Eerie Tales and Unsettling Stories: A Personal History of Teen Horror Fiction

My bookshelves are slowly but surely regressing back to childhood. One Bunty comic bought for nostalgia’s sake has spiralled into a shelf of carefully packaged back issues, and I’m not going to admit what I paid for the 1991 summer special. Sitting down with a favourite Point Horror novel from my early teens is an oddly comforting and immersive experience; I can almost hear my dad’s voice pleading that I read something other than “those horror books”.

Younger readers began to be taken more seriously as a market in the second half of the twentieth century, but it was in the 1990s that fiction targeted specifically at teenagers (or ‘Young Adults’) experienced something of a boom. Anthony McGowan makes a distinction between ‘teen fiction’ (aimed at 11–14 year olds) and Young Adult (YA) fiction (age 14 and up). This line between teen fiction and potentially racier YA fare was clearly signalled in my local library, with the YA selection quite literally top shelf. As young teenagers, my friends and I were also alert to the subtle variations in cover design that denoted whether a book would be considered slightly too ‘old’ for us – and therefore a desirable read. The Sweet Dreams series, with its cover girls in their late teens, blow-dried hair haloed around their heads, was infinitely preferable to the dull, age-appropriate, Baby-Sitters Club. The shimmering titles of Point Horror novels looked more like adult horror fiction than the colourful (to our eyes, childish) covers of R.L. Stine’s Goosebumps series.

YA horror was, as June Pulliam notes, a kind of bridge between children’s and adults’ literature, with the sexually explicit or gory elements of adult horror stripped out. Typical horror tropes were retained but dialled down: Point Horror plots frequently revolved around the stalking of a female character, or a group of friends terrorised by an unknown assailant.

But there was a preliminary step to take before you reached the heady heights of Point Horror, and that was the supernatural or horror anthology. Rather than drawing upon horror movie tropes, these collections contained more ghosts than gore. Mindful of the need to pacify protective parents and watchful librarians, very few anthologies contained the word ‘horror’ in the title. Instead, their contents were ‘sinister’, ‘unsettling’, ‘eerie’, ‘scary’, or ‘spooky’.

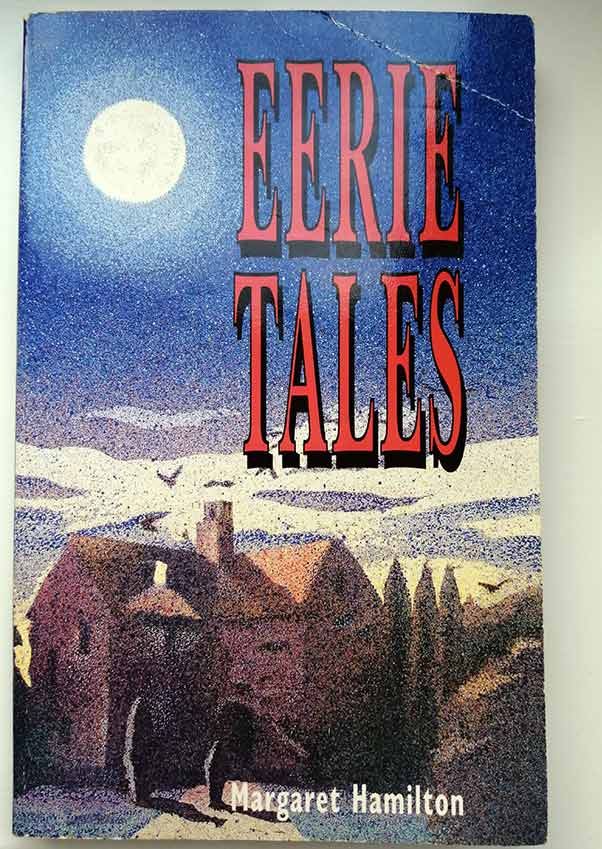

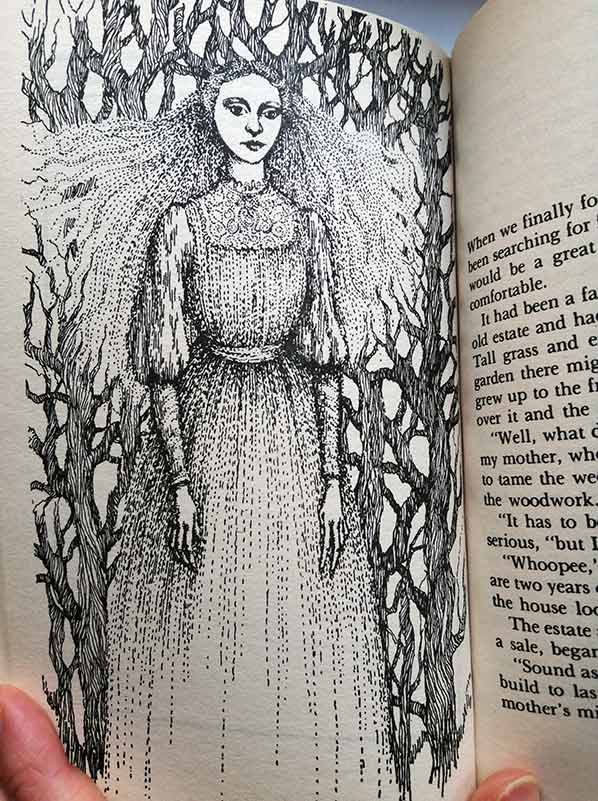

The first such collection I encountered was Eerie Tales (1992), a UK reissue of Australian anthology Spooks and Spirits (1978). Our school hosted regular events by The Book People, which sold books via local distributors. You ordered a book from their catalogue and it was given to you in class a week later. Eerie Tales’ unremarkable cover — I’d go so far as to say dull and uninspired — possibly allayed the concerns of my teacher as she handed it over, or it may have been that she was distracted by the other volume she had to dispense that day, Brad Pitt: Hot ’n’ Sexy. Although the stories within Eerie Tales were much of a muchness (almost all about haunted houses), the delicate line illustrations by Deborah Niland had an unsettling air to them and the volume whetted my appetite for tales of the weird.

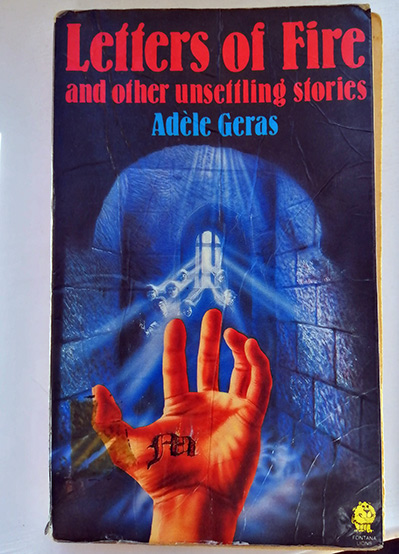

The library yielded another anthology that was to become a firm favourite: Adèle Geras’s Letters of Fire and other unsettling stories (1984). Published under the Fontana Lions imprint, this contained good old-fashioned ghost stories given a modern twist that rendered them less threatening for younger readers. In ‘The Graveyard Girl’, Teresa Wignall is the class ghost:

A surprise! Teresa can float over the highest boxes with no effort at all. She can balance on the narrowest bar of all, she seems almost to be weightless. Mrs. Pike is delighted and lavish with her praise.

The most memorable story of this anthology, though, was ‘The Dollmaker’. This is an unnerving and rather grotesque tale about Avril Clay, an elderly lady who runs a doll repair service for local children. The children’s belief that the dolls are returned to them with slightly different hair or eye colour haunts them: ‘…sometimes at night, she dreamed of Auntie Avril, peeling away the layers of Alice’s soft skin with her bare hands.’ As a child I never saw the end of the story coming. Although the twist seems glaringly obvious now, I don’t think that renders it any less unnerving. A new girl arrives at school who is introduced as an orphaned relative of Avril Clay’s:

“I don’t believe it!” Jackie was shouting. “I just don’t believe it! Look at her! Look at her hair and her skin! I think Auntie Avril stole bits from all our dolls, and probably from others as well, and made herself a person, that’s what I think!”

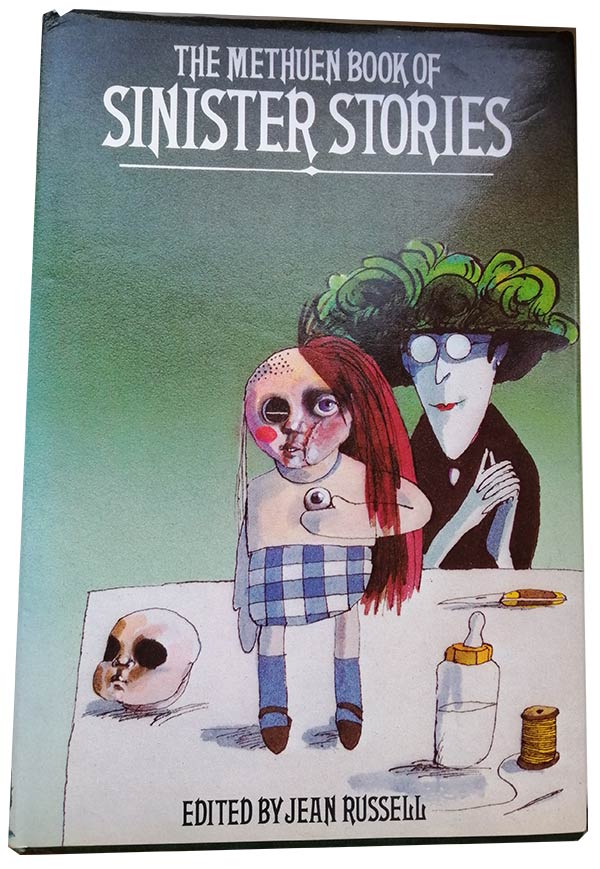

‘The Dollmaker’ had previously been included in The Methuen Book of Sinister Stories (1982). Edited by Jean Russell, a former librarian and lifelong advocate for children’s literature, the cover design by Tony Ross is unusually striking and part of the reason I was compelled to track down a copy online. It is, I think, the perfect example of the young teen horror anthology. There is the obligatory humorous story in ‘Miss Hooting’s Legacy’, about a family landed with two ramshackle robots that cause complete chaos, but there are also some beautifully crafted and genuinely ‘sinister’ tales that explore weightier topics. I remain unsettled by ‘Mister Mushrooms’, Robert Swindells’ re-imagining of German spies and secret weaponry during World War II. Gene Kemp’s ‘The Passing of Puddy’ and Joan Phipson’s ‘Black Dog’ are poignant portrayals of the sometimes uncanny connection between children and animals. There are also darker offerings, with nods to folklore in ‘Spring-heeled Jack’ (Gwen Grant), and echoes of the antiquarian ghost stories of M.R. James in ‘The Book of the Black Arts’ (Patricia Miles). Rereading Sinister Stories now, I’m impressed by its balance of the light-hearted and the serious, constructing a space where fantasy is a means of exploring serious issues.

There’s a lot of talk about comfort reading at the moment, with many of us weathering COVID-19 by burrowing into old favourites. Old favourite or not, you could do much worse than track down an old copy of Methuen’s Sinister Stories for some entertaining, and pleasingly unsettling, night-time reading.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress

One Response