“Everything has been here for ages” Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii

Pompeii and Pink Floyd

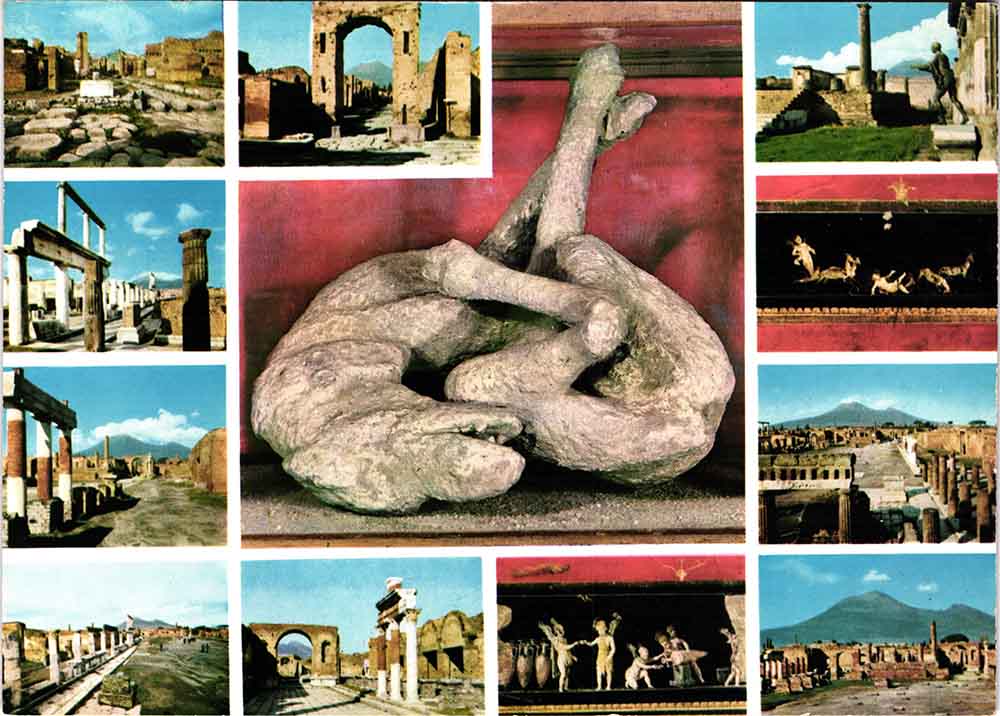

The Roman city of Pompeii is in the Campania region of Italy, 23km south of Naples. Today it is a one-of-a-kind archaeological park. Each year millions of tourists visit the city that was destroyed in an instant by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79CE. Pompeii, its streets, buildings, and even some inhabitants, remain remarkably well-preserved, dormant for centuries beneath ash and debris, trapped for eternity in a violent moment. In 1971, Pompeii was the unlikely location for a performance by the experimental rock band, Pink Floyd. The concert, documented on film, took place in the amphitheatre on the eastern edge of the city, and much like the doomed city itself, seems to resonate out of time. Pompeii is a chimeral place, and the concert venue was once the location of gladiatorial contests and fights to the death. The amphitheatre once held the 2,000 inhabitants of the former city, and yet Pink Floyd played to no one. There was no audience beyond the sound and film crew. They showcased several new songs and a couple of old ones beneath a blazing sun, and into the night. The result might easily have been an insignificant performance dominated by landscape, a curious attempt by a rock band to inveigle its own inflated sense of purpose through association. But the concert is not that.

Formed in London in the early 1960s, the proto-Pink Floyd was a rhythm and blues band. Its members — which would include, in time, Nick Mason, Roger Waters, Richard Wright, Syd Barrett and David Gilmour — were students of architecture and art. In the mid sixties, they would become the spearhead for the new music of a London transmuting into a summer of love. From the outset, Pink Floyd preferred ‘happenings’ to traditional concerts. They never wanted to be a band that people could simply ‘jig about to’,[i] but rather one that shared an audio-visual experience with the audience. Nigel Fountain describes a band that, in 1966, ‘specialized in serious experimentation in sound and light, wore white coats, and would discuss their work, post-performance, with the equally serious audience’.[ii] Pink Floyd’s Games For May at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on 12 May 1967 was an improvised showcase for the forthcoming debut album, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, with the band chopping wood on stage and ruining furniture, which resulted in a ban on them ever performing there again. It was performance that shaped Pink Floyd. The light-shows and kaleidoscopic environment of clubs like UFO and Middle Earth inspired them ‘to abstract and stretch out their instrumental sound’.[iii] To the public eye, Pink Floyd appeared to be a band in transition, alternating between pop whimsy and brooding avant-garde dirges, as evidenced in archive footage from Top of the Pops and countercultural artefacts such as Tonite Lets All Make Love In London (1967). When frontman Syd Barrett left the band in 1968, the tea-and-cake psychedelia went with him. It would have looked ridiculous if the band that played at Pompeii several years later wore the paisley outfits and bacchanalian smiles of their former selves. The band at Pompeii is worthy, tonally and visually a lot like the excavated city itself.

On the soundtrack the swell of a heartbeat

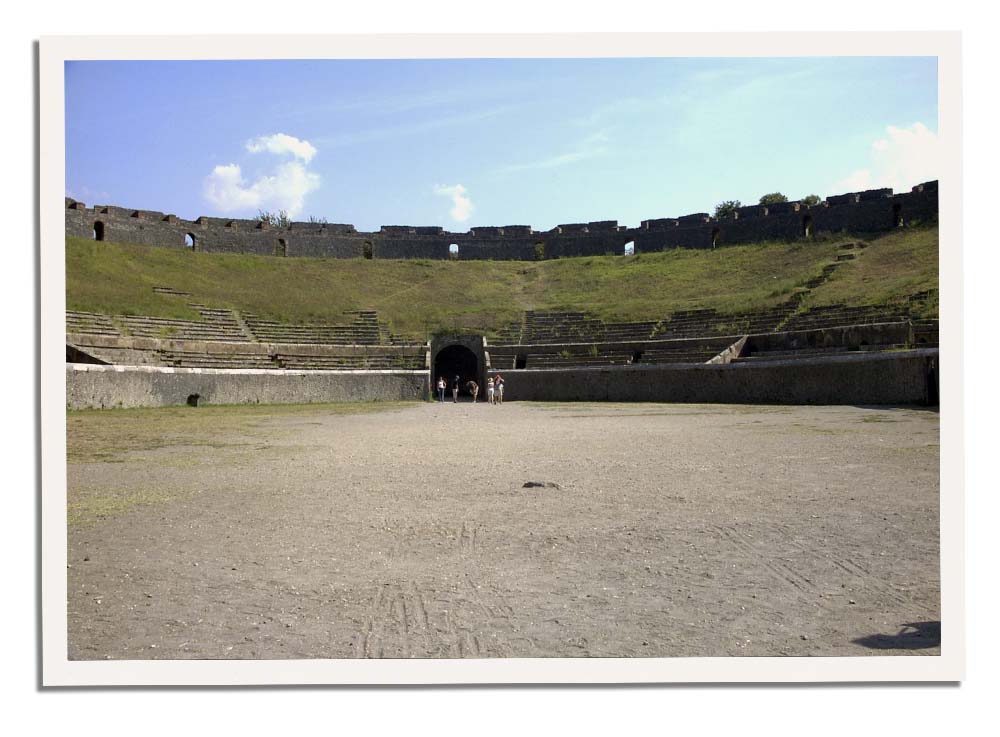

Directed by Adrian Maben, Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii (1971) opens with a wide shot of the amphitheatre: oval, with a bank of stone seats largely covered in vegetation, and in the clear blue sky in the distance is Vesuvius. Figures arrive in the dusty arena. Too far away to see them clearly, these bring instruments (first a gong), and then film and sound equipment. On the soundtrack the swell of a heartbeat and the rumble of symbols emerge. The scene is inter-cut with the title and opening credits, cutaways that act as a kind of time-lapse for the construction taking place. More equipment has arrived. A flatbed truck drives across the dusty arena floor. Finally, the speakers are in place, a black stack that cuts a line across the arena (directed away from Vesuvius).

Shot with a static camera, the prologue establishes the unusual vista and our place in it as viewers. There is no emotional investment, the distancing long shot doesn’t allow it, and yet the images are loaded with purpose and meaning. The vantage point and forced perspective of this opening shot make the arena look like the sheela-na-gig, the figurative stone carving found on churches in Europe in which female genitalia is exaggerated and exposed. There was no shortage of brothels in Pompeii, and recognition of fertility gods can be witnessed in the ‘stanze proibite’ (closed rooms) of the Museum of Naples.[iv] Whether intentional on Maben’s part, the visual does connote the hidden dimensions of the landscape and the ritual unfolding. The enigmatic city, the slow panning shots, the carefully considered movement of the band and the sound they make is at once sexual, pagan and talismanic.

Everything is scenery

‘Echoes part 1’ is the first track the band perform in the film. During the song’s ethereal introduction, we return to the vantage point at the start of the film except now a long tracking shot brings us slowly into the arena, where the band is playing. Also present is the crew. At first, it appears as if this is a still shot, and everything has been here for ages, waiting. As ‘Echoes’ hits its stride, another tracking shot shows the back of the band, the back of the speaker cabinets and the crew filming them. It’s a majestic sequence, one that puts us slap in the middle of things. Amid all this technology is a dusty floor, earth, loose rocks surrounded by the walls of the amphitheatre. Somewhere the sky. The stencilled inscription on the reverse of the speaker cabinets reads ‘Pink Floyd London’. Everything here is scenery, obscured in time and place.

Maben had yet to direct a film when he first approached the band in 1970. Nothing came of his initial idea to make a film that married the music of Pink Floyd with classic and contemporary art. A couple of years later, he was inspired to try again after visiting Pompeii on holiday. According to Maben, he got the idea for Live At Pompeii when he returned to the amphitheatre at night in search of a lost passport. Maben didn’t want a conventional rock film in the tradition of Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock (1970), which inter-cut a band’s performance with the reaction of an audience. Nor did he see any point in following D.A. Pennebaker, and the reportage style utilised on the Dylan tour film, Dont Look Back (1967). Instead, Maben envisaged Pompeii as an antithesis to the conventional rock film. The main idea, he says, was ‘an anti-Woodstock film where there would be nobody present. The music and the silence and the empty amphitheatre would mean as much, if not more, than a million crowd.’[v]

The marriage of art and music

It’s not difficult to see how Pompeii might have appealed to a band that Mick Farren has described as taking ‘an almost diametrically opposed position’ to that cultivated by many rock stars.[vi] But the band was also, at this point, desperate to break into the US album charts and thought a film might help. They had toured extensively and acquired a Stateside following, yet the US charts eluded them. This said, it remains a conundrum that no official live album followed the film. The tracks for Live At Pompeii comprised mostly new material, and the band was evidently happy with their work. The film is not linear, but jumps backwards and forwards between night and day. I would say that Maben’s original concept of marrying Pink Floyd with art is not completely absent. In ‘Set The Controls For The Heart Of The Sun’, one gets a sense of what he may have intended for his unrealised idea, with cutaways to Pompeiian statues and art fitting well with the song. But a marriage of art and music is not unique (Ken Russell’s early career in television comes to mind), nor is a band playing in an empty auditorium. Indeed, Pink Floyd performed such a gig once before, in Hour with Pink Floyd, a live special filmed by public television station KQED and first broadcast in January 1971.[vii] But while empty, the location in this instance is hardly important:

the San Francisco Fillmore Auditorium is in total darkness, and the band might just as well be playing in a small back room.

The landscape of Live At Pompeii remains unique. It is an ancient arena, buzzing with a lost metropolis, and yet here is Pink Floyd in the middle of it, skinny men where gladiators once were. I am reminded of a comment on architectural art by Philip Wilkinson, who compares a rough pencil sketch with a hard- edged technical drawing. The difference, says Wilkinson, is one of aesthetic beauty in that sketches ‘force us to look closely before they reveal their secrets.’[viii] Live At Pompeii is a lot like this. The film, which runs a little over an hour, satisfyingly combines the old and the new, ancient Pompeii and Pink Floyd. The only lighting effect is the natural hue of the October sun. Having visited Pompeii several times over the years, it is not possible for me to view Live At Pompeii entirely removed from these visits. I have memories of the places seen in the film, of standing in the amphitheatre and walking through the paved city streets and hopping along its stepping stones. However, I have always managed to schedule these visits at the height of summer when the heat becomes unbearable. In all my visits, I have never travelled far, and so Pompeii for me is unfinished, with Live At Pompeii becoming a sort of imaginary route-map.

Several bootlegs exist

As noted, there is no official album to accompany the film. (Several bootlegs exist.) The songs were recorded live at 24-track quality and were equal to, if not better than, any studio recording, according to road manager Peter Watts.[ix] Once a track was laid down, the band would huddle together to listen to it on headphones. In these moments in the timeless arena, Maben says, ‘You could hear a pin drop.’ In recent years, this material has been included in box sets of rare and unreleased Pink Floyd.[x] It remains a peculiar oversight that no soundtrack of Live At Pompeii has ever seen the light of day and yet also fitting. The power of this recording is the landscape on which it sits. This is not something for people to jig about to, but rather a liminal space.

Pink Floyd was never the same after Pompeii. Round the corner was the international best- selling album, The Dark Side Of The Moon, and then came gigs that were less like happenings and more like spectacle. They never sounded this good again, either. ‘[S]ound is a haunting, a ghost, a presence where location in space is ambiguous and whose existence in time is transitory,’[xi] says David Toop, and Pink Floyd at Pompeii is very much in keeping with this hypothesis. Recent attempts to revisit Pompeii by director Maben and former Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour totally miss the point. Maben’s 2001 Director’s Cut of Live At Pompeii adds footage of rockets taking off and space vistas. It also includes archive material of the band at work in the studio (on another project), beefing up the running time of the 1973 theatrical cut. It’s a mess. Gilmour, meanwhile, as part of a 2015-16 solo world tour, returned to the ancient city, from which came his own film as well as a live album. The amphitheatre in this instance was filled with an audience dazzled by pyrotechnics, and the landscape is rendered insignificant, buried at last.

Notes

[i] Roger Waters speaking on BBC2’s The Look of the Week, broadcast 14 May 1967. www.youtube. com/watch?v=Cfy1rCKI0x8.

[ii] Nigel Fountain, Underground: The London Alternative Press 1966–74 (Routledge, 1988), p.24.

[iii] Rob Young, Electric Eden: Unearthing Britain’s Visionary Music (Faber and Faber, 2010), p.464.

[iv] Michele D’Avino, Pompeii prohibited: Sacred, augural and customary eroticism in the ancient city buried by Vesuvio (Procaccini s.d., 1993).

[v] All quotes by Adrian Maben taken from Interview with Adrian Maben, Director of Live At Pompeii. Dir: Storm Thorgerson, undated. Extra on the DVD, Pink Floyd Live At Pompeii, The Director’s Cut. 2003.

[vi] Mick Farren, Elvis Died for Somebody’s Sins But Not Mine (Headpress, 2012), p.97.

[vii] Josh Jones, ‘Pink Floyd Films a Concert in an Empty Auditorium’, Open Culture (2020), www. openculture.com/2020/01/pink-floyd-films-a-concert-in-an-empty-auditorium.html. Last accessed 23 Sept. 2022.

[viii] Philip Wilkinson, Phantom Architecture: The fantastical structures the world’s great architects really wanted to build (Simon & Schuster, 2017), p.10.

[ix] Peter Watts quoted by Adrian Maben. Interview with Adrian Maben, Director of Live At Pompeii.

[x] The lavish twenty-seven-disc collection, The Early Years 1965–72, was released in 2016 and includes a remix of the Pompeii audio as well as KQED San Francisco’s Hour With Pink Floyd. The more affordable 2017 box, Obfusc/ation 1972, also includes the Pompeii audio.

[xi] David Toop, Sinister Resonance: The Mediumship of the Listener (Continuum, 2011), p.xv.

-

Gathering of the Tribe: Sex“Love is two minutes and fifty-two seconds of squelching noises” —Johnny Rotten, Rolling Stone£0.00

Gathering of the Tribe: Sex“Love is two minutes and fifty-two seconds of squelching noises” —Johnny Rotten, Rolling Stone£0.00 -

Gathering of the Tribe: RitualVol 3 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £12.99

Gathering of the Tribe: RitualVol 3 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £12.99 -

Gathering of the Tribe: AcidVol 1 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £12.99

Gathering of the Tribe: AcidVol 1 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £12.99 -

Gathering of the Tribe: LandscapeVol 2 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £13.99

Gathering of the Tribe: LandscapeVol 2 — A practical guide to the ultimate occult record collection.£9.99 - £13.99 -

Gathering of the TribeAn album by album look at the role of the occult in popular music.£9.99 - £25.00

Gathering of the TribeAn album by album look at the role of the occult in popular music.£9.99 - £25.00

- Music

- Adrian Maben, Bob Dylan, D.A. Pennebaker, David Gilmour, David Kerekes, Dont Look Back, Gathering of the Tribe, Live at Pompeii, Mezzogiorno, Michael Wadleigh, Mick Farren, Naples, Nick Mason, Philip Wilkinson, Pink Floyd, Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Pompeii, Richard Wright, Roger Waters, San Francisco Fillmore Auditorium, Syd Barrett, The Dark Side Of The Moon, Woodstock

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress