 300 had been sold. Kaufman’s record label was called Awareness a reference to Manson’s claim that he held special powers of perception: “I look into the future like an Indian on a trail.” The cover image is now legendary and features a police photograph of Manson that was taken in 1968 when he was arrested on an auto theft charge. The ‘mad’ hypnotic stare was to become the defining image of Manson, an image as loaded as Albert Korda’s portrait of ‘Che’ Guevara, a man capable of the same hypnotic power. Free ads for the LP ran in many underground and countercultural newspapers of the time. Profits from Kaufman’s issue of the record were said to be in support of Manson’s legal defence; now they supposedly go to his victims.

LIE was recorded in Sound City studios, Van Nuys exactly one year before the date of the Tate-La Bianca killings. The recording were initially issued by Phil Kaufman and of the original 2,000 copies, by 1972 less than 300 had been sold. Kaufman’s record label was called Awareness a reference to Manson’s claim that he held special powers of perception: “I look into the future like an Indian on a trail.” The cover image is now legendary and features a police photograph of Manson that was taken in 1968 when he was arrested on an auto theft charge. The ‘mad’ hypnotic stare was to become the defining image of Manson, an image as loaded as Albert Korda’s portrait of ‘Che’ Guevara, a man capable of the same hypnotic power. Free ads for the LP ran in many underground and countercultural newspapers of the time. Profits from Kaufman’s issue of the record were said to be in support of Manson’s legal defence; now they supposedly go to his victims.

In these recordings we hear what Jakobson noted was Manson’s “early form of Rap”. A percussive beat on the guitar is overlayed with a free flow of consciousness, thoughts and expressions located in both the internal space and via external manifestations (flies buzzing, his shoes, someone passing by). Manson plays his songs here to relay his philosophy. Manson was accompanied by Paul Watkins and Bobby Beausoleil. Some of the more complex electric guitar lines belonged to the latter.

Beausoleil once observed that “Charlie doesn’t have a whole lot of talent” and Dennis Wilson observed that “Charlie did not have a musical bone in his body”. This is the myth that has grown up around Manson and his music and one can hear from this recording that this is wrong.

Look At Your Game Girl has a plaintive opening with strummed single chords. “Time keeps on flying” mourns Manson and in this moment you can feel how his charisma hypnotized so many. Anyone listening closely this song will feel this transference of energy and motion. Manson said of Ego: “Ego is the man, the male image” and this song is clearly a denunciation of the male psyche. “You can’t stand not be right” and “Ego is a too much thing” sings Manson. The backing on this track is a strong blend of congas and sitar, augmented with improvised violin (Manson’s violinist was usually Catherin Share, aka Gypsy) and occasional blasts from a hunting horn. The unusual blend of instruments is reminiscent of early Incredible String Band. Mechanical Man is a song about people versus the machine, a common countercultural scenario. It is also about how humans become machines and recalls Charles Watson’s description of how he felt during the murders: “I felt like a mechanical man, a programmed machine out of control, like a malfunctioned robot unable to stop the brutality.” It begins with imitations of mechanical sounds and a spoken-word section. The song becomes a powerful drone and recalls early Velvet Underground. Female voices cut in and out; one of them wails in despair. The music becomes more frantic and chaotic. The autobiographical line “I am my mother’s toy” draws on Manson’s childhood years of neglect. The theme of the song later inspired the musical and lyrical preoccupations of the new wave band Devo who like Manson hailed from Ohio. People Say I’m No Good reflects Manson’s own feelings of rejection. It begins as a mournful cry with sparse accompaniment from his nylon-stringed guitar. But soon it becomes more strident and the internal pain and frustration becomes defiantly anti-establishment, against conformity, casting blame outwards: “Look at the fix they’re in…the young might be so dumb after all.” This section of the song is very percussive with a strong bongo rhythm. The poetic flourish ends with the spoken phrase “cancer of the mind”. Home is Where You’re Happy proclaims the peace brought about from the creation of a true ‘family as opposed to the official nuclear version that many of Manson’s followers suffered terribly under. “You’ll never be alone” is the positive alternative vibe sent out. There are more Sterling Morrison-inflected guitar lines in Arkansas and on this track female vocals are prominent, breathy at the beginning, spoken, decrying ‘struggle’ before Manson interjects with the song proper. I’ll Never Say Never to Always is interesting in that the ambience of Family musical get-togethers can be clearly discerned. There are babies crying in the background and the whole effect, a good snapshot of the communal experience of the Family, is of a Sunday school choir reciting an ode to spiritual joy. Garbage Dump reveals Manson’s long-standing eco-concerns: “You can feed the world with my garbage dump,” a belief that was realised in the infamous family  ‘garbage runs’ to collect cast off food from supermarket bins (still a common eco-warrior practice). Manson’s sense of humour is manifest at the end. Don’t Do Anything Illegal has the feel of an Eastern drone — another clichéd character of 1960s music, augmented by fine electric guitar work courtesy of Beausoleil. “The eagle has got you by the neck” sings Manson, a clear indictment of American state oppression. Sick City castigates those that “sit at home and drink your beer.” With Cease To Exist the most famous song on LIE, it is clear why the Beach Boys were keen to record it. Dennis Wilson changed the lyrics lifting the line “Never learn not to love you” as the new title — an act that infuriated Manson (Manson: “Dennis Wilson was killed by my shadow because he took my music and didn’t pay me and changed the words from my soul, sound songs”). The version that appeared on the Beach Boys recordings uses the common 1960s technique of time shifts (4/4 to 3/4 time) and begins with an eerie swell of discordant noise (a tape run backwards) before launching into the more familiar harmonies of the group. “Submission is a gift” intones the dark aesthetics of countercultural drug philosophy. For Manson, the meaning of the words as they come out of your mouth is the truth. It should not be altered – especially for some crass commercial purposes. In Cease To Exist Manson relates his philosophy as outlined in the following quote: “You are not you, you are just a reflection, you are reflections of everything that you think that you know, everything you have been taught.” Big Iron Door is a dark portrait of incarceration in American prisons, again switching time signatures from slow to fast and intense. The minor key and discordant chord changes add to the feel of disorientation. I Once Knew A Man begins with Spanish guitar inflections and frantic conga/maraca support. One can imagine this song ringing out across the desert, a freak-out cri de cour. As if to underline the commercial potential of Manson’s compositions, the final track on LIE, Eyes Of A Dreamer, has lovely acoustic guitar lines and gallops along in a style closely resembling a Walker Brothers tune.

‘garbage runs’ to collect cast off food from supermarket bins (still a common eco-warrior practice). Manson’s sense of humour is manifest at the end. Don’t Do Anything Illegal has the feel of an Eastern drone — another clichéd character of 1960s music, augmented by fine electric guitar work courtesy of Beausoleil. “The eagle has got you by the neck” sings Manson, a clear indictment of American state oppression. Sick City castigates those that “sit at home and drink your beer.” With Cease To Exist the most famous song on LIE, it is clear why the Beach Boys were keen to record it. Dennis Wilson changed the lyrics lifting the line “Never learn not to love you” as the new title — an act that infuriated Manson (Manson: “Dennis Wilson was killed by my shadow because he took my music and didn’t pay me and changed the words from my soul, sound songs”). The version that appeared on the Beach Boys recordings uses the common 1960s technique of time shifts (4/4 to 3/4 time) and begins with an eerie swell of discordant noise (a tape run backwards) before launching into the more familiar harmonies of the group. “Submission is a gift” intones the dark aesthetics of countercultural drug philosophy. For Manson, the meaning of the words as they come out of your mouth is the truth. It should not be altered – especially for some crass commercial purposes. In Cease To Exist Manson relates his philosophy as outlined in the following quote: “You are not you, you are just a reflection, you are reflections of everything that you think that you know, everything you have been taught.” Big Iron Door is a dark portrait of incarceration in American prisons, again switching time signatures from slow to fast and intense. The minor key and discordant chord changes add to the feel of disorientation. I Once Knew A Man begins with Spanish guitar inflections and frantic conga/maraca support. One can imagine this song ringing out across the desert, a freak-out cri de cour. As if to underline the commercial potential of Manson’s compositions, the final track on LIE, Eyes Of A Dreamer, has lovely acoustic guitar lines and gallops along in a style closely resembling a Walker Brothers tune.

The general consensus about LIE (and indeed all of Manson’s music) seems to be ‘Well, I’ve heard worse’. But LIE clearly demonstrated why Manson led the musical activities of the Family. While other Family members are noted to be ‘better’ musicians (Beausoleil, Share, Grogan), listening to this collection of songs, it is clear that Manson had by far the richest voice and a unique style that mere technical efficiency cannot attain. He made effective use of his “total energy”. Ed Sanders is not the only one who believed that Manson “could have been a big star”.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

THE ’67 SESSSIONS (‘THE SUMMER OF HATE’) (2007)

Arte Lupo L182

Recorded at Gold Star Studios, Hollywood, November 1967. Produced by Gary Stromberg. These were the earliest recordings of Manson’s music and have a quality even rougher than the recordings that made LIE. Here, Manson, generally unaccompanied, is less confident than he sounds on LIE and intersperses the songs with general chatter, raps, laughing and a long string of aphorisms. Nevertheless, the songs are some of Manson’s best and are worth examining in greater detail. The energy levels are tangibly more heightened compared to later recordings. The musicality of Manson’s songs cuts through.

Recorded at Gold Star Studios, Hollywood, November 1967. Produced by Gary Stromberg. These were the earliest recordings of Manson’s music and have a quality even rougher than the recordings that made LIE. Here, Manson, generally unaccompanied, is less confident than he sounds on LIE and intersperses the songs with general chatter, raps, laughing and a long string of aphorisms. Nevertheless, the songs are some of Manson’s best and are worth examining in greater detail. The energy levels are tangibly more heightened compared to later recordings. The musicality of Manson’s songs cuts through.

Devil Man draws on the blues spirit of early American popular music. A simple two-chord phrase is repeated and then speeds up. Manson’s subconscious spills out in to the track: “the devil man swings the blues.” The More You Love also utilises a simple two-chord tonal refrain overlayed with the kind of skeining melody that characterises many 1960s outlaw songs. Phrases expressing an attack on hypocrisy that Manson clearly found appealing get thrown into the songs such as ‘the sound of one-hand clapping’ and become repetitive chants. Two Pair Of Shoes deals with one of Manson’s pet hates: consumer waste culture. Here Manson’s preference for major sixth guitar chords (which can be played accidentally) is striking. Maiden With Green Eyes (Remember Me), although driven by a rumba rhythm, has a medieval narrative sensibility but also the tone of 1950s doo-wop that Manson grew up with. The phrase “remember me” would not sound out place in songs by Bobby Vinton, Dion or John Leyton. Swamp Girl although like all these tracks sparse manages to feel operatic with its frequent shifts and varied sections. Bet You Think I Care has a smooth chord progression akin to Simon and Garfunkel’s The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy) and exhibits the folk/pop style that flooded America and the UK in the early 1960s. Another favourite Manson guitar trick heard here is the semi-tone/tone slide chord. True Love You Will Never Find, Invisible Tears, This Is Night Life and My World are brilliant folk protest/doo-wop hybrids. Invisible Tears should have been used by Kenneth Anger in Scorpio Rising and the latter, with its clever key change would have happily worked in a David Lynch film. The House Of Tomorrow opens with Manson claiming “this will make you a lot of money” and it could pass for a competent late sixties peace song. Close To Me is structured around jazz progressions. Perhaps Sinatra could have performed it? “I got some songs that other people could sing” introduces a medley of three tunes that complete the recordings supposedly written by a fellow con and based on prison life — loss, deceit, loneliness. It is a narrative concluding with the release and return to family life.

This session also features earlier versions of Look At Your Game Girl, People Say I’m Good (Who To Blame here) and Sick City, slower and less atmospheric versions than the later recordings on LIE. Despite encouragement from producer Gary Stromberg to “do whatever comes into your head”, it’s clear that the sheer range of styles and forms that Manson draws on only to abandon when he gets bored would have been hard for any executive to ‘market’.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

CHARLES MANSON LIVE AT SAN QUENTIN (1996)

Grey Matter GM01LP UK 1993

This low-fi recording is one of the more recent records of Manson’s musical output. San Quentin is a place of strong resonance for Manson. He was originally lodged here on death row after his trial and sentence in 1970. He has returned to the prison on several occasions since them. On the occasion of his return in 1985, when a piece of hacksaw blade was found hidden in his shoe, these live recordings were made. The tile of the record pays homage to the legendary concert by Johnny Cash made and recorded at the prison in February 1969.

This low-fi recording is one of the more recent records of Manson’s musical output. San Quentin is a place of strong resonance for Manson. He was originally lodged here on death row after his trial and sentence in 1970. He has returned to the prison on several occasions since them. On the occasion of his return in 1985, when a piece of hacksaw blade was found hidden in his shoe, these live recordings were made. The tile of the record pays homage to the legendary concert by Johnny Cash made and recorded at the prison in February 1969.

This recording presents the latest in reflections on the state of mind of Manson. It offers an interesting glimpse into what an audience with Manson is like, reverting from songs to philosophising and the constant interruptions of everyday life into the Manson space. The songs are improvised. Television Mind demonstrates Manson’s capacity still for critiquing consumer, technological culture.

The cover is interesting, designed as it is to look like the Beach Boys legendary but over-rated Pet Sounds LP. Pressed on yellow vinyl, the original sleeve was a picture taken through a wire fence of Manson being led by guards through the prison grounds. The CD used a colour picture of a wizened Manson holding his highly decorated acoustic guitar.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

THE MANSON FAMILY SINGS THE SONGS OF CHARLES MANSON (‘FAMILY JAMS’) (1986)

No Label L-36974

Manson’s ‘lost’ songs recorded in 1970 by Family members, including Steve Grogan (guitar), Brenda and Country Sue (vocals) and Catherine Share (violin).

This much-maligned LP is often characterised as being a recording of Manson’s brainwashed dupes singing around the campfire in sympathy and association with the absence of Charles Manson’s body through the continuum of his spirit through musical means. “How can they sound so happy when they are vicious murderers?” seems to be the general line of enquiry. The answer to this is not that difficult. The people involved in this recording are expressing their own world, the haven of the desert and their ranches, the wide open spaces, the natural elements, the retreat to Death Valley and the AIR FIRE WATER TREES philosophy that would later define Manson’s post confinement actions. These songs epitomise ‘desert music’ a statement of friendship and faith in Manson and his beliefs. Again, the quality of the recordings does not assist easy engagement with the music on the record. As Jeff Nuttall once noted of the 1960s: “Young people are not correcting society. They are regurgitating it”. The Manson family would gather under the clear skies and stars to sing these songs. They continued to intone the songs at Manson’s defence, the beautiful harmonies seeming eerie in the context of a mass-murder trial. Steve Grogan appears the most prominent performer on these recordings but the Manson ‘girls’ provide a haunting (heavily drenched in reverb) chorus as backing (but not always ‘backing’ as they sing the main lines of the songs as well as ‘call and response’ vocals). The songs are noticeably darker than the earlier solo Manson recordings, lacking any sense of the humour present in those sessions. The opening driving track in a minor key Ra-Hide Away pleads that they “let him go”. The song is a western epic set to communal folk singing. The Fires Are Burning is a terrifying and atmospheric minor-key song mythologizing the intense heat of love. If you were looking for a song to epitomise the dark hypnotic power of the psyche of Manson’s Family then Die To Be One would be it. A plaintive violin played by Share wavers throughout the song. Die To Be One is a continuation of the Cease To Exist philosophy: come together, lose your ego, become nature, death is a new beginning. “Up the valley of death they come” begins No Wrong — Come Along as witchy chants lure the wanderer and lost soul into the realms of the Family. The calls heard are those of the coyote howls loved and revered by Manson. Get On Home is a roots song about the natural world of the drop-out farmscape. Is There No One In Your World But You? contains a haunting and evocative ghostly backing chorus. First They Made Me Sleep In The Closet uses a cheery and comic setting for a dire tale of childhood neglect (a favourite Manson theme). The record also includes the unofficial Family anthem I’ll Never Say Never To Always here performed with a guitar backing. The maniacal laughing that opens If I Had A Million Dollars — extended beyond the duration that would be comfortable — still has the power to disturb.

This much-maligned LP is often characterised as being a recording of Manson’s brainwashed dupes singing around the campfire in sympathy and association with the absence of Charles Manson’s body through the continuum of his spirit through musical means. “How can they sound so happy when they are vicious murderers?” seems to be the general line of enquiry. The answer to this is not that difficult. The people involved in this recording are expressing their own world, the haven of the desert and their ranches, the wide open spaces, the natural elements, the retreat to Death Valley and the AIR FIRE WATER TREES philosophy that would later define Manson’s post confinement actions. These songs epitomise ‘desert music’ a statement of friendship and faith in Manson and his beliefs. Again, the quality of the recordings does not assist easy engagement with the music on the record. As Jeff Nuttall once noted of the 1960s: “Young people are not correcting society. They are regurgitating it”. The Manson family would gather under the clear skies and stars to sing these songs. They continued to intone the songs at Manson’s defence, the beautiful harmonies seeming eerie in the context of a mass-murder trial. Steve Grogan appears the most prominent performer on these recordings but the Manson ‘girls’ provide a haunting (heavily drenched in reverb) chorus as backing (but not always ‘backing’ as they sing the main lines of the songs as well as ‘call and response’ vocals). The songs are noticeably darker than the earlier solo Manson recordings, lacking any sense of the humour present in those sessions. The opening driving track in a minor key Ra-Hide Away pleads that they “let him go”. The song is a western epic set to communal folk singing. The Fires Are Burning is a terrifying and atmospheric minor-key song mythologizing the intense heat of love. If you were looking for a song to epitomise the dark hypnotic power of the psyche of Manson’s Family then Die To Be One would be it. A plaintive violin played by Share wavers throughout the song. Die To Be One is a continuation of the Cease To Exist philosophy: come together, lose your ego, become nature, death is a new beginning. “Up the valley of death they come” begins No Wrong — Come Along as witchy chants lure the wanderer and lost soul into the realms of the Family. The calls heard are those of the coyote howls loved and revered by Manson. Get On Home is a roots song about the natural world of the drop-out farmscape. Is There No One In Your World But You? contains a haunting and evocative ghostly backing chorus. First They Made Me Sleep In The Closet uses a cheery and comic setting for a dire tale of childhood neglect (a favourite Manson theme). The record also includes the unofficial Family anthem I’ll Never Say Never To Always here performed with a guitar backing. The maniacal laughing that opens If I Had A Million Dollars — extended beyond the duration that would be comfortable — still has the power to disturb.

The music on this record is a pale imitation of the effectiveness of the communal ‘family’ process of singing (compare to the quality of Lyman Family recordings for example). This is also the result of a poor recording process. Yet these recordings still demonstrate the effectiveness of Manson’s song writing skills, and show that he was easily as gifted as many more famous and legitimate singers and songwriters.

[su_spacer size=”40″]

[su_quote cite=”Bobby Beausoleil”]Everything in life is good. It all flows. It’s all good. It’s all music…[/su_quote]

[su_spacer size=”40″]

Charles Manson’s music is designed to connect and communicate with the outside world. If his records had been released officially (instead of endlessly bootlegged) it is estimated that they would qualify for a gold disc (sales over 500,000 copies). Manson’s music is a form of outsider art — the work of an autodidact musician with a totally unique presentation style and perspective. It is foolish to expect and believe that Manson’s music is a form of ‘devil rock’. The cover versions and tributes in this field and the tributes to his underground aesthetic have nothing at all do with his own musical expressions (they are more about reflecting and interpreting the myth of Manson built up over the last forty years). One of the reasons that Manson’s myth endures is that show business has found irresistible the lure of a charismatic and messianic musician who is capable of actual murder. Unlike the rockers who for years have played at being evil and dangerous (with dire consequences) Manson is a figure that carried those fantasies into reality. Like the early blues singers that sang of the despair in the world and then were tragically killed, Manson rears up as an image of the true face of human tragedy. Manson is described as a “natural product of what you get when you cross a groovy subculture with a brutalizing system” and music has a powerful role to play in this. The Manson crimes disappear but are internalized in the mental sphere leaving what Baudrillard calls an occult trace. Music plays an essential role in this process.

Charles Manson’s music is designed to connect and communicate with the outside world. If his records had been released officially (instead of endlessly bootlegged) it is estimated that they would qualify for a gold disc (sales over 500,000 copies). Manson’s music is a form of outsider art — the work of an autodidact musician with a totally unique presentation style and perspective. It is foolish to expect and believe that Manson’s music is a form of ‘devil rock’. The cover versions and tributes in this field and the tributes to his underground aesthetic have nothing at all do with his own musical expressions (they are more about reflecting and interpreting the myth of Manson built up over the last forty years). One of the reasons that Manson’s myth endures is that show business has found irresistible the lure of a charismatic and messianic musician who is capable of actual murder. Unlike the rockers who for years have played at being evil and dangerous (with dire consequences) Manson is a figure that carried those fantasies into reality. Like the early blues singers that sang of the despair in the world and then were tragically killed, Manson rears up as an image of the true face of human tragedy. Manson is described as a “natural product of what you get when you cross a groovy subculture with a brutalizing system” and music has a powerful role to play in this. The Manson crimes disappear but are internalized in the mental sphere leaving what Baudrillard calls an occult trace. Music plays an essential role in this process.

There may be other Manson recordings. Vincent Bugliosi told me that Dennis Wilson had made some recordings of Manson at Santa Monica but that he had destroyed the tapes: “The vibes were not of this world” Wilson alleged. Manson’s music, like most of what he did, is hated and feared. But this makes me think of the words of Thom Gunn:

The reason I detest you,..

Is the same reason I detest Charles Manson,

For his interpretation of songs on the White Album…

But he was less cynical than you, he believed in his interpretations, he acted on them

Perhaps Manson was not the only musician to kill the 1960s?

[su_spacer size=”40″]

This article originally appeared in Headpress 2.2 (July 2010)

Mark Goodall

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress