Carrying on in the country house: Andrew Sinclair’s Blue Blood

“He’s looking up your dress.” “I’m stepping on his face.”

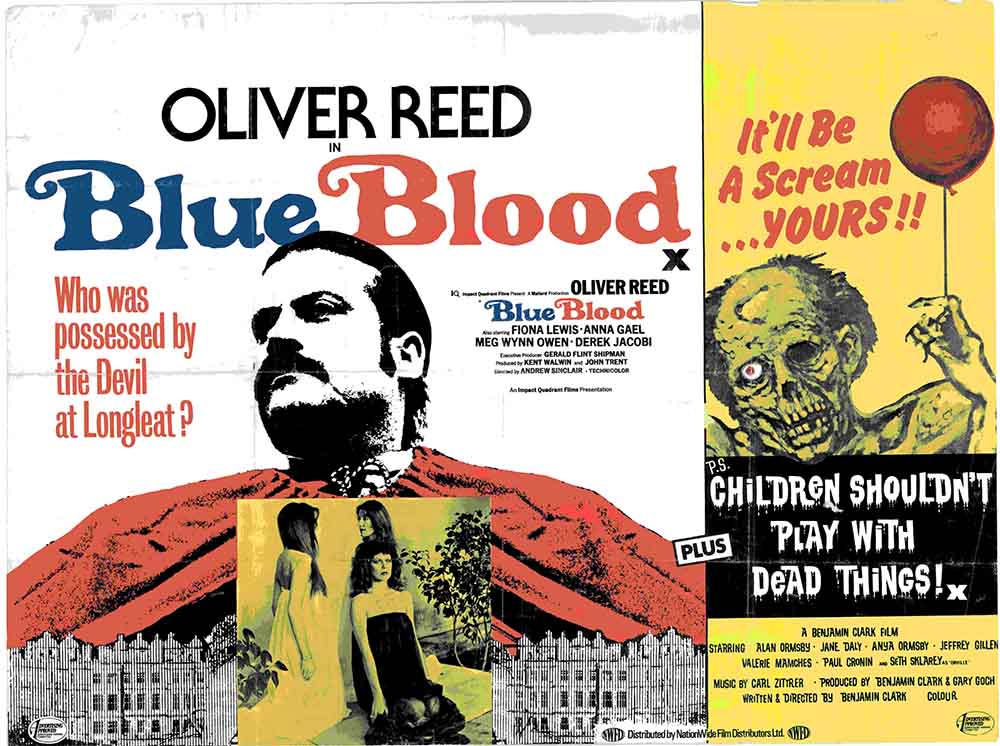

With dialogue like this, you could be forgiven for thinking that Andrew Sinclair’s Blue Blood (1973) is a run of the mill British sexploitation flick replete with mini-skirted mod girls and lashings of hepcat dialogue, but the reality is rather different. Oliver Reed is Tom, butler to Gregory (Derek Jacobi) and reminiscent of a straining pit bull in collar and tie, serving a master who spends an inordinate amount of time desecrating the walls of the family home with childish murals and entertaining his extramarital companions with trips to the on-site safari park.

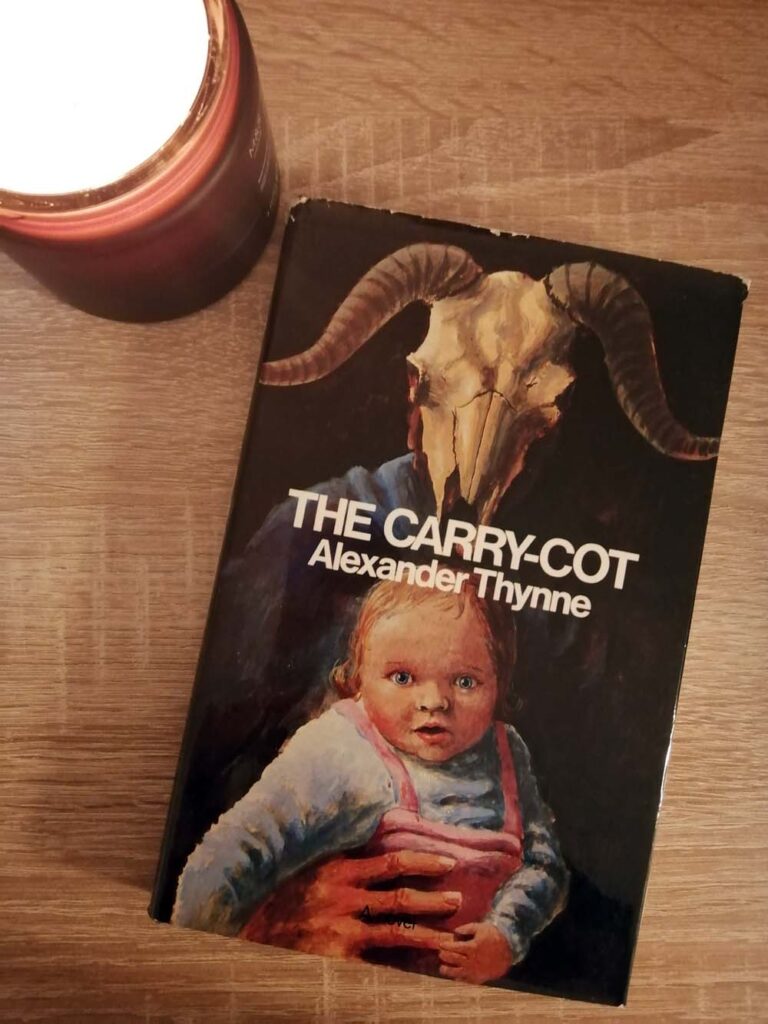

If the vague image of an eccentric, long haired, waistcoated aristocrat pops into your head at this point, give yourself a gold star. Blue Blood is based on 1972 novel The Carry-Cot by the Marquess of Bath, Alexander Thynne (later Thynn), who passed away last year. The Carry-Cot is a slightly rambling tale, more manifesto for polyamory and drug experimentation than anything with a semblance of plot. ‘Why do we have to go around pretending that mankind is monogamous,’ opines Thynne, ‘when the whole of society is copulating like rabbits?’ The Carry-Cot isn’t an obvious choice to translate to the screen, and the difficulty of doing so becomes clear within the first half hour of Blue Blood.

Derek Jacobi, as the thinly disguised Bath character, is a rather unlikeable gent from start to finish. Raising his two young children is “a bore” and on one occasion, having accused nanny Beate of hitting his daughter, he then suggests he might make a clandestine visit to her room in the small hours. Meg Wynn Owen puts in an interesting performance as Beate, hovering between tearful submissiveness and seething anger, whilst Fiona Lewis is her usual effortlessly glamorous self as Gregory’s wife, Lily — a singer whose regular tours allow her husband to employ various replacements in the marriage bed. Carry-Cot author Thynne makes a fleeting appearance as a guest at a party — look out for the gaudy red satin shirt — and another central character is played by Anna Gaël, real-life wife of Thynne. There’s also some light relief in the form of a Mr Humphreys style groundskeeper duo. But the film is stolen by Oliver Reed’s frankly astonishing performance as the slightly camp yet sexually menacing — and somehow inexplicably attractive — Tom.

The Carry-Cot describes Tom as ‘a Jack-of-all-trades’ with ‘a curious blend of cultural influences … half way between hippydom and a caricature of a Dickensian gentlemen’s gentleman,’ sporting tattoos alongside Edwardian trousers and winkle-pickers. Reed’s incarnation as Tom is reasonably true to the book, with slicked down hair and Victorian sideburns, though he succeeds in looking more like an East End heavy than a sixties lovechild. He cuts a massive, hulking presence next to the other cast members, offset by his strange mincing walk and quite ridiculous voice: think a fey English gentleman with a hint of a South African accent. “You know, with a voice like yours,” sniffs Lily, “it’s very difficult to take you seriously.” In the final scenes of the film, as order in the house unravels, it’s almost disappointing to see Reed in his more familiar guise of general dishevelment.

Tom exerts terrific control over the whole household, including Gregory, and throughout the film the suggestion is made that he is involved in something very unpleasant indeed, with occasional crimson-drenched intercuts of Tom in ceremonial robes, surrounded by unclad ladies and a variety of occult paraphernalia. Only very late in the film do we discover that Tom is leading the estate personnel in Satanic rituals, although this development is rather sketchy and not as jarring as it should be. Shot in the same dreamlike red as previous intercuts, the sacrifice sequence could easily be construed as one of Gregory’s acid-induced hallucinations rather than any definitive conclusion. Thankfully director Andrew Sinclair chose not to remain faithful to the book’s description of this climactic scene (although one cannot doubt it would have pleased Reed if he had):

[Tom] cast the cloak from his body. … It was Tom all right: but an intensely phallic Tom, with an erection such as my imagination had never given him credence: painted in vivid colours, and garlanded with a ring of small seashells.

Filling out the sparse plot are shots of the grounds, while the animals of Longleat safari park are credited with lengthy appearances that resemble the stock mondo footage of a low-budget cannibal flick. In one bizarre shot, Tom has a tense exchange with Lily whilst polishing the silver, the lower half of his face completely obscured by a large tea urn. Whether the composition is intended to be artistic, or simply the result of some lax camera work, is open to debate.

When I first wrote about Blue Blood in Offbeat (and from which most of the above is excerpted), I was pretty down on the whole thing. I really wanted to see Peter Cushing as the leisured aristocrat and Christopher Lee as the sinister, charismatic butler, to drive home the relationship between hippy master and Satanic servant. True, The Carry-Cot didn’t offer much to build upon, but watching Blue Blood again now, 11 years later, I’ve softened towards it. Maybe it’s the comforting aspect of those British films that meander and mosey, visually arresting and characterful but not especially plot-driven, like The Sandwich Man (1966) and its literal wandering through London’s streets. Plot (or lack of) aside, whatever happens in the second half of the film is almost irrelevant in any case: by that point the viewer’s attention has fixed inextricably on Reed…

-

Offbeat (Revised & Updated)

British Cinema’s Curiosities, Obscurities and Forgotten Gems

£11.99 – £37.00 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product pageThink you know British cinema? Think again.

Jennifer Wallis

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress