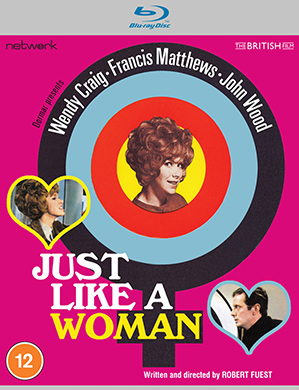

‘As topical as tomorrow’: Robert Fuest’s Just Like a Woman

Just Like a Woman (1966) marked Robert Fuest’s directorial debut. The film follows the fortunes of Scilla (Wendy Craig) and Lewis (Francis Matthews), a couple who work together on a TV variety show and whose marriage is on the rocks. We open on a spectacular row between the two, following which friend John (John Wood) swiftly comes to rescue Scilla from chic suburbia, taking her to his boarding house, a vast pile of Edwardian shabbiness. John’s flat is a curious mixture of Victoriana (military portraits, flags, old penny arcade machines, portraits of Vicky herself) and hints of swinging London. Discussing an upcoming party at the flat, he moans that he’s just had the floor done and warns that he’ll have “no ravers”. John encapsulates the underlying theme of Just Like a Woman that was present in so many other Brit flicks of the 1960s: a society caught between the austerity and Conservatism of the early twentieth century, and the bright lights and pagan promises of the 60s.

Wendy Craig, Just Like A Woman.

Yet, there’s a suggestion that, for all the self-conscious grooviness of John, Lewis, Scilla, and their friends, attitudes towards relationships, gender, and sex have changed little since the turn of the century. A promotional poster on John’s wall proclaims ‘Have Your Meals Here and keep your wife as a pet!’; Lewis is the stereotypical boorish and self-important husband who likes a drink; and Scilla is the long-suffering wife stuck in the middle of it all, yearning for her independence.

Well, everyone has their own ideal of independent life. Scilla’s happens to be having a Futuro-style house built for her by German architect Graff von Fischer (Clive Dunn), “one of the great pre-war eccentrics”. There’s something faintly upsetting about seeing Dunn play a clownish ex-Nazi, not least because he reminded me of Benny Hill’s Fred Scuttle. Sadly, his character is never much developed beyond his Rocky Horror-esque appearance in his bunker office. Other points of interest among the supporting cast are Barry Fantoni as an infuriating hippie musician, and Miriam Karlin as scene-stealing secretary Ellen.

Wendy Craig and Francis Matthews, Just Like A Woman.

The real standout element of this film is its aesthetic sense. Unsurprisingly from the man who would go on to direct The Abominable Dr. Phibes, the sets are lavish, out-there, gorgeous to look at, and brought out beautifully in this newly-restored version. I fear I’m getting a reputation for always going on about the sets of the films I review, but no one could review Just Like a Woman without some swooning over its style. A corporate office boasts a bizarre tableau of garden gnomes and artificial greenery behind the desk. Von Fischer’s headquarters are in an austere factory-like art deco building, but on stepping into his basement-level office we are suddenly in Avengers territory: Scilla’s sunshine yellow coat matches the brightly-painted decor, and in the corner of the room a revolving stage holds a grand piano, pianist, and — inexplicably — a life-size plaster greyhound. A café’s walls are lined top to bottom with aluminium foil. A bathroom showroom is a wonderfully surreal treat, the whole set and scene reminiscent of something from Jacques Tati. The pièce-de-résistance is the house that von Fischer builds for Scilla: a spacecraft-like construction plonked in the middle of a field of cows. Its interior — all split levels and impractical layout — isn’t dissimilar to the Polly Pocket toys for small girls in the 80s that had vertiginous drops between say, a hairdressing studio and a vast bath below. The opening credit sequence and its cut-up/collage style is quintessential British 60s cinema, and a glimpse into its construction is provided in one of the extras, an interview with titles designer Derek Nice.

One of the lavish interiors, Just Like A Woman.

Rather like Robert Hartford-Davis’s The Sandwich Man of the same year, the film is essentially a series of vignettes loosely connected by a central plot (in this case the breakdown of Scilla and Lewis’s relationship). Both films play with the contrast between ‘old’ and ‘new’ London, making for a kind of variety show film that has a bit of something for everyone. There’s a musical interlude provided by American jazz singer Mark Murphy (at that time living in London and playing at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club in Soho), but also a classic bit of comedy farce involving two policemen and a ladies public toilet. Just Like a Woman, though, melds these elements with particularly surrealist effect. Witness, for instance, the row of people in evening dress fishing at the riverside in the twilight, or the final getaway of Scilla and Lewis on a stolen milk float. The trailer (included here as an extra) declared the film to be “as topical as tomorrow” — if only the final decades of the twentieth century had been quite as colourful as this.

Just Like A Woman is released by Network Distributing on 5 July. Order here.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress