Escape Into Sound – English Folk Music Via A Hole In The Floor

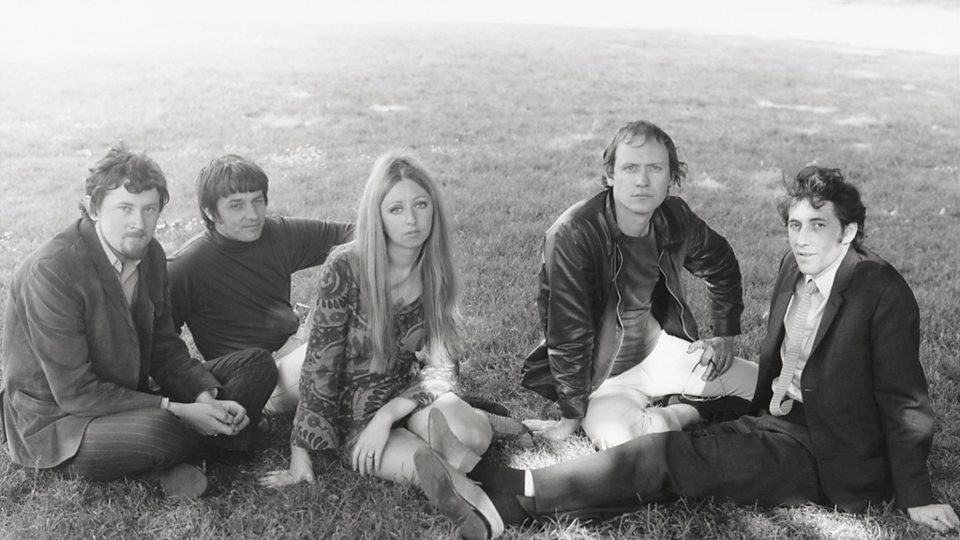

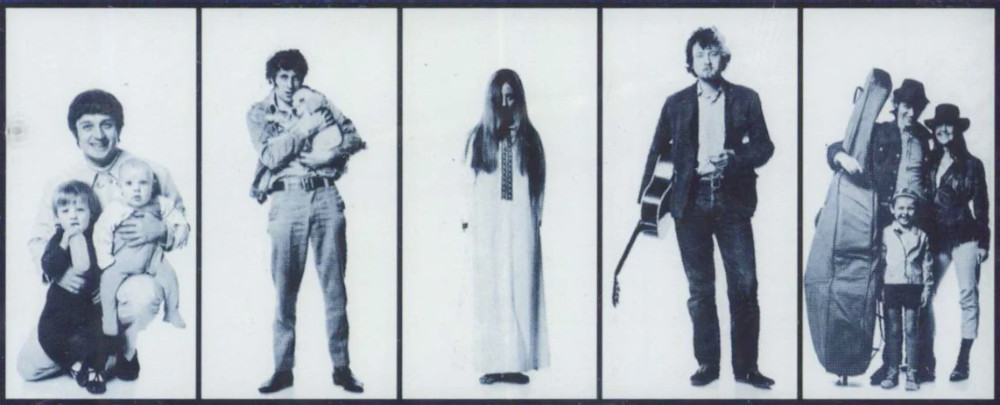

The Pentangle

Take Three Girls was a late 1960s BBC comedy drama that most people, if they remember it, tend to remember it for only one thing: the theme song. The opening track by Pentangle with its ethereal vocal and folky swing, was very different to the pop picks of the day, and, for this young viewer, catching episodes in the 1980s, a world of traditional folksong far removed from the rock and punk favoured by teenage rebels. Formed in London in 1967, Pentangle was a trapdoor to a different sound, literally — the first album of theirs I bought was not in a Virgin Megastore or John Menzies or Vibes in Bury but an early incarnation of the Paramount Book Exchange in Shudehill, Manchester, which, like many such shops in the 1970s and 1980s, also happened to be a nexus for inquisitive minds, brimming with fantasy fiction, zines, comics, French language books about torture, and smut. When part of the floor one day collapsed to reveal a hole underground, Paramount adopted the space to expand into used vinyl. A handwritten notice pinned to a wall read “Records” and on it a cheery musical notation plus an arrow that pointed down. Another sign warned us not to fall into the hole. The impromptu space was stale and afforded room for only one visitor at a time, via a rickety free-standing stepladder. A visit to the used vinyl department was a health and safety carpet ride, and here I found my first Pentangle album.

We might classify the band as folk rock, at a pinch acid folk, and importantly they had a glockenspiel before Mike Oldfield had a glockenspiel. Pentangle embrace two divergent aspects of folk, what A.L. Lloyd terms art music and folk music. The former is ‘a diversion for the educated classes’ and the latter ‘one of the most intimate, reassuring and embellishing possessions of the poor’.[i] Lloyd is not speaking specifically of Pentangle, but rather the English folk tradition, which, by 1967, when his book Folk Song in England was published, Lloyd considered a tradition rejected by the young. Interestingly, 1967 happened to be the year Pentangle formed and so we might rethink this rejection more in terms of a transformation. The band and its contemporaries, including The Incredible String Band and Fairport Convention, were a new deal, folk ballads and musical folklore amplified. There also appears to me a truism in this folk that rejects the troubadourism of Bob Dylan, and of protest songs with no meaning.[ii]

Members of Pentangle — Terry Cox, Bert Jansch, Jacqui McShee, John Renbourn and Danny Thompson — were disciplined in fields not exclusive to folk and this tugged at and propelled their music — as did booze and ego and a ‘strident American manager’.[iii] Jazz is an influence on Light Flight, the theme to Take Three Girls, and it’s likely no coincidence that the song, coupled with the title of the show on which it appeared, recalls Take Five, the cool jazz standard made famous by the Dave Brubeck Quartet.

Light Flight is an original composition that, like other original Pentangle compositions, including Train Song and Sovay, has the gist of timelessness, like it too might once have been performed in the courts of kings and queens. It was also a chart hit in the UK. Jacqui McShee’s angelic vocal is the most immediate aspect of the track, and arguably of the band, disquieting in its pureness. A riotous audience for a Pentangle reunion concert in Milan in 1982 falls silent when McShee sings solo.[iv] In a 2022 interview, the vocalist gives an amusing insight into recording the soundtrack for the film, The Ballad of Tam Lin (d: Roddy McDowall, 1971), changing her delivery when an American party in the control room said they were unable to understand her accent. McShee, in hindsight, considers the result more “like an elocution teacher, it was so clipped”.[v]

I had seen former members of Pentangle perform on separate occasions through the years (all in an art space in Bury, formerly the Derby Hall), including once when a novice technician switched on a smoke machine and induced a coughing fit in Jacqui McShee. She wasn’t happy. The original line-up in its entirety I saw at the Royal Festival Hall in 2011, unbeknownst to anyone a farewell concert weeks before the death of guitarist Bert Jansch. It was at this same venue, over forty prior, that half of Pentangle’s Sweet Child album had been recorded and, by happenstance, Sweet Child was the album I stumbled on in Paramount, the used bookshop in Manchester with the newly formed vinyl department down a hole in the floor.

Beyond the Axes of Influence

By some curious decree I find myself again underground with Pentangle, on a metaphorical other-worldly journey. And with Pentangle comes Davy Graham, another British folk ambassador, another magical being. My journey 150 miles to Exeter is for an altogether different reason — Sleaford Mods performing at the Lemon Grove — but beneath the cathedral city exist medieval passageways.

It is a cold day in November when I arrive.

Davy Graham’s tone is different to Pentangle’s; his music is playful, and Graham has great fun performing it. Not so much the case with Pentangle. The fun is here, sure, but the band — almost too perfect, their music too beautiful — conjures a sense of loss and longing, quantified in an equally paradoxical band name, the Pentangle, a five-pointed star within a circle, signifying life, connections and the five members of the original line-up.

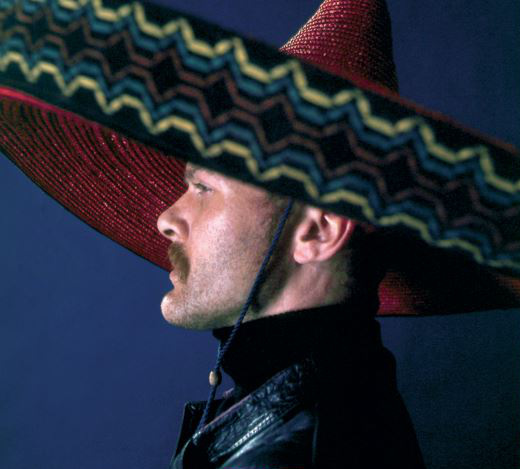

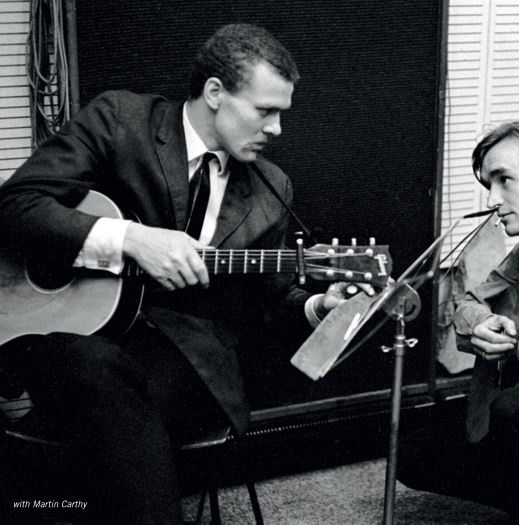

Graham is a recent addition to my library, having listened to Pentangle for years before my first encounter with his work. Indeed, it was in a book that I first made his acquaintance. The book, Singing from the Floor: A History of British Folk Clubs, I now cannot find but in it he most certainly is. Graham has the accolade of having invented the modern folk guitar, fusing a variety of styles with innovative tunings, some of them uncommon in the west when Graham adopted them. His influence is evident in the playing of contemporaries such as Bert Jansch and John Renbourn (both Pentangle), and acknowledged by a newer brood that includes Johnny Marr and Graham Coxon. Indeed, Jimmy Page in Led Zeppelin appeared to be waging a war of attrition on Graham, ramping up his finger picking to escape Graham’s velocity (White Summer is a fabulation of two Graham tracks: She Moves Through The Fair and Mustapha). And yet Graham, this godfather of British acoustic guitar, has become a detuned hero, absent beyond the axes of influence.

Unlike Pentangle, Graham didn’t carry so well into the 1970s. Distracted for a variety of reasons (substance abuse for a start), the drive for experimentation that marked his earlier work would diffuse his folk roots with a repertoire that included humorous songs, ragtime, covers of the Beatles and so forth. Sometimes it feels a bit like a BBC light programme, the audio equivalent of a more nourishing Fanny Craddock who is baking a cake.

Going underground

Vestiges of the long distant past persist in a bustling metropolis. Exeter is a town founded by the Romans circa AD50, and, like many small towns, a city wall once contained it. Bits of the wall now dagger the streets, something to avoid on the way to busy East Gate. Another aspect of Exeter’s past is the cathedral — in John Betjeman’s eyes, the most disappointing aspect — and, only recently opened to the public, the vaulted tunnels. Surviving disaster and calamity, no less plague and civil war, these tunnels are a hidden realm whose original purpose was to carry fresh water through lead pipes from beyond the city walls into the city. It is a unique attraction, with Exeter the only city in the UK to have underground passages of this type, according to the visitor website. The entrance is on Paris Street, off Main Street and from here down, down, down.

My stay in Exeter is brief, one night in a fifteenth-century coaching house rumoured to sport a variety of restless spirits, including a visitation from a lady climbing a missing staircase, as well as a malevolent creature of nonhuman provenance, and a child said to wander the corridors, a boy eternally lost.

From a fruit bowl at reception I take a complementary fresh orange. Everyone appears to have one, including those men embarking on a stag night, who talk horror stories concerning the coupling of a wedding ring with heavy machinery. I got tools at home. Lots of tools. Otherwise the coaching house appears empty.

My room on the first floor is numbered 101 — a trite if true metaphor for pending horror and the abstraction of love and fear. But the room, which is large, is also clean and I deposit my luggage and my fresh orange and leisurely head out to the medieval passages, for which I have a ticket. The wind is bracing and the shoppers that cling to the streets do so tightly. A dishevelled man jitters in a closed doorway, drunk or high, singing stoned at passersby. His aggressive rap inspires one of my own: “Your rhymes are shit, mate.”

Tales from the Crypt

I join a party of six, comprising students and lone travellers, and before the tour begins we wait in a room where a bank of lockers line one wall and safety hats another. We watch a brief film on the history of the passages and our guide, a greying man with sparky eyes, introduces himself for a health and safety preamble peppered with humour. Then we each take a hard hat from the wall and head together to the first tunnel.

Professor Robert MacFarlane observes that anything placed underground is almost always a strategy to shield it and that to ‘retrieve something from the underland almost always requires effortful work’.[vi] MacFarlane’s soundtrack at one point in his book, Underland: A Deep Time Journey, is The Jam’s Going Underground. Mine is not so obvious but effortful to retrieve, nonetheless, like all good things meant to last.

Our guide — I forget his name; Dan maybe — calls out at regular intervals to the last person in line to ensure he is present and by virtue of his reply we move on, snake-like, no one having become lost or panicked. The location of landmarks on the streets above us are identified, bringing a sense of proportion and progress through this underworld, the John Lewis, the Primark, the ghostly refrain of a busker and — our River Styx — what might be the chorus to Wonderwall. Now we are encouraged to feel the walls, the sedimentary rocks of different colour, cold and damp.

Our subterranean odyssey is remarkably like the opening scene of an Amicus horror film, one of those morality plays in which a small group of people become lost in a portmanteau to the afterlife, usually by way of a train carriage, or an asylum, or, as happens in Freddie Francis’ 1972 Tales from the Crypt, a catacomb. Soon, perhaps, we will confront a story that echoes a dream uncomfortably familiar to each of us. We have our own little Crypt Keeper, Dan the tour guide, sparky-eyed, engaging us in a manner not dissimilar to Sir Ralph Richardson. He reminds us in the low light to stay close and beware the low-lying pipes, which, to me, sounds a lot like death.

One of the group, a young woman wearing a snood, inquires about the age of the graffiti sunk into the near wall. These hieroglyphs are the initials of medieval tunnelmakers, comes the reply, children, because only children could traverse the tiny space in the construction of the passages. The woman lays a hand thoughtfully on the graffiti, a poet considering a stanza, and when she moves away I replace her hand with mine, as if to share in this parenthetical space — of Pentangle and Davy Graham and my hole in the floor shop, the salient ridge characteristics impressed upon time. Another member of the group, a large-footed man otherwise keeping much to himself, speaks next. He remarks upon the reinforcements, specifically the steel pipe stanchion installed above our heads, whose position, he says, speaking as a civil engineer, is contrary to a solid foundation. Instead, this is the weakest point of the tunnel and counter-intuitive to how things are done today. There are legends in all customs of sleepers in caves and people who come back to restore knowledge which is now lost. Dan the Crypt Keeper neither agrees nor disagrees, but his expression echoes concern over the blunt surveillance of the large-footed man.

I withdraw my hand from the wall, which feels wet like spit. Goin’ Down Slow by Davy Graham seems awkwardly prescient under the circumstances. Graham, part of a noble breed of artisans, is in good company with ancient graffiti, as he is the buskers overhead and the blind-drunk-rapper on Main Street who will soon ask where I have been. Civil engineer he is not. The wisdom of a professional hard-hat prevails because poems all told will not arrest a cave-in.

Both Sides Now

My own introduction to Graham, as noted, was late, and in some unfortunate respect in reverse, like Benjamin Button, having been beguiled by one of his decidedly off-piste cover versions. He conceded in a 1999 interview he had composed “only about twenty songs,” preferring to arrange and orchestrate.[vii] Joni Mitchell’s Both Sides Now is something of a standard but Graham’s version of it feels wrong, thunderous, too fast and pitched too high. However, while not exactly a likeable version, Both Sides Now is characteristic of Graham in that he makes something else of it. In the same interview Graham admits to his version sounding “strange really. I can’t think of one that sounds like it”.[viii]

Still going backward: a documentary on YouTube sees Graham pulled out of retirement for a live performance over two nights at the Edinburgh Festival, a few years before his death in 2008.[ix] Living free and high have evidently taken their toll and watching the stick-thin Graham play around on his guitar is a frustrating experience; while the fingers remain pliant they are missing the narrative, lost in a spiral of unwitting innovation. At one point, Bert Jansch joins the documentary for an impromptu performance, but the meeting of these two greats doesn’t really add up to much. Jansch is respectful and not a little frustrated by Graham’s inability to find a song and remain with it.[x]

Fifteenth Century Vibrations

My room in the fifteenth century coaching house is chilled on my return and remains so through the night, despite the radiator kicking out heat. I awake in the dark to a curious sound that at first appears musical. Rubbing sleep from my eyes, I deduce the noise isn’t a spectral hurdy-gurdy but something asthmatic outside the room and, try as I might, a sound I cannot ignore. Throwing on my clothes, I venture into the corridor, treading lightly while following the siren call to the stairs.

There is nothing quite like the corridors of a haunted coaching house when the lights are burning lonely. I wonder whether the ghost boy of legend, said to wander the building eternally lost, might once have been lured from his room the same way. Might I become lost like him, a sad and lonely figure for generations to come?

On the floor below I discover the source of the noise, entirely earthbound: an inflatable Santa slowly deflating. At the end of the corridor, surrounded by fairy lights, the larger than life Santa has a pump attached to a leg, a catheter automatically replenishing air each time the jolly smile sinks to a smirk beneath the jolly beard. I debate whether to unplug Santa and free the night of its phantoms. Ultimately, I leave him alone and return to bed.

The next morning, on my way to breakfast, I discover others were abroad last night and they were not so accommodating: Santa is dead, punctured, deflated, flattened by person or persons unknown. In reception a policeman talks with a member of staff and takes notes, the bowl of fresh oranges almost depleted. Why police, and why so soon to respond? The scene strikes me as the basis for an unlikely murder mystery, something clever like Martin Amis.

Ouroboros

During the walk beneath Exeter, in the medieval passages, I noticed tangents to the tunnels through which we were guided, other tunnels in other directions, inaccessible because they were either too small or unsafe. The mouth of one was near to the ground and inside — having bent down to investigate — a string of lights revealed a perfectly formed warren that stretched tantalisingly ahead, around a corner, and out of sight.

Now back in Oxford, leaving the rail station with a fresh orange uneaten, an encounter with a warren of a different sort: Botley Road bridge is closed to traffic because of ongoing construction work and pedestrians are required to circumvent the area via an impromptu passage of high-walled corrugated metal sheets. On either side of the walls are argon lights that illuminate an unseen area like Jurassic Park but populated by generators, grumbling at the night. Sometimes the high walls have been moved and the space is different, a zigzag this way as opposed to that. The strange ouroboros in which cyclists are required to dismount is now in its second year. No completion date exists, nor any sense of its purpose; the site simply serves the public passage, back and forth, and nothing more.

Noted earlier, A.L. Lloyd considered two forms of English folk music dictated by class. Another musician-author, Bob Stewart, his speciality folklore and faery tradition, agrees that folksong is often associated with ‘the bucolic and drink-sodden masses’[xi] but contests that, while easy to archive and catalogue as a body of work, folk songs themselves are not so clearly definable in content and meaning. The point Stewart makes I find interesting. Classic studies of magic and religion are often composed in a vacuum, he says, citing by way of example, George Frazer’s seminal The Golden Bough. He argues that ‘even the works of great scholars can only be exercises until they are related to human life.’

Davy Graham approaches music analytically, preferring to orchestrate and arrange. With Pentangle we might say the opposite, that the song is the magic expression. As with Lloyd, Stewart is not talking specifically about Pentangle, but in their work is the sense of lived-in experience, an emotional space that defies analytical convention.

Anything is possible with this haunting music, anything possible down a wobbly stepladder into an underworld that dictates the past. Travelling to Exeter via a hole in the floor you too may find yourself in a story unexpected, like this one, the fantastic paroxysms of Mr Benn’s costume shop, where links and connections are dictated by an escape into sound.

Notes

[i] A.L. Lloyd, Folk Song in England. Herts: Paladin, 1975 p.17

[ii] ‘To young blacks or the poor of any colour, he [Dylan] said not a word. In spite of his declared dislike of the bourgeoisie, his was a middle-class music.’ Tony Palmer quoted in Alan Sinfield, Literature, Politics and Culture in Postwar Britain. London & New York: Continuum, 2004, p.300

[iii] Jeanette Leach, Seasons They Change: The Story of Acid and Psychedelic Folk. London: Jawbone, 2010, p.87

[iv] Pentangle Reunions: Live & BBC Sessions 1982–2011, Cherry Red.

[v] Listening In: Jacqui McShee on The Ballad of Tam Lin (filmed and edited by Sarah Appleton, British Film Institute 2022) Included as an extra on the BFI blu-ray The Ballad of Tam Lin.

[vi] Robert MacFarlane, Underland: A Deep Time Journey. NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2019 (pp.11-12)

[vii] ‘Davy Graham interviewed 1999 by Pat Thomas in London,’ from the booklet included with Davy Graham: He Moved Through the Fair: The Complete 1960s Recordings, Cherry Tree, p.17

[viii] ‘Davy Graham interviewed 1999 by Pat Thomas in London,’ from the booklet included with Davy Graham: He Moved Through the Fair: The Complete 1960s Recordings, Cherry Tree, p.16 Also of note: Graham’s take on Both Sides Now is compiled on both He Moves Through the Fair and the Decca various artists collection, Psych! British Prog, Rock, Folk & Blues 1966–1973, where he shares company with another cover: Al Stewart’s fitful rendition of The Yardbirds’ Turn To Earth. The Yardbirds, a proto Led Zeppelin, once featured Jimmy Page in its line-up, and released songs outside of the R&B roots that defined them, evoking with Turn To Earth and also Heart Full Of Soul and For Your Love, pop music as a kind of electrified funeral violin.

[ix] Davy Graham & Bert Jansch: The Parting Glass, d: Don Coutts, 2005.

[x] The documentary is titled Davy Graham & Bert Jansch: The Parting Glass, although Jansch is only in it for a bit. https://youtu.be/WZ8oU5j-sSY?si=fT_TnMpx071ZipEk

[xi] Bob Stewart, Where is Saint George? Pagan Imagery in English Folksong. Wiltshire: Moonraker Press, 1977, p. 8

8 CD box set

Cherry Tree

- Music

- A.L. Lloyd, Amicus, Bert Jansch, Bob Dylan, Bob Stewart, Botley Road bridge, Bury, Danny Thompson, Dave Brubeck Quartet, David Kerekes, Davy Graham, Derby Hall, Exeter, Fairport Convention, Fanny Craddock, folk rock, Folk Song in England, George Frazer, Graham Coxon, Jacqui McShee, Jimmy Page, John Renbourn, Johnny Marr, Joni Mitchell, Led Zeppelin, Lemon Grove, Manchester, Martin Amis, medieval passageways, Mike Oldfield, Mr Benn, Oxford, Paramount Book Exchange, Robert MacFarlane, Roddy McDowall, Room 101, Royal Festival Hall, Singing from the Floor: A History of British Folk Clubs, Sir Ralph Richardson, Sleaford Mods, Take Three Girls, Tales from the Crypt, Terry Cox, The Ballad of Tam Lin, The Golden Bough, The Incredible String Band, The Jam, The Pentangle, Underland: A Deep Time Journey

David Kerekes

Like this article?

Related Posts

Comments

Copyright © Headpress