What is Biblio-Curiosa?

The other day I was listening to a podcast. It’s a music podcast that plays old and new punk/garage/rock type stuff. Bands I hadn’t heard of before I find I sometimes like, so I keep listening. Sometimes there are guests on the show who volunteer their favourite tracks. One recent guest was a fellow with showbiz connections who had been around the block a few times. He was full of punk rock anecdotes, but with an attitude that was entirely retroactive, like a crumbling old man on a park bench waxing lyrical about Splodgenessabounds. New bands, whose names he mispronounced, were probably not good. Conversely, the many gigs he had attended down the years were all great and the bands he had seen were great or dead or both and everyone who was dead was great, including Mark E. Smith. He would much prefer that kids — kids, a word he used — stopped listening to the bands they liked and listen instead to the bands that he liked. This to me seemed the crux of it. Self-serving eulogizing, evidenced here, is a malady that is best avoided. It tries to posit that good things can only ever happen in the past. On a show devoted to punk/garage/rock type stuff, such an attitude makes even less sense because it implies that creativity — the so-called do-it-yourself aesthetic — has a finite shelf life. In other words, why bother? Give up now because it’s gone forever.

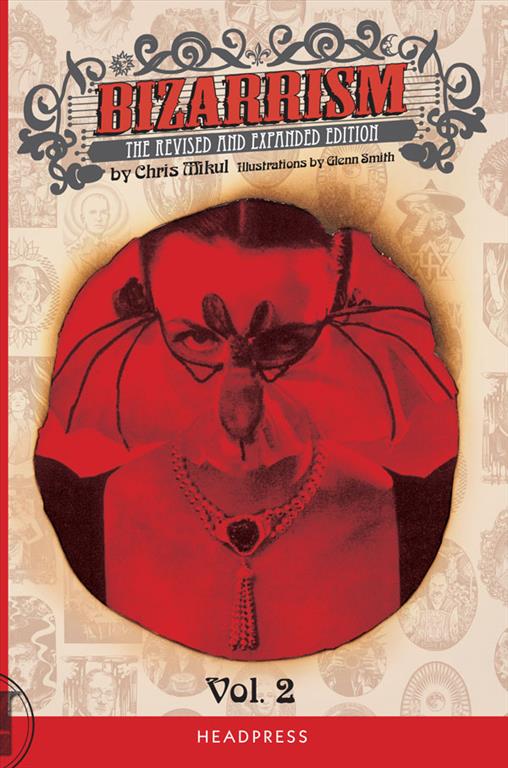

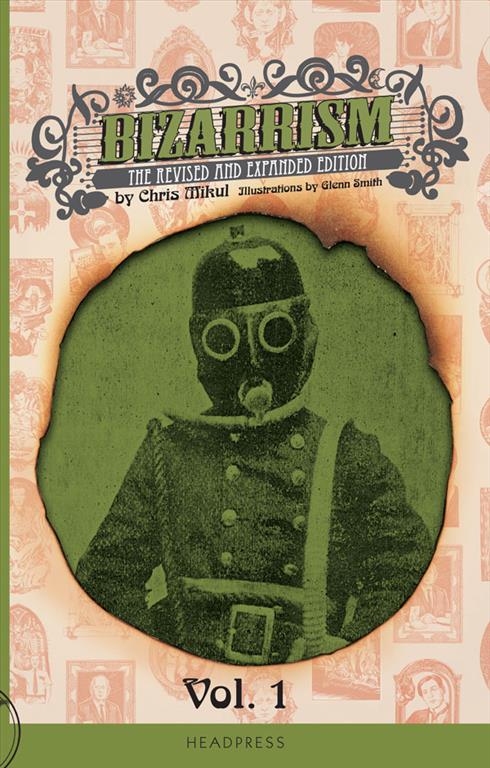

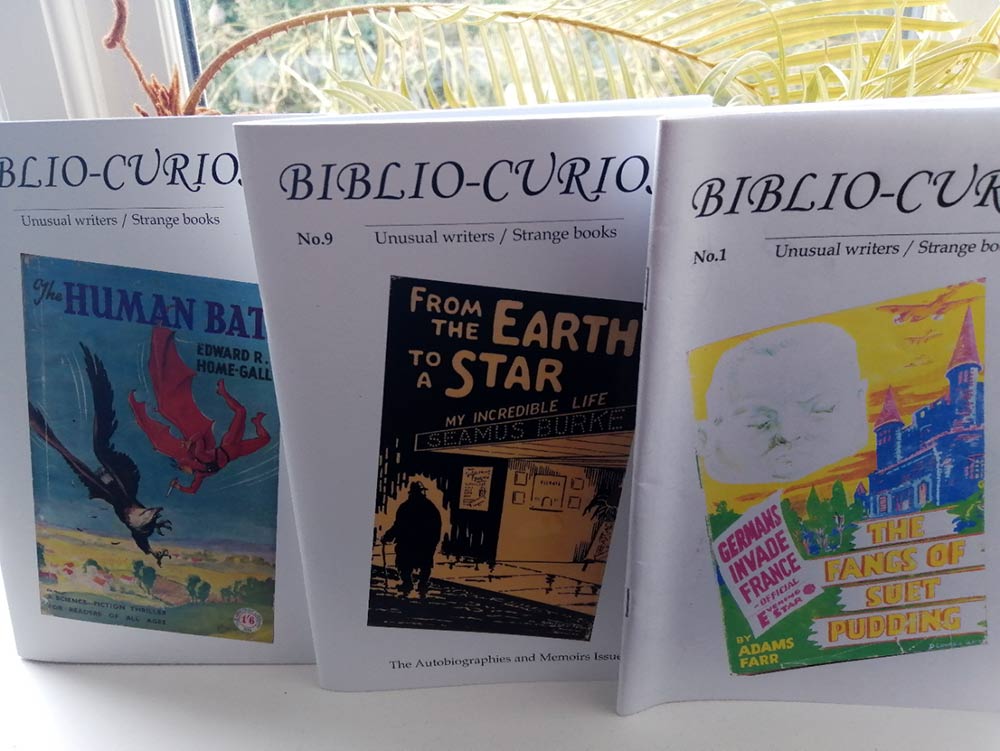

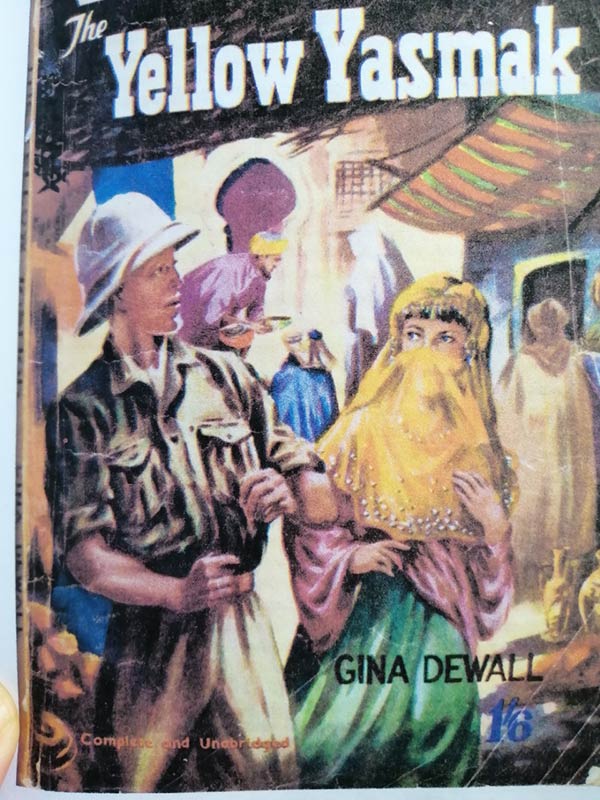

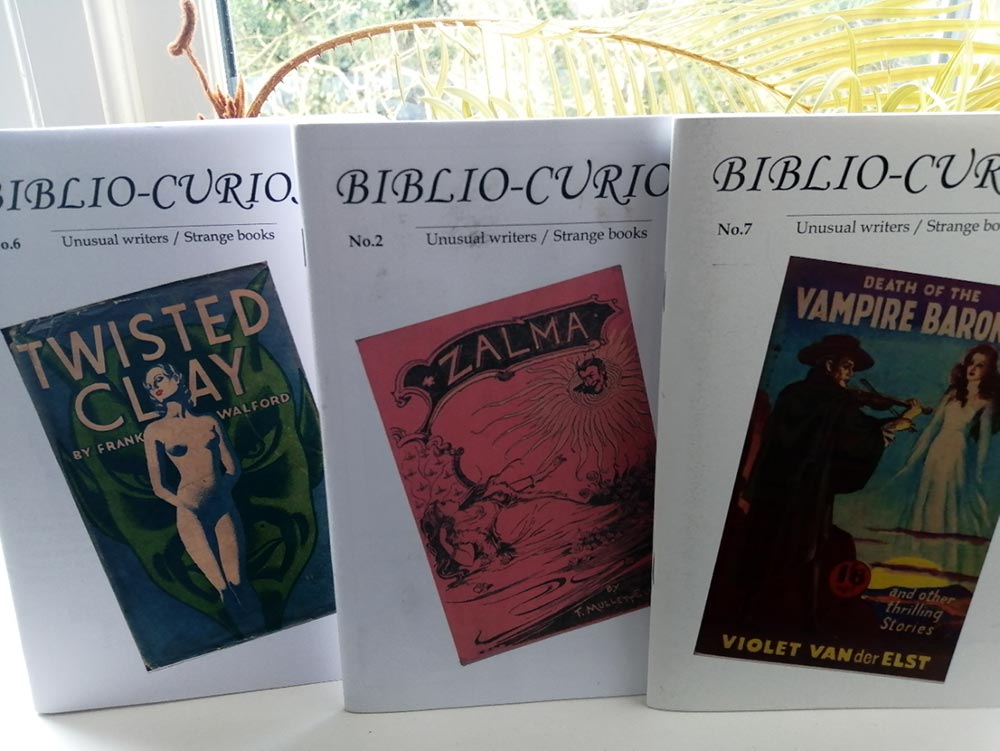

DIY aesthetic is very much part of the world of fanzines, too. Indeed, the above anecdote came to mind in anticipation of an interview with Chris Mikul, writer, publisher and distributor of Biblio-Curiosa. Issue number 9 of his fanzine about unusual writers and strange books had recently popped through my letterbox and I decided it was high time to chat to Chris about it. Chris is a fanzine veteran. He contributed to Donna Kossey’s defunct Book Happy, with which Biblio-Curiosa shares some similarities, and is responsible for the long-running Bizarrism, a fanzine collected into book form by Headpress.

I was surprised to find virtually nothing about Biblio-Curiosa online. I consider it a very good fanzine, full of well-researched and well-written articles about authors and books, all of it fascinating. While I hardly expected it to appear in any of the top ten lists returned in a search for fanzines — that’s not the way the world works — I was surprised by its continued absence the farther I trawled. It didn’t appear in any list, none of them, not even long ones. Nor for that matter did any fanzine that might be construed as edgy or significant in any meaningful way. Instead such lists comprise of vintage punk fanzines that no one can possibly afford, riot grrrl fanzines, art zines (scribbles) and some fanzines that don’t look like fanzines at all. My search for Biblio-Curiosa was contra to our fellow on the aforementioned podcast: here the new had wiped out the old. It was algorithms gone mad.

A picture formed in my head of fanzines in the future. The landscape was that of the 1964 post apocalypse movie, The Last Man on Earth, with Chris Mikul as Vincent Price in the starring role, waking every morning hopeful there might exist somewhere another human being. From one day to the next he makes do, foraging for food and amusing himself. The DIY aesthetic had become a survival skill in this barren future. The other inhabitants of his world, when they do emerge, do so at night. They only appear human. They do not want fanzines.

‘An amusing incident arose from my insatiable liking for custard on almost any kind of sweet. At the serving of dessert a large earthenware mixing bowl brim full of custard was deliberately placed in front of my position at the table as a calculated “funny”. My mother had often said that I would not find a wife willing to make custard every day—in this forecast she was quite wrong.’

E.W. Martell, Some Bods Move On

(E.W. Martell, East Grinstead, 1973)

David Kerekes: The subheading is ‘Unusual Writers/Strange Books’. What is the difference between a title that features in Biblio-Curiosa as opposed to Bizarrism?

Chris Mikul: The short is answer is that Bizarrism is devoted to strange fact, and Biblio-Curiosa to strange fiction. (Although the lives of some of the fiction writers I’ve covered in the latter were pretty strange as well, so the two can blend together.) The main reason I started Biblio-Curiosa was I had a whole slew of eccentric fiction I wanted to read, but as I’m so driven to write I feel mildly guilty if I’m reading a book that’s not for research. So that solved the problem.

These are what might be termed ‘long-form’ reviews, in that you unearth as much about the author as you can, even venturing overseas to pertinent locations. What is it about a book that makes you want to investigate further?

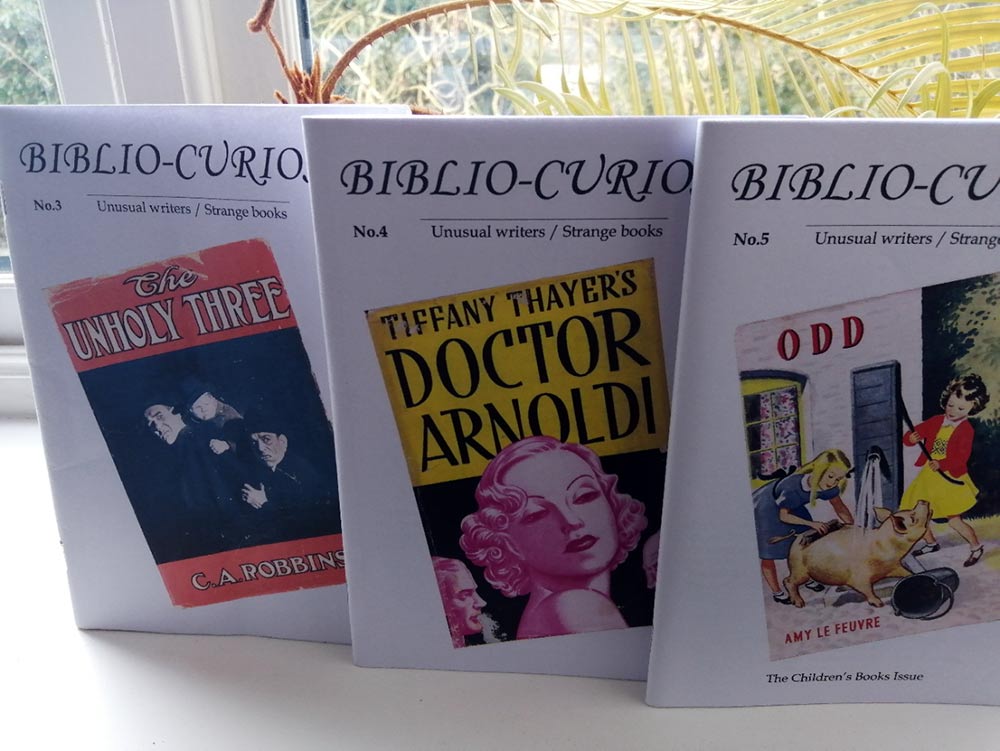

Well, I’ve loved eccentric literature ever since I discovered some collections of William McGonagall’s poems as a teenager, so I’m pretty adept at spotting something that’s going to be up my street. In addition to this, people who write unusual books often have unusual lives, so naturally I want to find out everything I can about them (which, in some cases, has been virtually nothing). I’ve always been fanatical about research, ferreting out everything I can about someone or something. Another thing I like doing is reading the entire output of an author in chronological order. I’m quite a slow reader, for my sins, and some of the authors I’ve covered — such as Tiffany Thayer — were very prolific, so sometimes an article in Biblio-Curiosa can take months to write.

Where do you find the books you review? Are they accidental finds, books you stumble across in second-hand bookshops?

Initially it was stumbling across them in second-hand bookshops. These days, my interest in a writer usually begins with reading a reference to them somewhere — a single line can be enough — then tracking down as many of their books as I can find on the internet.

‘I had found the man they were scouting the country for, but what on earth did I DO?

‘Chuckling, he pulled me across to the far corner of the bed. He pressed something into my hand. It was a dice box.

‘He lifted a corner of the bed-clothes. Something spread in front of me had a strange but familiar pattern. It was a snakes-and-ladders board. Was I going mad, too?’

Adams Farr, The Fangs of Suet Pudding

(Gerald G. Swan, London, 1944)

Is the current situation with Covid-19 likely to affect the way you customarily research and put the zine together? If so, in what way?

No, it hasn’t really affected it at all. I’ve worked from home for years, so that’s nothing new for me. I guess the only thing is I can’t travel to places like [Gabriele] D’Annunzio’s house at the moment.

Many of the books featured are antiquarian, at least 19th century in any case. Was this a golden age of Biblio-Curiosa? What attracts you to this era, as opposed to say modern, self-published books?

I have a particular fondness for the Victorian era, and it’s true that there are quite a few books from the 19th century which would have been seen as conventional when they were first published but seem utterly bonkers now. However, I don’t think there has really been any golden age for the sort or outré stuff I like. These days, there are indeed a lot of self-published books which are self-consciously idiosyncratic (so-called Bizarro fiction), but I usually find these way too calculated. It’s like someone setting out to make a ‘cult movie’ — it can really only happen by accident.

That said, I am personally very fond of the articles you have run on F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre (issue #2) and the Gibbons twins (#1). Both are incredible stories, in which the lives of the authors seem as weird as any fiction. Do you get much feedback to articles such as these?

They’re probably the two articles I’ve received the most feedback on. In the case of MacIntyre, the most interesting response came from Jeff Goodman. I’d first heard from him soon after the article I wrote about Official UFO, the batshit-mad mag he used to edit in the 70s, was included in the first Bizarrism book in 1999. After the MacIntyre article came out, he got in contact again to say he’d been MacIntyre’s best friend during the 70s (of course, I’d had no idea), and he was good enough to write up his recollections of him for my next issue. Jeff’s a terrific guy. Cath and I were lucky enough to have lunch with him in New York last year.

The story of the Gibbons sisters has affected a lot of people, and I’ve had quite a few people write to me asking how they can get a copy of June’s novel The Pepsi Cola Addict. The twins paid a vanity press to publish it in a small edition, and it’s more or less unobtainable. I stumbled on my copy about fifteen years ago (on Amazon, of all places, and priced at a pittance), but I’ve not seen a copy come up for sale since.

Biblio-Curiosa, like Bizarrism, has absolutely no internet presence. Is that a conscious decision, and if so why?

That’s mostly me being contrary. I use the internet all the time (hell, I wouldn’t have most of the books I’ve written about in Biblio-Curiosa without it) but I’m ambivalent about it and the effect on society it’s had. Biblio-Curiosa is all about printed books, so I think it should only exist as a printed artefact. Also, given the arcane nature of the subject matter, I kind of like the idea that people find out about it accidentally after they have seen it reviewed somewhere, then have to seek it out.

You’ve been involved in fanzines for a long time. When did you start? Is there much of a zine scene in Australia?

I published the first issue of Bizarrism at the end of 1986. Prior to that I’d seen a few fanzines about science fiction and so on, but it was a while before I saw anything else that you could call a zine. The zine scene in Australia is actually really healthy. Prior to Covid, there were two large zine fairs in Sydney every year, one in Melbourne and smaller ones in other cities. Hopefully they’ll start up again next year. There’s also a great zine shop in Melbourne called Sticky, unfortunately closed at the moment (like everything else in Melbourne). [Note: Sticky have since opened again.]

What is the Biblio-Curiosa circulation?

I used to print the early issues myself as and when I needed them so I’m not sure how many I sold, but these days I print 200 copies of each issue. It’s always going to be a very niche publication.

What are some of your favourite literary fanzines?

All of Justin Marriott’s publications, including The Paperback Fanatic and The Sleazy Reader — well-researched articles and lots of colour reproductions of lurid paperback covers to marvel at. The long-running Ghosts & Scholars, devoted to supernatural fiction in the manner of M.R. James. Fred Woodworth’s The Mystery & Adventure Series Review documents boy’s adventure stories of yesteryear, which I don’t read — but I love reading about books that I’ll never read. And, although it’s a journal rather than a zine, Wormwood, edited by Mark Valentine and devoted to supernatural and decadent literature.

‘Now werewolves like beautiful women as much as non-werewolves, in fact even more. Waldo proceeded to have his way with Ruth on the mahogany slab where he once lay dead.’

Arthur N. Scarm, The Werewolf vs. Vampire Woman

(Guild-Hartford Publishing Co., Beverly Hills, 1972)

To the aspiring Biblio-Curiosan, what titles would you suggest as the backbone to any book collection — and why?

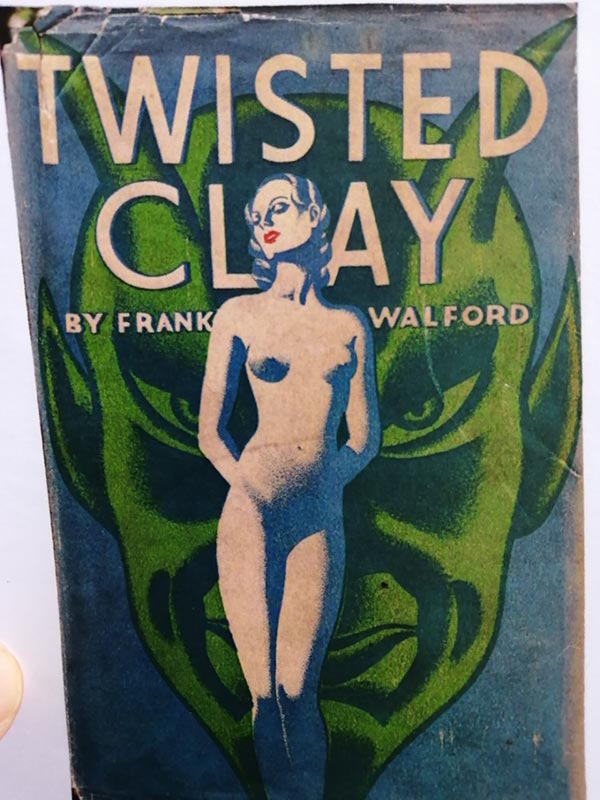

I’d say the cornerstones would be Irene Iddesleigh by Amanda Ros, The Fangs of Suet Pudding by Adams Farr, Twisted Clay by Frank Walford, The Great Boo-Boo by Henry Wilcox, The Queue by Jonathan Barrow, and virtually anything by Harry Stephen Keeler. A paperback or two by Ed Wood Jr also wouldn’t go astray. They’re all quite different, but they all have a unique sensibility and a prose style to wonder at.

I notice that Ramble House is republishing some of these idiosyncratic works. Do you have a close involvement with them?

Yes, I’ve been involved with Ramble House for almost twenty years, and they’ve published two of my books, including my stab at fiction, Tales of the Macabre and Ordinary. All of the Ramble House reprints of books I’ve covered in Biblio-Curiosa have happened because I asked them whether they wanted to do them, they said sure, and I sent them the texts. Then I write an introduction, Gavin O’Keefe does a cover design, and people can read the book again!

How does someone interested in buying a copy of Biblio-Curiosa (or indeed Bizarrism) get in touch?

They can email me at chris.mikul88@gmail.com

-

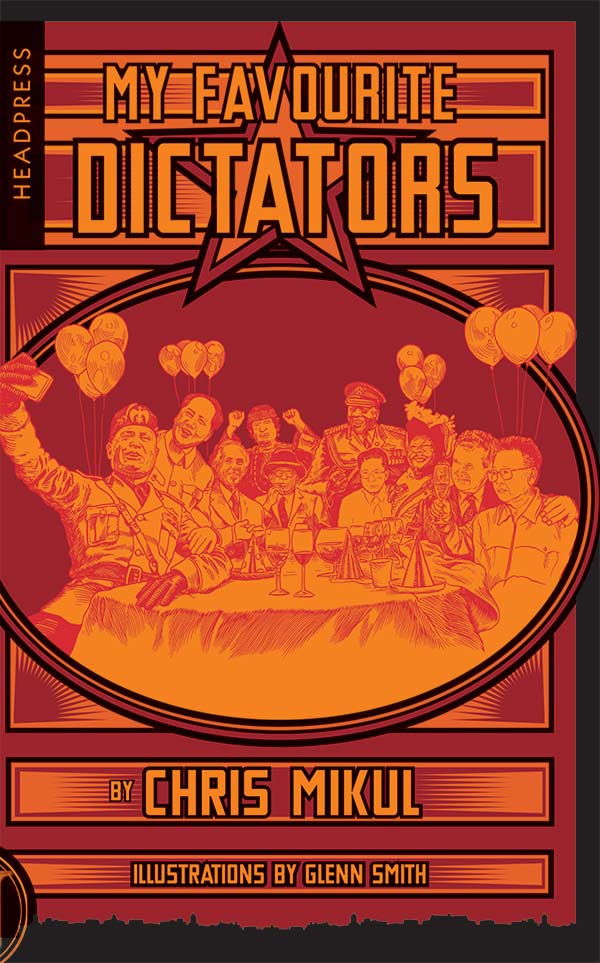

My Favourite Dictators£9.99 – £25.00

My Favourite Dictators£9.99 – £25.00 -

Bizarrism Vol. 2£9.99 – £22.00

Bizarrism Vol. 2£9.99 – £22.00 -

Bizarrism Vol. 1£9.99 – £25.00

Bizarrism Vol. 1£9.99 – £25.00 -

Sale Product on sale

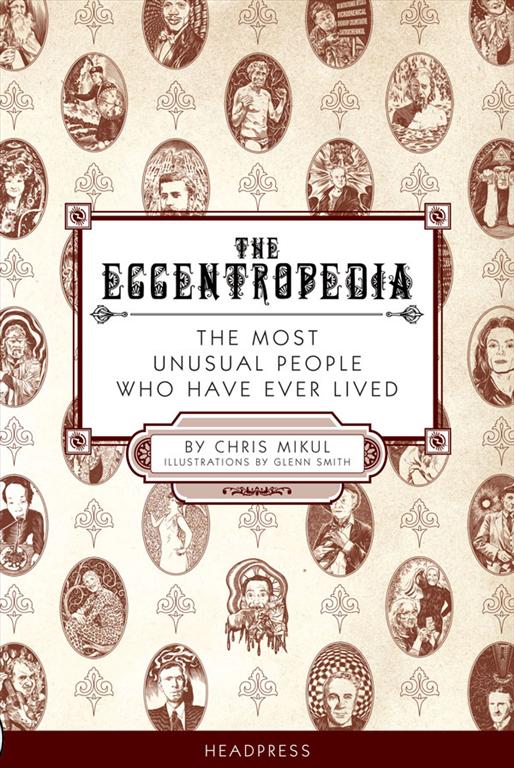

The Eccentropedia£9.99 – £27.00

The Eccentropedia£9.99 – £27.00

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress

One Response