A visit to The Horror Show! A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain

ACT I

The Horror Show!: A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain is a major exhibition that explores horror, not as genre, but an emotional response to modern Britain. Some of the art and objects are forward-looking while others evoke limbo, a provocative backward glance, tooling-up the past, particularly the seventies, as a sort of haunted time zone. It is somehow fitting that the journey to the exhibition begins with disruption, specifically a cancelled train and a diversion to Didcot Parkway where commuters crowd the platform on a freezing December morning. Among them is a man we shall call Eric Norman. He wears spectacles, several layers of clothing beneath his gabardine mac, and shuffles his feet in the sub-zero cold, bashing his gloved hands together to inspire warmth. He does not like other persons on the platform and grumbles at the proximity of so many heavy coats and icy breath-clouds, like a funeral he once attended of a very unpopular man. The diversion isn’t the result of planned rail action but rather signal failure, the first in a series of conniptions designed to disrupt Eric’s otherwise boring day. An announcement over the PA alerts him to the fact that the next train to arrive will be very busy, and not everyone on the platform is likely to fit on board. The news is delivered quickly and lacks sobriety, laments Eric, failing to acknowledge the train is late by forty minutes. Eric shuffles forward on the platform when at last the train appears and rudely gets on board, standing room only, cramped in an aisle where another passenger’s dog, a crossbreed of sorts, tangles its lead around his feet. Too late Eric realises he has boarded the wrong train, that in his haste he has made a commuting error and is headed not to the office but to London. He sighs as he ruffles the dog’s cold ears, the only thing to do in the tiny space afforded him. On arriving at Paddington a half-hour later, he looks for the train that will take him back again but becomes entirely lost in the crowd that swarms onto the escalator down to the Bakerloo Line. Here he gets on another miserable train, and sits in the one available space, between the knees of a young man ensconced deeply in the seat opposite, a slouch of such epic proportions that Eric feels trapped by it. When finally Eric disembarks, unsure where or why, it is midday, and the winter sun melts the ice on the trees of Victoria Embankment Park through which he passes in a daze. He wanders up and down streets, shrouded in the capital’s grey architecture, until at last an intriguing sign beckons: The Horror Show!: A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain. It brings him to Somerset House by the Thames, a neoclassical building that looks like a council chamber, and perhaps once was, with flat, blank walls and big, simple windows. Now, observes Eric, it is an arts centre. He pays the entrance fee and steps into the gloomy interior.

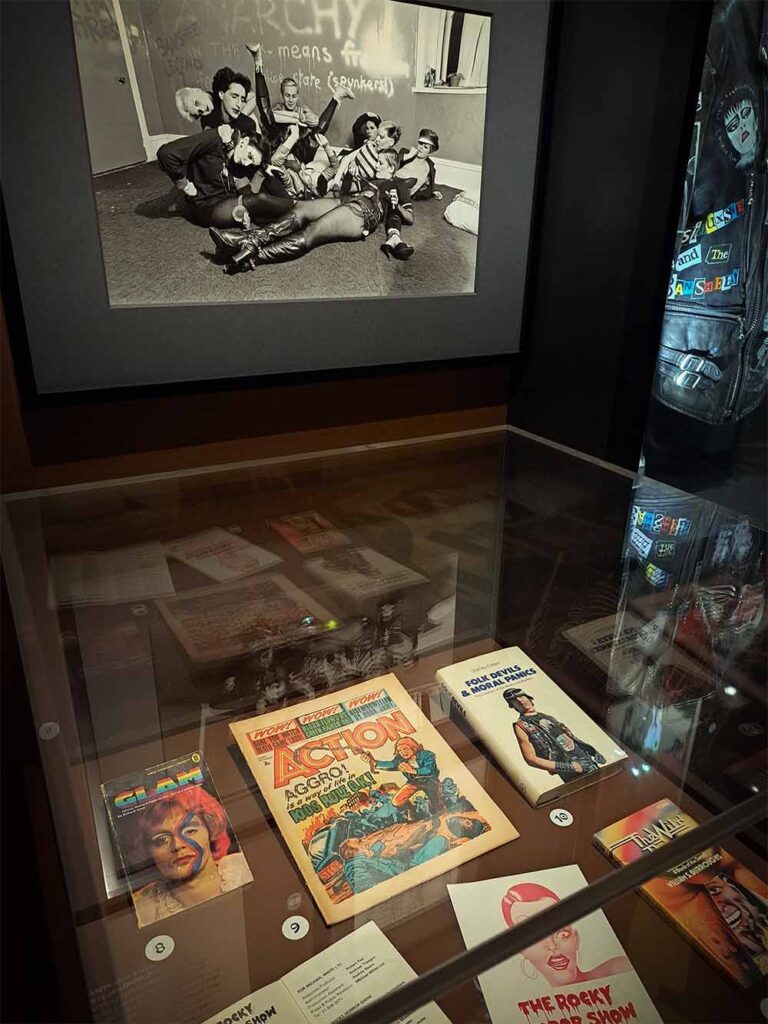

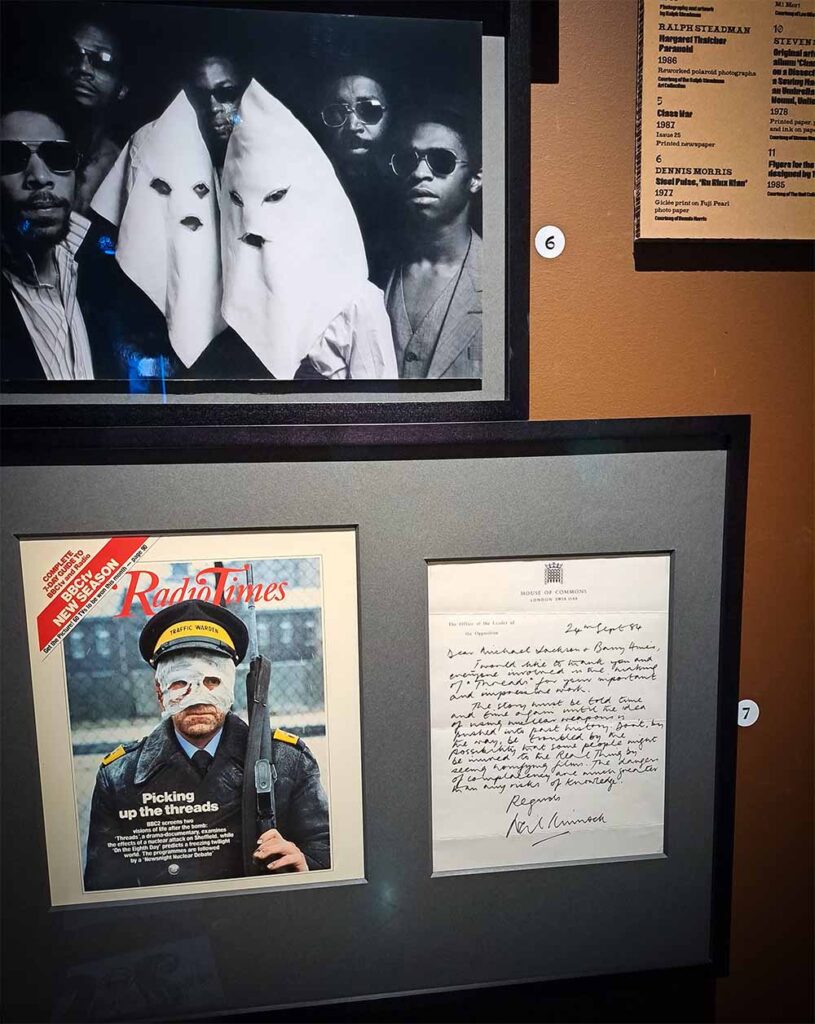

At the start of the exhibition is David Bowie, courtesy of Guy Peellaert’s wraparound cover art for the Diamond Dogs album (1974), which presents the iconic performer as a sideshow freak, half man, half beast, embracing the observer in a knowing, chiselled gaze. This section of the exhibition, identified as its first ‘act’, the 1970s and 1980s, is titled Monster. Political unrest and social division are manifest in a newfound cultural movement, a dimming of the lights as glam rock transmutes into punk rock and births the creative threat of sex and leather. Artefacts of the age include evocative record sleeves, a copy of Britain’s ‘violent’ comic, Action, art and photographs, as well as the Spitting Image puppet of Margaret Thatcher. Alongside these are latter-day interpretations of the age, evoking its spirit in some shape or another. Among them, Jake and Dino Chapmans’ book cover, BANGWALLOP, modelled after the Panther paperback edition of J.G. Ballard’s CRASH, next to which a copy sits.

Eric Norman is familiar with J.G. Ballard, some of his novels at least, not this one. He examines the two book covers, oblivious to other visitors passing by, realising eventually that one is a pastiche of the other. Then a quick glance at the waxed nappa leather bondage mask under glass, and Eric imagines the tired face of his wife Carol behind it. She would never entertain such a notion, which perhaps, he sighs, is the reason why the idea came to mind in the first place. He wanders back to the lithograph of David Bowie, the Diamond Dogs artwork, and considers it anew, knowing now that one thing begats another, that The Horror Show! is an exhibition of reactionary ideas, that he is being invited to engage with the exhibits in a way that perhaps he hadn’t when last he visited the British Museum and stared at a brass head of an Ooni of Ife, a king. He had nodded referentially at the brass head, simply one ancient artefact among many, and moved on. It spoke little to him of his life. What of David Bowie? Eric never really cared for him either. As a teenager and old enough to recognise a good tune, the showboating got in the way for Eric, which is why he much prefers Bachman-Turner Overdrive to The Clash.

ACT II

The second act in the exhibition is Ghost, the 1990s and early 2000s, constructed around a collapsing global economy and the dawn of the Internet. Visually this is the most compelling aspect of The Horror Show!, and its most disorientating. David Shrigley’s I’m Dead (2007) is a taxidermy kitten holding a sign that reads ‘I’m Dead’. Graham Dolphin’s Door (Joy Division Version) (2012) is a white-painted wooden door covered with scratched epithets to Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis. Another door, off white, this one by Kerry Stewart, has a frosted glass pane that reveals on the other side a charity collection box boy, the type once found on every high street. It’s called — great title — The Boy from the Chemist is Here to See You (1993). These convey an anxious impression. Elsewhere, a collection of pieces constitutes a hauntological conundrum: a 2007 mixtape compiled by writer and cultural theorist Mark Fisher, which he has titled ‘Hauntology 1’ (on it, Residents, BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Coil, and others), plus examples of product from Scarfolk and the record label Ghostbox, respectively posters that are near-perfect simulacra of 1970s government issue health and safety warnings, and music that evokes time and place more than it does a ‘good tune’. Hauntology is worthy of further discussion. It has moved from high concept into homage/pastiche, with a preoccupation with the 1970s. The artists and satirists who create it belong to a ‘ghost’ era, and like ghosts invent a past that almost never happened.

“Because it has always already begun, representation therefore has no end. But one can conceive of the closure of that which is without end.”

— Jacques Derrida[1]

Arguably this aspect of the exhibition threatens to overtake it, new works looking like old works. Hauntology is a form of blob and nearly impossible to contain, a paradox that William Burns, in his forthcoming Ghost of an Idea: Hauntology, Folk Horror, and the Spectre of Nostalgia, is concerned about. ‘[H]auntology itself has become a ghost, a nostalgic, spent force merely haunting pop culture and academia as a hip term to drop, no longer a vital critical field of inquiry, but, rather, a fading phantom.’[2]

Eric Norman continues his trip through The Horror Show! He is looking at a life size dummy that purports to be a self-portrait of the artist as a drowned man. He re-reads the accompanying notice: ‘Jeremy Millar: Self-Portrait as a Drowned Man (The Willows) (2011).’ It’s grotesque. There are no further clues. He likes a series of Polaroid photographs by Adam Scovell, recognising the names of several of the subjects attached to them. MR James, his childhood home captured in one print, and WG Sebald, his grave in Framingham Earl, Norfolk, captured in another. There is also a Polaroid of a place called Bix Bottom as seen in the 1971 film, The Blood on Satan’s Claw. Eric hasn’t seen that film since before he married Carol. It conjures a memory. We leave the exhibition momentarily for Eric’s own past.

The television schedule on the night of Halloween 1997 had piqued his interest, beginning with a documentary on the supernatural followed later by the horror film, Blood on Satan’s Claw. One of the young witches in the film took her kit off, and Eric plugged in the dial-up modem and logged onto the family computer, eager to discover more. An online search for the nude actress lent itself to another search and then another until at last, at around midnight, he arrived at a nugget of truth, a bulletin board dedicated to witchcraft and the pagan lifestyle.

He met the witches online.

He joined the forum and was welcomed as a ‘young mage’ by witch-people with exotic names, such as Tade Blackwood, Sabine Wolfmoon, Agatha Harkness and Amelia.

Witches don’t sleep on All Hallows’ Eve, wrote Agatha Harkness when pressed on the lateness of the hour.

There are a couple of rooms in this act that offer an immersive audio-visual experience. One of them, An Undimmed Aura by Laura Grace Ford, is like being in a council estate on the edge of the industrial estate near to where Eric grew up. It might still there. It was a vibrant if unsafe place, but located in this room, surrounded by black and white photograph blow-ups of urban landscapes, the environment is uncommonly tranquil — not at all like that time a gobby lad shouted at him from a window on a block of flats, and he shouted back expecting a fight, then ran away. Eric finds sanctuary in the room, the threat of violence a poem. Later he examines some of the props used in the BBC fictional documentary Ghostwatch (1992), including a floorplan of the location house where the manufactured spook materialised. The final act in The Horror Show is Witch.

Eric had followed some chat on the bulletin board about the Rollright Stones, which sounded to him a lot like The Rolling Stones, and also preparations for the winter solstice. Agatha Harkness explained in one message that on the winter solstice there is dancing and singing in the dark and men and women in robes. Like in that film? asked Eric. Like in that film, came her enticing reply. After several weeks of correspondence he was invited to a meet-up at a pub

So, Eric arrived at the Swan and Castle, eager and early, and considered writing a sign that alerted the group to the table he had commandeered. But what would a sign say that didn’t attract undue attention? Witches Meet-Up? He dismissed the idea, expecting he would recognise the members of the group when they arrived in any case: The men who were wizards would probably look like wizards, and the women who were witches would look like witches, spinning spells from long fingers. They arrived instead as ordinary people, nothing to set them apart except for an occasional pendant — he counted three — and one pair of novelty contact lenses worn by Tade Blackwood, whose name was Jill. Only half the people who said they would come had bothered to show up, most of them women, which was fine, none of them as spooky or as flirtatious as suggested by their online avatars, which was a disappointment. Sabine Blackwood presented her new tattoo, still raw around the edges, and the evening then settled into quickening rounds of drinks and conversations between parties across the table. Concerns were voiced about shelving units and Leamington Spa when one person — he wore a colourful hat and had brought along his mother — turned to Eric to ask what path he followed. Eric didn’t understand the question. “What paths do you mean exactly?” he replied.

On his way home that night in the drizzling rain, Eric, hungover, observed a leaf fall from a tree behind St Kenhelm church, illuminated by a fuzzy yellow streetlight. The leaf twisted and danced before it settled at his feet, among other leaves in a mulch that smelled of dead toads.

The witches had spoken of a dawn meeting at the ruins of Minster Lovell Hall, celebrating something to which he was invited. This, perhaps, was a sign and Eric couldn’t wait.

ACT III

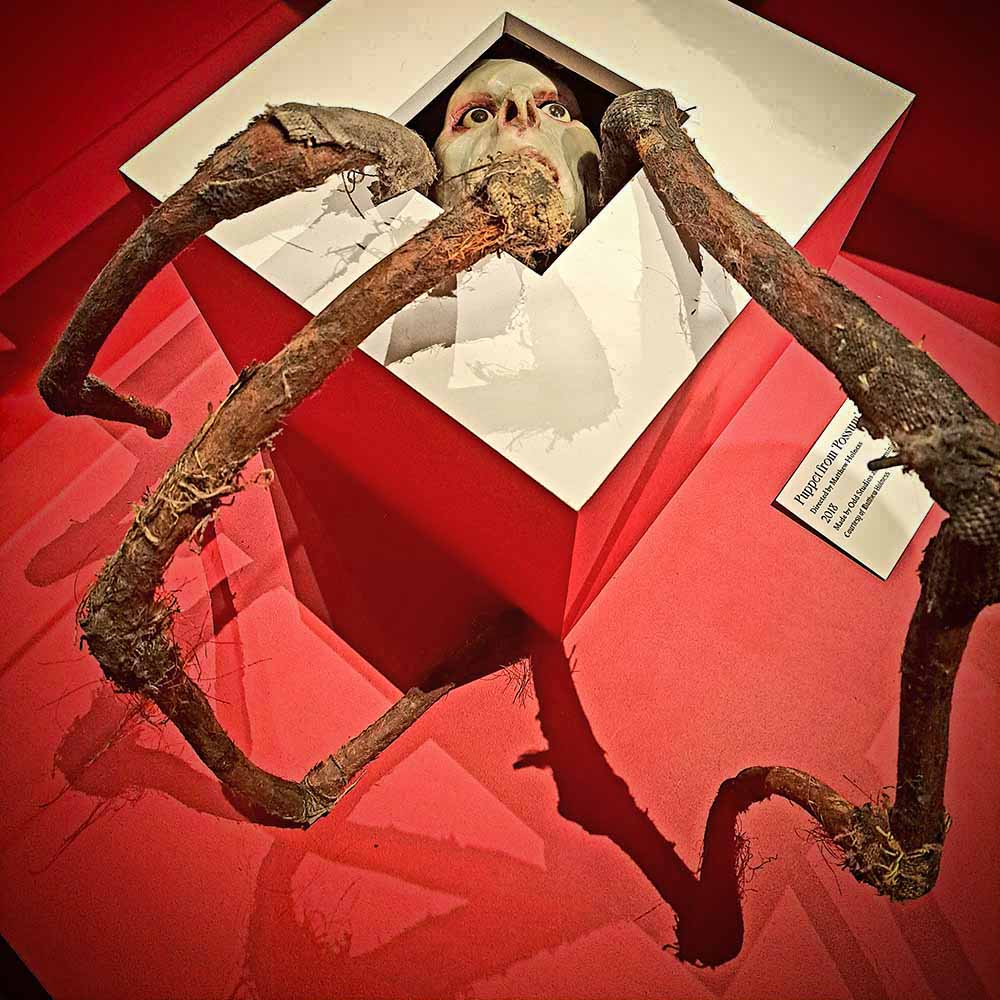

The final act in The Horror Show! picks up the financial crash of 2007 and continues through to the present. The emphasis is on a new sorcery in an ‘accelerated and hyper-mediated topography’[3], running counter to neoliberalism. Suzanne Treister’s tarot deck sums things up clearly, cartomancy as a call to arms, inciting anarchism and an end to industrial civilisation — Hexen 2.0 Tarot (2009-11). The Major Arcana is present in a more traditional, equally beautiful fashion, courtesy of Sophy Hollington’s Linoleum Blocks (Inked) (2018). Wax fingers, mannequin hand, theatrical blood and a trick stage knife are some of the props that represent Marisa Carnesky’s performance piece, The Incredible Beeding Woman (2016–19). Charlotte Colbert has a Cellular Amulet (2021), a painted bronze sculpture that resembles a biological atom, and, like all organisms magnified, it conveys a sense of entropy and otherworldliness. There are references to movies, too. A wicker mask from Ben Wheatley’s Kill List (2011) as well as behind the scenes photographs from Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973). These particularly unsettling representations of paganism and magick, tellingly films, both have at their core troubled males, at odds with the general composition of Witch, otherwise a brightly lit space, mostly feminine and mostly celebratory.

The witches did not come. Eric waited for hours, having cycled all the way from home, and watched the sun rise over Minster Lovell alone. They each had a reason, the witches, he later discovered. Car trouble and the flu and a barrel of excuses. Thought Eric, sitting on damp grass beneath a spoiled wall of the old Manor House, black against the dawn: They sit around in pubs, stipulating on what day and at what time they can and cannot travel before arriving at a mutually acceptable conclusion, and still the witches do not come. He was not so inclined to accommodate the witches after that, because chances were they would not turn up anyway. Shortly before he quit the group, Agatha Harkness attached a picture by Dutch artist MC Escher to one of her messages, the sort of thing she would often do. When Eric stumbled on a print of the same picture in the Athena poster shop weeks later, he was compelled to buy it.

The end of the exhibition. Exiting the gift shop onto the Embankment, the opposite side of the building to the seasonal skate rink, there is a façade built onto an archway that consists of large, bulging eyes, a pig’s snout and fangs. To quizzical tourists it must appear as if, behind this wall, through this archway, there is a ghost train waiting. Ghost trains do not need to make sense. The exhibition catalogue states that The Horror Show! is impressionistic, ‘remnants of an archaeological dig into Britain’s cultural psyche’.[4] It comprises talismanic relics and is filled with wonderful, distant echoes. But — the ubiquitous but — there is a significant omission. There is no reference to the literary counterculture that sprang out of the ‘video nasties’ panic and the Video Recordings Act 1984, an age of techno-terror and moral outrage in which some unremarkable horror films and the viewing of them was seen by many as the manifestation of evil. This spilled into police raids, fines, imprisonment, and soon enough a collector’s market for said films, a network from which evolved a ‘scene’ — not a scene driven by music or youth culture but by the underground itself. More than thirty British exploitation film and ‘gore’ zines were published in 1993.[5] Manchester-based zine Headpress was one aspect of this creative backlash, among the many DIY endeavours that sought to chronicle the post ‘nasties’ era, the substrata anxieties, modelling new apocrypha out of the scar tissue. An ‘exploration of the more bizarre and deviant aspects of modern culture,’[6] what the mainstream liked to call ‘transgressive’, it included art, articles and thought pieces, some on and by artists that feature in this exhibition. The masthead on its first issue in 1991 was ‘Sex Religion Death’, a catch-all designation for — what?

Arriving home, Eric finds Carol watching highlights from last night’s Love Island. She asks from the settee how his day was, and he responds in good humour with a kiss on her cheek, but no mention of his trip to London, no mention of The Horror Show! When he takes off his coat, hanging it in the hall by the front door, he hesitates for a moment at the framed picture above the radiator. It’s a numbered print of an MC Escher drawing, hanging for as long as he cares to remember in the hallway because, insists Carol, it’s drab. It’s called Relativity (1953) and features three separate worlds built into one, a typical Escher conundrum, inhabited by figures and a common stairwell. But the structure is such that while the inhabitants may pass one another on the stairs, they can never meet, and there is no clear up or down. The best vantage point, determines Eric, looking close into the picture, is the hallway, specifically the spot on which he stands.

Notes

[1] Cited in William Burns, Ghost of an Idea: Hauntology, Folk Horror, and the Spectre of Nostalgia. Forthcoming, Headpress.

[2] William Burns, Ghost of an Idea: Hauntology, Folk Horror, and the Spectre of Nostalgia. Forthcoming, Headpress.

[3] Claire Catteral, ‘Welcome to The Horror Show!’ The Horror Show! A Twisted Tale of Modern Britain in Three Acts. London: Somerset House (2002), p.6

[4] ibid.

[5] Ray Stewart, ‘Fanzine Directory 1993’, Magazine of the Movies 1993–94 Yearbook, p.48

[6] Author not credited. ‘Outrageous contagious’, Back Brain Recluse No 20, Spring 1992, p.21.

Exhibition photos taken by David Kerekes.

Co-curated by Iain Forsyth & Jane Pollard and Claire Catterall

- Event Report

- 1970s, Adam Scovell, Bachman-Turner Overdrive, BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Ben Wheatley, Charlotte Colbert, Coil, David Bowie, David Shrigley, Diamond Dogs, Ghost of an Idea, Ghostbox, Graham Dolphin, Guy Peellaert, Ian Curtis, Jacques Derrida, Jake and Dino Chapman, Jeremy Millar, JG Ballard, Joy Division, Kerry Stewart, Kill List, Laura Grace Ford, Love Island, Margaret Thatcher, Marisa Carnesky, Mark Fisher, MC Escher, MR James, Residents, Robin Hardy, Scarfolk, Somerset House, Spitting Image, Suzanne Treister, The Blood on Satan’s Claw, The Clash, The Horror Show! David Kerekes, The Wicker Man, Top of the Pops, video nasties, William Burns, witchcraft

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress