Dead: A Celebration of Mortality

Dead: A Celebration of Mortality contains 52 short essays to coincide with the Saatchi Gallery’s 2015 exhibition of the same name. Charles Saatchi is no stranger to controversy, from the furore surrounding 1997’s ‘Sensation’—an exhibition including Marcus Harvey’s notorious portrait of Myra Hindley—to 2001’s ‘I Am A Camera’, which attracted press attention after members of the public apparently complained about the inclusion of Tierney Gearon’s photographs of her two naked children. It is notable, then, that Dead contains relatively few images. Those that do appear, however, range from the benignly amusing (dogs driving cars, a huge Merino sheep) to the genuinely haunting, which are often placed in close proximity to one another to make their effect even more jarring. A photograph of a dead man hanging from a tree in the notorious Aokigahara forest at the base of Mount Fuji—an all too popular last resting place for many suicides—precedes a still from Jurassic Park where a dinosaur confronts a character sitting on the toilet. This merging of real and fictional deaths continues throughout the book, and the fact that there is no image credit or biographical information for the anonymous man hanging in the forest is itself testament to the pervasiveness of images of death in contemporary culture. Images once confined to the ‘underground’ press are here presented as profound and/or ridiculous artefacts, in a book that is to all intents and purposes a coffee-table book—to be leafed through at leisure, read cursorily and without much analysis.

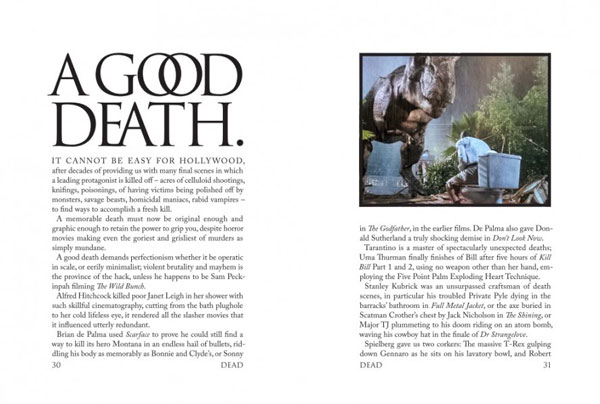

In some pieces, death does form a starting point to what promise to be broader historical narratives—of the myth and reality of the Wild West for example—but which quickly degenerate into Saatchi’s meandering down several barely-connected routes at once. In the five short pages of the Wild West piece, he covers the treatment of the Native Indian population, gun control laws, and female wrestling in a narrative that is as infuriating as it is tantalising. There are some fascinating glimpses into broader issues here, though. Saatchi describes the ‘living dead’ of Uttar Pradesh in India where, due to a combination of corrupt local government and overpopulation, many people very much alive are declared dead in order to get hold of their land. He is at his best when discussing the terminology of death: gallows humour, the language of the stock market and its life-altering crashes, and ‘the dead man’s switch’ (the safety feature built into trains that cuts all power should the driver become incapacitated, but which Saatchi considers alongside the ‘kill-switch’ of the suicide bomber and the Cold War ‘Dead Hand system’ that assured mutual nuclear destruction). These are the briefest of glimpses, however. The discussion of the Uttar Pradesh living dead quickly veers off into termites and burial rituals, and the dead man’s switch analogy is rather stretched into a discussion of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. Saatchi’s startling bounding from topic to topic becomes merely tedious at times (on page 217 he asks us ‘Are you being bored to death by this book?’), not least due to his penchant for lists. There are lists of deaths in feature films, deaths in literature, deaths at the hands/paws/jaws of pets, deaths on stage, and deaths by air crash that suggest Saatchi himself is indeed becoming bored to death by the whole thing.

Dead is both a coffee-table book and a sourcebook, with the condensed anecdotes and stories Saatchi offers serving as invitations to follow up on them in more detail than that offered here. It is slightly reminiscent of an Amok Dispatch devoid of references, as there is little content here that will be novel to those familiar with publications by Feral House and their ilk. Certainly, it’s earlier publications from these presses that the reader will likely end up at if they wish to investigate Saatchi’s snippets any further. For deaths at Disneyland, see David Koenig’s Mouse Tales; for snuff films, see David Kerekes and David Slater’s Killing for Culture; for auto-erotic fatalities, see Amok’s Sensurround Edition (or, to indulge your taste for amusing deaths more cheaply, simply peruse the Fortean Times’ ‘Strange Deaths’ column).

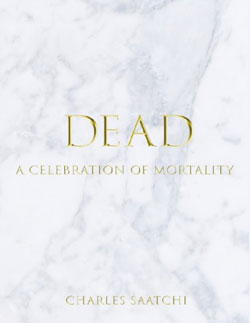

Dead’s primary attraction is as a physical object, styled as a heavy marbled tombstone with thick card covers and elegantly laid out inside. The placing of the book’s title close to the text at the bottom of each page is surely not an accident on Saatchi’s part, as the schlocky threat of ‘DEAD’ interrupts the reader’s flow every two minutes as a sort of shouted interjection. For such a nicely presented book, however, there are several proofing errors—such as the ‘rapid metal deterioration’ of Ricardo Lopez, who posted a bomb to Björk in 1996—that spoil what is an otherwise lavish production. The final page of the book suggests (barely even) a joke on Saatchi’s part: ‘Some lives leave a mark. Others leave a stain. Almost everybody lives a life of little consequence to mankind. But wouldn’t you prefer to have spent your years rather uselessly, but entertainingly—even if your existence didn’t achieve anything memorably significant at all?’ Regardless of the artistic pretensions behind it, Dead unfortunately contains little of significance or entertainment, and will be to many a simple case of style over substance.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress